Christine Bennett remembers her childhood days in Mossville, La., walking to and from school through an alley of industrial plants.

"We had to cup our noses just to breathe," said Bennett, who for 53 years lived in the southwestern Louisiana town, a longstanding African-American community.

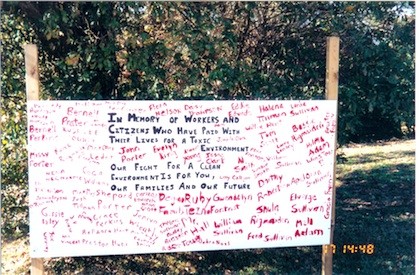

Bennett, along with other community members and environmental advocates, is now fighting to protect future generations from having to breathe what she considers hazardous air. The community activists are pushing the government to set more stringent pollution standards for some 12 nearby industrial facilities.

Their latest battle concerns the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's new rules for polyvinyl chloride plants. These plants are considered extremely dirty by environmental advocates; the EPA estimates that U.S. PVC plants collectively emit more than 1,400 tons of hazardous air pollutants each year.

The EPA's recently finalized standards impose weaker emission standards for a Mossville PVC-producing plant and a Houston area plant than for 15 similar facilities around the country.

"For reasons mystifying to us, the EPA singled out these two communities for weak standards, including this one community we were really trying to help," said Jim Pew, a staff attorney for the nonprofit Earthjustice, which has raised awareness of environmental justice concerns in Mossville.

On Tuesday, Earthjustice filed a lawsuit and a petition on behalf of Mossville Environmental Action Now, the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Air Alliance Houston and the Sierra Club, asking the EPA to reconsider its final rules. They contend that the agency's decision represents a reversal of its original plan, which called for both facilities to follow the same regulations as other PVC plants.

The two plants fall under a different category than the other PVC plants, the EPA stated in April 2011, noting that it would still regulate them in the same fashion. Yet in new rules issued on April 17 of this year, the two plants were listed as having to meet less stringent emissions standards. But Pew argued that all 17 PVC plants create "the same product and the same emissions."

"Layer that onto the fact that both communities are environmental justice communities," he said, noting that Mossville receives toxic fumes from the area's numerous industrial facilities and has a network of underground and elevated pipelines that carry hazardous materials. "Mossville especially has just been on the receiving end of one horror after another."

The petition, addressed to Lisa Jackson, the first African-American to serve as the EPA's administrator, challenges what it calls the agency's weak standards and failure to consider environmental justice concerns as "unlawful, arbitrary and capricious."

When asked about the materials filed by the environmental groups this week, the EPA released a statement that it "will review the lawsuit and respond accordingly."

CertainTeed Corp.'s PVC plant in Mossville emits every year an estimated 19 tons of hazardous air pollutants, including vinyl chloride, benzene and dioxins (all human carcinogens), according to Earthjustice. Like other PVC plants, the facility also spews probable human carcinogens such as acetaldehyde and formaldehyde, the organization claims.

A federal survey done in 1999, and repeated in 2006, found that the average resident of Mossville carried three times the concentration of dioxins in the blood as a typical American. Researchers also discovered dangerous levels of dioxins in fish. Other studies, by Mossville Environmental Action Now, have found dioxins in indoor dust and yard soil where children of Mossville play.

Russ Hauser, an environmental health professor at the Harvard School of Public Health, noted that dioxin exposure can increase the risk of medical problems, including, among others, cancers, diabetes, endometriosis, decreased semen quality -- conditions that many Mossville area residents currently have.

"The list of health concerns is quite long," said Hauser, who has studied the effects of dioxins on Russian children.

Under the originally proposed standards, hazardous air pollutants including dioxins emitted form the Mossville plant would have been reduced by about 87 percent, noted the petitioners. The Houston area plant, which sits across a highway from three schools, neighborhoods and churches, would have been forced to lower emissions from about 82 tons to 53 tons each year.

Now the combined pollution reduction required for the two plants is expected to be less than half of that initially proposed by the EPA.

For some hazardous air pollutants, the rules have changed dramatically: CertainTeed's allowed emissions for vinyl chloride is now more than 15 times higher than what had been initially proposed.

Environmental advocates also argue that the guidelines should be drawn up for PVC plants in Mossville not in isolation but while considering all the community's polluting facilities, which include an oil refinery, coal-fired power plants and the country's largest concentration of vinyl manufacturing facilities.

"Nobody is really asking the right questions in terms of protecting this community," said Earthjustice's Pew. "Rather than looking at each piece by itself, we should be looking at it holistically."

Hauser agreed, noting that multiple exposures can add up or even interact to cause more harm.

"Pollution is raining down right and left in this community," added Monique Harden, codirector and attorney for Advocates for Environmental Human Rights in New Orleans. She expressed disappointment with the EPA's decision, especially "given the administration's commitment to prioritize environmental justice," she said.

The EPA's new Plan EJ 2014, for example, aims to protect health in communities burdened by pollution and specifically acknowledges that socioeconomic disparities can increase an individual's vulnerability to toxic air pollution.

But the loosened regulations set for Mossville's PVC plant are not unprecedented.

Seven years ago, after finding “no legal remedies” within the United States to address the flaws in environmental protection, Harden's group helped Mossville community members file a human rights petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Advocates won a hearing on behalf of the residents in 2010, marking the first time the organization would hear complaints of environmental racism against the United States by its own citizens. The case is still pending.

The EPA's latest move bolsters the community's claims, Harden suggested. Mossville is seeking help with health care and relocation for burdened residents, as well as environmental restoration and regulatory reform.

"This was once a wonderful, thriving, beautiful community, where people could live well," Harden said. "But the way these industrial facilities operate, there is a complete disregard for human life."

Bennett, the lifelong Mossville resident, lives with a host of health issues. She is more concerned, however, about Mossville's future generations. Her niece, Jasmine, recently underwent surgery for cancer in her right cheek. "Imagine coming up in this world with your face disfigured," said Bennett. "She has to live with this the rest of her life. She can't afford plastic surgery."

Today, Mossville area schools rank in the top 2 percent of U.S. schools with the worst air, according to USA Today.

"We breathe every day," said Dorothy Felix of Mossville Environmental Action Now. "And what we breathe is not good."

"We are an African-American community. They prey on communities like this," Felix added. "But we are going to continue to fight until they hear our voices and until justice is served."