Featured in the exhibition "Portraits and Other Likenesses," currently on view at the Museum of the African Diaspora: "Sista Sista Lady Blue," 2007, by Mickalene Thomas; chromogenic print, 40 3/8 x 48 1/2 in. Collection SFMOMA, © Mickalene Thomas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel

The verb "curate" no longer assumes an art world context because these days nearly everything we experience purports to be curated, especially online. In fact the word no longer assumes a person who curates, since algorithms make so many choices for us.

Whether human or virtual, the act of selecting something and serving it up can miss an essential element of the word's original meaning. Curate derives from the Latin cura, to care.

Some 35 years into a distinguished career as a curator, 24 as an independent curator, Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins still cares. She has lost none of the excitement and wonder with which she first encounters a work of art and seeks to understand, interpret, and share it. It may well have to do with the fact that, in addition to being an art historian (with a Ph.D. from UCLA), she is an artist herself.

I interviewed LeFalle-Collins at the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco shortly before before the opening of Portraits and Other Likenesses from SFMOMA, which she co-curated with Caitlin Haskell, assistant curator of painting and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Continuing through October 11, the exhibition features 48 works by artists from the African Diaspora and Latin America who have explored issues of identity through African, European, and American visual-cultural forms.

LeFalle-Collins has a notable legacy of bringing attention to important artists before others discover them, like assemblage artist Noah Purifoy, and to neglected or forgotten ones, like P.H. Polk, the official photographer for Tuskegee University. She organized Purifoy's first solo exhibition, with a catalogue and tour in 1997, while staff curator of visual arts for the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, and also developed a collection strategy for LA's Black assemblage artists' works from the 1960s. She met Polk in his 80s, in 1979, and over the next five years visited and consulted with him about organizing his photographs which were strewn into wooden bins throughout his shop. She has also exhibited and written about the work of David Hammons, Mildred Howard, John Outterbridge, and Betye Saar (showcasing Outterbridge and Saar in two international biennales), among many others.

"I tell artists all the time," says LeFalle-Collins, "You have to be written about." And it's been her personal mission as a socially and politically engaged curator to expose artists of color to as broad an audience as possible through her writing and museum work.

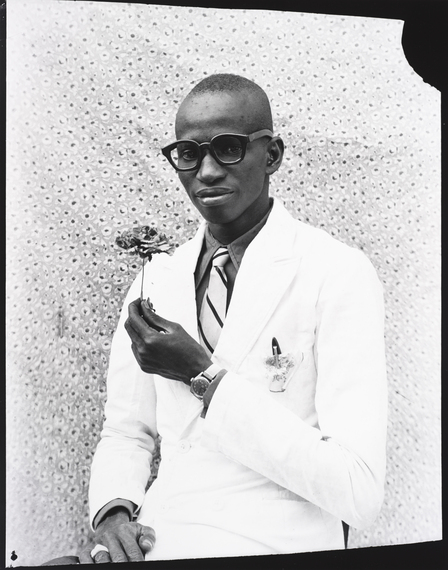

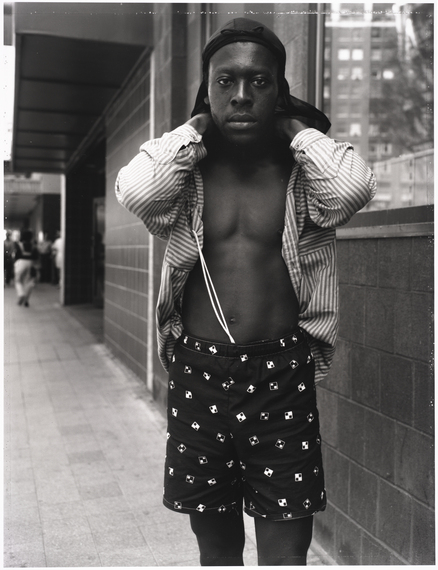

Dawoud Bey, "A Young Man in a Bandana and Swimming Trunks, Rochester, New York," 1989; gelatin silver print, 24 x 19 1/2 in. Collection SFMOMA, © Dawoud Bey

To be among the first to recognize and articulate an artist's significance leaves an indelible mark not only on a curator's career, but on many people's lives--from the individual artist and their larger community, to everyone who will ever discover and be moved by that work, even after its creator is gone.

The curator, in caring, makes us care too.

For the MoAD show, LeFalle-Collins took an expanded view of portraiture's forms and meanings for artists who creatively deploy fiction, subversion, stereotype and fantasy as they grapple with issues of representation in painting, sculpture, photography, and media art. All the works are drawn from SFMOMA, more than half of them new acquisitions exhibited for the first time as part of that museum's collection. In addition to recommending pieces for inclusion in the show, LeFalle-Collins developed its conceptual framework and title.

Works on view include Nicole Miller's 2011 video portrait of Cornel West, which San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker calls a "standout" that "stretches the bounds of portraiture in a new and timely way."

Miller's piece is an example of the "call and response" thread central to the LeFalle's concept for the show: It's a digital collage--a mashup YouTube clips on a computer screen--that harkens back to Romare Bearden's 1960s paper collage work Three Men (1966-67), also featured in the exhibition.

Romare Bearden, "Three Men," 1966-67; printed and painted papers, watercolor, and graphite on canvas, 57 1/2 x 41 5/8 in. Collection SFMOMA, © Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel

"Whole college courses might be devised to study topical cross-sections of the exhibition," adds Baker, "and with any luck, some will be."

Anton Stuebner's review for Art Practical effectively frames some of the complicated terrain such a course might cover:

"[P]ortraiture bears its own troubled relationship to genealogies of violence and erasure that excluded nonwhite bodies from representation in Western art. By asking their audience to consider what 'makes' a portrait, the show's curators...provoke far more trenchant questions about race and subjectivity. How do you define your identity when your physical likeness has been culturally othered? And how do you engage with representational traditions that have historically denied people of color?"

As I walked with LeFalle-Collins through galleries spanning two floors of MoAD, dozens of art works were in various stages of installation, half uncrated or leaning against walls, in multivalent conversation with each other. British artist Chris Ofili's towering 8-foot-tall canvas, Princess of the Posse (1999), sparkled darkly with acrylic, glitter and elephant dung, while Glenn Ligon's series of smaller framed prints, a self-portrait in the form of frontispieces to fictional slave narratives, spoke quietly of his identity as "a colored man, who at a tender age discovered his affection for the bodies of other men, and has endured scorn and tribulations ever since...."

The Portraits exhibition is a capstone of sorts for LeFalle-Collins' career as a freelance curator. While she will continue to serve in a consulting capacity to museums, arts organizations and artists, she will champion artists' work in new ways through LeFalle/Collins Projects, a traveling exhibition service launched in partnership with her son and her husband--taking art places it's never been before, hand in hand with the next generation.

Sargent Johnson, "Forever Free," 1933; wood and paint, 36 x 11 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. Collection SFMOMA, © Estate of Sargent Johnson. Photo: Don Ross

You've curated for both SFMOMA and MoAD, so you personally are a kind of bridge for this show.

Yes, I curated an exhibition at SFMOMA in 1996 on Sargent Claude Johnson, who was the subject of my Ph.D. dissertation. And for MoAD I organized the two 2005 inaugural exhibitions. I've had a long relationship with both museums.

I know that SFMOMA's construction closure during its expansion provided the opportunity for off-site programming including this collaboration with MoAD. But what was the seed for the exhibition's focus on portraiture?

When we first talked about the show on African and black diaspora artists I said [to SFMOMA], "Let me see what you have." So they sent me things that were available, and I looked at all of them, possibilities for this exhibition, and tried to find threads. I thought about portraiture--and I knew I wasn't dealing with traditional portraits, that I was looking at portraiture in another way, that spoke to how one identified oneself, how one thought about family, culture, those kinds of things. I am a curator who believes that there are many stories to be told and many ways of interpreting art. I like broad definitions. I like other things to sneak in. So people aren't bound to think about things just one way, that there are other possibilities.

David Hammons, "Putting on Sunday Manners," 1990; inner tube, chair back, flipper, tennis ball, nails, and wire, 32 x 24 x 16 1/2 in. Collection SFMOMA, © David Hammons. Photo: Ben Blackwell

You were working with familiar artists but with a fresh curatorial eye.

Yes. When I got the list of artists and images from SFMOMA I was surprised--we were talking about the same artists that I had shown before and some that I had written about. It was really full circle--curating works by Yinka Shonibare, Robert Colescott, Adrian Piper, Kara Walker, Lorna Simpson, Malick Sidibé. But because this is my last show, I wanted to take more chances. My choices could be more complicated, more provocative. As new works were acquired for SFMOMA's collection, I researched the artists' images, the stories behind the works, and the "portraits" that emerged. I was delighted to push further and include artists who I hadn't curated into exhibitions before like Nicole Miller, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Jaoquin Trujillo, David Huffman and Jack Witten. It became a performance for me--I assembled the artists' works together into a great collage as I decided to examine "What is a portrait?" That's the question. Once we decided that, we had a lot more to look at--portraits of a different kind, a more broad definition. We say [reading from her notes]: "Not every piece on view is a portrait in the traditional sense. Most could be characterized as pictures of people. Some are visual depictions of recognizable individuals, while others are literary or symbolic descriptions--idealizing, abstract, ironic--that remind us of the many ways that inhabitants of the world can become inhabitants of images."

That's so true, the notion of "becoming inhabitants of images." The fact that representations of people of the African diaspora, at least in popular culture and in the media, are mostly not of their own making.

Yes, it's very limited. We really opened things up. It can be challenging for some people, but it can also be very engaging--for example, Nicole Miller and Nick Cave's work being read as portraits. These artists are saying, "If you want to take the time, this is who I am, this is who we are."

Lorna Simpson, "Necklines," 1989; gelatin silver prints and engraved plastic plaques, 68 1/2 x 70 in. Collection SFMOMA, © Lorna Simpson

Why did you decide to start in the 1920s?

I was thinking of the whole idea of call and response--not just with African American but with African traditions. So I thought of these older artists and these older images in SFMOMA's collection, and how in many ways they connected with some of the present-day artists, how they're looking at some of the same issues, but their imagery is different.

You had not expected that?

No, I wasn't looking for that. The work told me that. And I always think that the work should speak to you. What's in front of you should speak to you. At the time I didn't know a lot of the background of the pieces. I was drawn to them because of what was in front of me. The artist's voice is really primary.

And the curator is a listener.

Yes. So I looked for their words. I wanted to find out what the artists were saying about these works. I was surprised at what I found because there are all these back stories that I didn't even know were there. A lot of these artists have given interviews, and ones who've died who talked about their works prior to their death--on Van der Zee, for example, there's a lot of information, but P.H. Polk, no. I've been reflecting on this lately, my path as a curator, and I went back to my first museum experience at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, working as a volunteer in the registrar's office while I was in graduate school at the University of California, Santa Barbara. From there I went to Tuskegee University, where my husband got a job, so we picked up and moved to the South. We got there just as this large collection had to be moved out of the George Washington Carver Museum. It was a real opportunity to use my skills from SBMA to document the collection during its move.

Consuelo Kanaga, "Annie Mae Meriwether," 1935; gelatin silver print, 13 x 10 1/8 in. (33.02 x 25.72 cm); Collection SFMOMA, gift of Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein; © Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

I imagine that was an especially great opportunity since you were still new to curating.

I had an MFA in painting and drawing. I wasn't thinking anything about art history and curating. But I had to pull it all together. There were some fabulous pieces in that collection--19th century pieces that I only knew because of the books Two Centuries of Black American Art by David Driskell, from the 1976 exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Art: African American by Samella Lewis, from 1978. I said, "Wow, I am right here with these."

I appreciate that sense of wonder: I am right here with these. It's a feeling I have too, in museums and archives. I think what you capture in saying that is what an intimate, even sacred, relationship one can have with art.

In my curatorial practice it's that direct relationship with art and artists that is most important to me. And I hope in the future we will see these works that are now in the Portraits show in diverse contexts too, beyond culturally or racially specific, but alongside other work. That's the whole idea, to view them as part of the art historical canon. In the end, my story as a curator is tied to the contributions I've made in expanding historical and cultural discourse on the work of U.S. Black artists in the midst of challenges within and outside of the museums and arts organizations I have worked for. Although I have had a long and fulfilling career, I am mindful of the challenges, resistance, and choices that all artists and curators of color face. You do what you can in a tightly controlled and limited space.