WASHINGTON -- Charity is at once a virtue, a wedge, a symbol and a prism. For those who believe in limited government, charity is the answer to the riddle at the heart of free-market conservatism: What about the poor? The needy? The ones left behind?

The Huffington Post examined each of the contenders for the White House through the lens of their charitable efforts. A close look reveals telling patterns.

The 2012 Republican candidates for president have a mixed record of charitable giving. Little is known about Michele Bachmann, Ron Paul or Rick Santorum, due to a dearth of public records and campaign disclosures. Texas Gov. Rick Perry released his income tax returns, which reveal that his donations to charity rose in tandem with his political influence. Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich both spent years building large private foundations to advance their charitable and political goals. Herman Cain, on the other hand, refuses to blend politics with charity. Last, there is Jon Huntsman, Jr., the son of a great philanthropist, for whom friends say the approach to charity never wavers amid the ups and downs of politics.

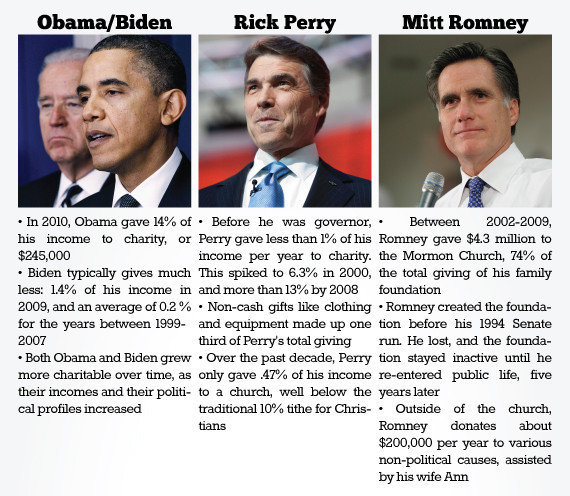

On the Democratic side, President Obama and Vice President Biden have each publicly disclosed 10 years' worth of income tax returns, which reveal a surprising disparity between the two men.

There's an old stereotype about charity and politics that conservative voters are less concerned with whether or not politicians donate to charity than liberals. Yet a robust, private charity is central to the conservative world view, which means that charitable giving may end up being more important to Republicans.

A comprehensive 2008 study revealed that participants who identified as conservatives reported giving significantly more of their average household incomes to charity than participants who identified as liberals. For progressives, society is made better by the collective action of a democratic people, expressed through their government. For conservatives, social ills ought to be relieved not by government, but by individuals acting on their own or through private charities. It stands to reason, then, that Republicans would naturally display more interest in the 2012 candidates' charitable giving records than Democrats. They are also more likely to place a premium on candidates with strong records of giving to charity.

Obama/Biden: Night and day on charity

The current White House is a case study in contrasts when it comes to charitable giving. President and First Lady Obama have shown an impressive commitment to philanthropy, giving increasingly more as their income has risen. But the increase in giving has also corresponded with political ascent, bringing far more scrutiny of their personal finances. Nonetheless, in 2010 the Obamas gave $245,000 to charity -- roughly 14 percent of their $1.7 million income. In each of the previous three years they gave about 6 percent. This rose from $2,350 in charitable donations made in 2000, or about one percent of their $240,000 income that year.

Vice President Biden and his wife, Dr. Jill Biden, on the other hand, have given very little to charity, at least as reflected in their tax returns. From 1999 to 2007, the Bidens declared just 0.2 percent of their income as charitable donations. That percentage didn’t climb above one percent until 2009, when they gave $4,820 out of $333,000 in income, or 1.4 percent.

These figures place Biden and his wife well below the national giving average. According to a report by GivingUSA, total estimated charitable giving in America in 2010 was 2.0 percent of the nation's Gross Domestic Product. Experts prefer this measurement over individual income statistics because it factors in broader economic conditions, such as the Great Recession.

Compared to that baseline, most of the Republican candidates for president fare reasonably well.

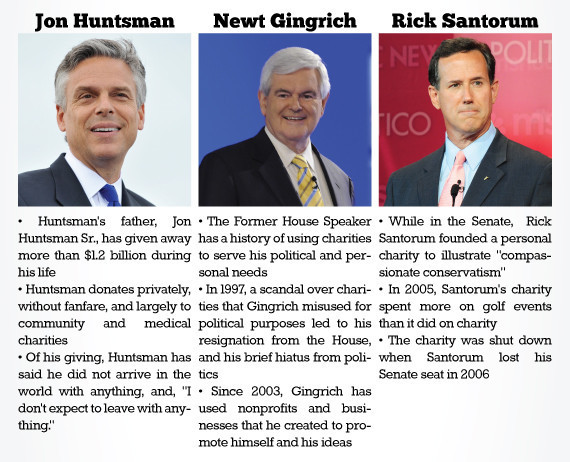

Perry's influence, generosity grew in tandem

The only GOP candidate who has released his income tax returns is Gov. Perry, which is ironic given his reputation for secrecy. Texas law, however, requires that the governor make his or her tax returns public, and Perry has complied by disclosing his filings dating back to 1996.

Like Obama, Perry's charitable donations increased alongside his financial and political fortunes. Perry served as Texas’ lieutenant governor from 1999 to 2000, when he replaced George W. Bush, who had just been elected president. For the five years on record before that, Perry never gave more than one percent of his income to charity, just like Biden. In 2000, Perry made only $646 in charitable donations, out of $137,000 in income, or roughly 0.4 percent.

In 2001, Perry's first full year as governor, his charitable giving spiked to 6.3 percent, or $9,150 from an income of $146,000. Charitable donations from Perry and his wife, Anita, have fluctuated since then, and their tax returns have only been disclosed through 2008. Nevertheless, from 2001 to 2008 their charitable donations averaged 4.4 percent of their income every year.

But there is one significant caveat. Of the $97,864 that the Perrys gave to charity between 2001 to 2008, nearly a third of that total -- $30,518 -- was in the form of non-cash gifts, which are known as "in-kind" donations in the charity world. Most of these in-kind gifts consisted of clothes, housewares, sports equipment and other items intended for nonprofit groups. Their value was determined by the Perrys, a standard practice with in-kind donations. If these in-kind gifts are subtracted from their eight-year giving total, records show the Perrys donated around 3 percent of their yearly income.

(Perry, cont.) Two years in particular stand out as especially generous. In 2005, the couple donated $23,063 to charity, or 12 percent of their $190,000 income. In 2008, that percentage rose even higher, to 13.6 percent, or $37,986 of $278,000 in income. And while the 2005 total included $6,235 of in-kind donations, in 2008 the Perrys gave all cash. More than a quarter of that money, $9,995 to be precise, went to an organization where Anita Perry worked as a fundraiser -- the Texas Association Against Sexual Assault. The group provides counseling services to assault victims and education programs for women. Records show that it paid Mrs. Perry $64,000 in salary during 2008.

By contrast, the biggest off-year since Perry became governor was 2007, when the family donated only $4,458 to charity -- nearly all of it, $4,045, as in-kind donations. This was the same year that Perry's income topped $1 million for the first time, most of it as the result of selling a lakefront property. The Perry family's charitable gifts that year amounted to less than half of one percent of their total household income, and the governor took a beating in the press -- one that was certainly on his mind the next year, which was his most generous year on record.

Despite the significant increase in his charitable donations, there is one area in which Perry's charity falls short of what voters might expect of him, especially given the prominent role Christian faith plays in his personal political narrative. During the past ten years, the Perrys have donated only 0.47 percent of their total income to churches, or $12,668. That's 20 times less than the traditional tithe of 10 percent that strict Christians historically donated to their house of worship each year. Asked about the discrepancy, a Perry spokeswoman told the San Antonio Express News, "tithing is only one aspect of a person's faith."

Romney: More charitable in the spotlight?

While Perry's lackluster tithing comprises "only one aspect of his faith," this happens to be an aspect where his chief rival, Mitt Romney, excels. A successful private equity investor and a practicing Mormon, Romney and his wife, Ann, donated more than $4.3 million to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS) between 2002 and 2009, according to an examination by The Huffington Post. The gifts were made through the family's private entity, the Tyler Charitable Foundation, and represented 74 percent of the foundation's total outlay during that period. Romney has yet to release his individual tax returns, so it's impossible to calculate exactly what percentage of his income the LDS Church received in a given year, but 10 percent tithes are considered a minimum gift in the Mormon tradition -- a convention strictly enforced by cultural norms.

Much like with the Obamas, the trajectory of the Romney family's giving tracked neatly with the man of the house's political rise. The foundation was initially named the Ann D. and Mitt Romney Charitable Foundation, and was created in 1993 as Mitt Romney prepared to enter politics for the first time by challenging the late Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.). Following Romney's defeat in November of '94, the foundation languished, devoid of funding while Romney returned to work at Bain Capital. By the beginning of 1999, the foundation's total assets were listed as $0 in IRS filings.

As Romney prepared to take over the Salt Lake City Olympics, he and his wife renamed the foundation and injected more than $3.6 million in high-tech stocks into it. For the next two years, the reincarnated Tyler Charitable Foundation supported just three organizations -- all Mormon and all based in Utah. The foundation only began donating to non-Mormon groups in 2002, when Romney's gubernatorial campaign brought the family back to Massachusetts. That year, the foundation supported a broad range of Massachusetts-based groups, including the New England Center for Homeless Veterans and the Boys and Girls Club of Boston.

Romney's secular donations since then have averaged about $200,000 per year, in relatively small increments and spread out primarily over programs addressing health, education and at-risk youth. He also donated the $127,000 in proceeds from his 2010 book, "No Apology: The Case for American Greatness," splitting the profits among seven organizations devoted to children and health-related issues.

Romney's giving benefits from the participation of his wife, Ann, whose 1998 diagnosis of MS sparked family donations of more than $100,000 to fund medical research on the disease, as well as cancer, HIV and Lou Gehrig's disease. A mother of five, Mrs. Romney has donated her time as a board member to the United Way and to the New England Chapter of the MS Society.

Lots of gifts, little fanfare for Huntsman

Mitt Romney may not be most generous Mormon in the presidential field. His Utah-based counterpart, Jon Huntsman, Jr., has been learning how to give charitably since his father struck it rich in the chemical business. Jon Huntsman, Sr., did not start out wealthy, but since he became a billionaire he's set an example for his son and society as one of the nation's most generous philanthropists. At 74, the elder Huntsman has given away a reported $1.2 billion during his life.

The fact that so few people knew of Huntsman Sr. before his son ran for president -- and so few still know of him -- is a reflection of the family's brand of low-key, local charity. It also helps to explain why there is such a scant record of Huntsman Jr's. donations.

(Huntsman, cont.) To date, Huntsman Jr. has disclosed only the most basic information about net worth required by the Federal Election Commission, reporting that he is worth between $15 million and $66 million. While a wealthy man by any standards, he has yet to create his own family foundation like Gingrich and Romney have. The relative lack of donation records makes it impossible to consider Huntsman Jr.'s charitable activities in relation to his political ascension.

As the favored son of a billionaire, Huntsman Jr. had opportunities available only to the privileged few. But he has also distinguished himself throughout his career, which began as a staff assistant in the Reagan White House. President George H. W. Bush later appointed Huntsman as U.S. Ambassador to Singapore at 28, making him the youngest American ambassador in more than a century.

Today the bulk of Huntsman Jr.'s charitable expenditures go toward supporting nonprofits founded by his wife, Mary Kaye. The largest of these is the Power in You program, which aims to empower at-risk adolescent girls with positive messages. The second group is the Bags of Hope campaign, which provides bags filled with games, snacks, books and a teddy bear to children diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes. For Mary Kaye, this is a personal endeavor -- the couple's daughter Liddy was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes in 1997. In addition to these groups, Huntsman's campaign disclosed that he has recently donated to the LDS Church, the Washington National Cathedral, two Utah homeless shelters and the orphanages where his family adopted their two youngest daughters, Asha Huntsman and Gracie Mai Huntsman.

Yet somehow this laundry list of recipients fails to capture the purpose or scope of Huntsman's personal charity, according to friends and nonprofit executives who spoke to HuffPost. These interviews conveyed a sense of Jon and Mary Kaye Huntsman as two people on a quest to return the good fortune they have been given.

"We didn’t come into this world with anything, and [I] don’t expect to leave with anything," Hunstman Jr. said during a June radio interview. "If the good Lord gives you something along the way ... then it’s our philosophy that you turn around and plow it back in and try to make people’s lives a little bit better," he said.

For Huntsman, charitable giving is private and selfless. For Newt Gingrich, it appears just the opposite.

Gingrich's favorite charity: Newt Gingrich

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich's 30-year career in Washington is peppered with the names of tax-exempt charitable groups he has used to further his legislative goals, business interests and personal ambitions. His actions, it seems, adhered to the letter of the law. Beyond that it gets a little murky.

WATCH: Gingrich rails against giving people something for nothing.

In 1997, a four year investigation by the House Ethics Committee found that Gingrich created and oversaw a network of six charitable organizations designed to benefit GOPAC, the Republican political action committee that he chaired. Between 1985 and 1995, these small charities collected more than $6 million in tax-deductible donations and funneled them to Republican causes, primarily GOPAC. Federal law prohibits tax-exempt charitable groups from engaging in partisan political efforts, which includes supporting one candidate to the exclusion of others. To get around this, the groups masked their partisan agenda under a cloak of bipartisan rhetoric.

The scheme ultimately cost Gingrich his position as Speaker of the House and his seat in Congress, but not before it helped boost Republicans to a historic majority in 1994's "Republican Revolution," and catapulted Gingrich to the nation's third-highest office. Gingrich resigned from the House in 1998 following a formal reprimand, and paid a $300,000 fine for the costs of the investigation. Gingrich's re-entry into the politico-charitable world is all the more bizarre given the consequences that mingling the two had for him last time around.

Much as with Romney, Gingrich's charitable endeavors all but disappeared when he stepped away from politics in 1998. He has yet to release his tax returns, and a search of IRS filings and public data came up blank for the next five years.

It wasn't until 2003 that Gingrich found a second act on the political stage. Over the next six years, he founded four new tax-exempt groups: the Gingrich Foundation, Renewing American Leadership (ReAL), American Solutions for Winning the Future and ReAL ACT. He also started three new companies: Gingrich Productions, Gingrich Communications and Gingrich Holdings.

Today, the companies and charities Gingrich created make up a nebulous, interconnected web, where the various entities serve each other and they all ultimately Gingrich.

Of the four nonprofits, the Gingrich Foundation is the oldest, dating back to 2003, and it is largely controlled by his wife, Callista Gingrich, who serves as its president. IRS records reveal that the foundation donates mostly to arts and education. The remaining three groups are significantly more political, and there are strong indications that they serve as little more than vehicles for Gingrich's self-promotion.

(Gingrich, cont.) Founded in 2007, American Solutions was a 527 tax-exempt advocacy group created to spread Gingrich's ideas. For four years, it was one of the most successful issues PACs in the country, raising more than $52 million from thousands of donors.

As with the rest of his projects, Gingrich was the star of American Solutions, and the group spent lavishly on private jets so that he could travel the country. It also helped to boost sales of the 23 books he has written and the eight documentaries he has produced with Callista.

But when Gingrich announced his candidacy this spring, he was forced to sever ties to American Solutions. Without Gingrich at the helm, American Solutions quickly withered and closed its doors, ultimately going bankrupt in August.

The third tax-exempt group, Renewing American Leadership (ReAL), was created in 2009 as a 501c(3) charity, aimed at "defending and promoting the three pillars of American civilization: freedom, faith and free markets." Gingrich also created ReAL Act, a Political Action Committee with the same goals as the charity, and during the first year ReAL and ReAL Act existed, Gingrich's personal spokesman, Rick Tyler, served as director of both groups.

During the next three years, ReAL raised millions of dollars through direct mailings written on Gingrich's letterhead, asking for donations to protect America's Christian heritage from President Obama. According to IRS records, the charity spent most of the money it collected to pay for more mailings. It also provided Gingrich with the names and addresses of everyone who responded -- an extremely valuable commodity to a politician.

In June, a scene reminiscent of Gingrich's House years played out when ABC News revealed that ReAL paid $220,000 to Gingrich Communications. This was purportedly to cover the cost of Tyler's salary and to buy Gingrich's books and DVDs. Tyler was one of nearly a dozen members of Gingrich's staff who quit en masse in early June.

Gingrich has so far refused to comment on the charity payments.

More golfing than good deeds for Santorum

Like Gingrich, Rick Santorum learned the danger of mixing charity and politics in 2006, when the nonprofit he founded came under fire for its close connections to his political operation. Then the junior senator from Pennsylvania, Santorum had founded Operation Good Neighbor in 2000 to support social services groups and "illustrate compassionate conservatism," according to forms filed with the IRS.

But an investigation revealed that Santorum used a disproportionate amount of the foundation's funds on golf outings and unexplained travel. In 2005 alone, the group spent more than $118,000 on three golfing fundraisers. The events cost the group more than they raised -- nearly $50,000 more, according to IRS records. Operation Good Neighbor was further beset by revelations that it was run by Santorum's campaign staffers, most notably lobbyist Barbara Bonfiglio, who served as treasurer of Santorum PAC America's Freedom, his 2006 re-election campaign and the charity. Santorum lost his 2006 re-election bid, and as with Romney and Gingrich, his charity went the way of his political career.

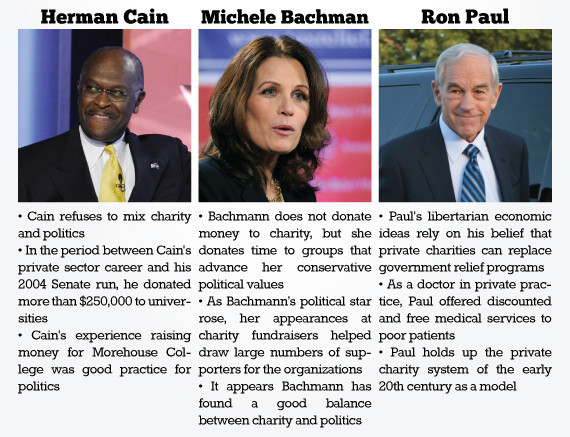

Cain does charity or politics, but not both

Cautionary tales like Santorum's make it easier to appreciate Herman Cain's decision to avoid mixing charity and politics altogether. According to Cain's friend Mike Green, the logic behind this is that Cain devotes himself wholeheartedly to every project he takes on. "One of Herman’s philosophies is he would pick one [charity] and devote all of his efforts and try to make a difference in one place," Green told HuffPost. That place has been Republican politics in recent years, but it wasn't always.

(Cain, cont.) Cain has yet to release his tax returns and doesn't have a family foundation, but his two biggest gifts appear consistent with this "all-or-nothing" strategy. During the six-year period between Cain's 1998 retirement from Godfather's Pizza and his first major campaign in 2004, the former restaurant CEO donated $150,000 to the University of Omaha and at least $100,000 to his alma mater, Morehouse College. For Morehouse, Cain went a step further, agreeing to serve as one of three co-chairs for a massive capital campaign where he helped the school raise more than $100 million.

The campaign lasted from 1997 to 2006, during which Cain likely made thousands of phone calls and appeals to wealthy alums and corporations -- good practice for a political career. Capital campaigns typically have staff assigned directly to the co-chairs, and they require tremendous amounts of time and energy. By 2004, the Morehouse campaign was winding down, just as Cain's political career was heating up.

After a brief, failed presidential run in 2000, Cain placed second in Georgia's senate primary in 2004, losing to current Sen. Johnny Isakson. Since then, Cain's political profile has grown steadily, aided by regular appearances on Fox Business Channel. During the 2010 election cycle, his Hermanator PAC raised more than $220,000.

Bachmann strikes a balance

The type of direct fundraising Cain did for Morehouse is rare among politicians, who typically spend the bulk of their time raising money for their own campaigns. But if they can't give cash or make phone calls, a personal appearance at a charity fundraiser can go a long way. This has been Michele Bachmann's preferred method of giving back ever since she was elected to Congress in 2006.

In the past year, she has appeared at fundraisers for the pro-life Susan B. Anthony List, the Florida Family Policy Council and the David Horowitz Freedom Center. The Freedom Center, a 501c(3) charitable organization, paid Bachmann's expenses for her trip to their Restoration Weekend in Palm Beach, Fla. Bachmann's politics, tightly wrapped up in her social values crusade, are difficult to disentangle from her charitable efforts. Few liberal politicians, for instance, would enjoy an event put on by any of the above organizations.

Bachmann hasn't released her income tax returns, but a HuffPost investigation failed to find any record of cash donations she has made to charity.

According to recent financial disclosure forms, she has a book deal with Penguin for a project titled "Core of Conviction," but the value of the deal is "not ascertainable," according to Bachmann. Two other candidates, Obama and Romney, have donated the proceeds from their recent books to charity, but it remains to be seen how Bachmann will spend any royalties she receives.

Ron Paul: Charity's biggest theoretical champion

Whereas Bachmann chooses to mix charity and politics on a case-by-case basis, the philosophy Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas) keeps the two perpetually intertwined.

As a libertarian, Paul aspires to a system of radically limited government, where individuals, not the state, are responsible for caring for the most needy. A key component of this, Paul says, is a "generous society," where charitable citizens and nonprofit groups perform many of the services currently provided by government, including disaster relief and health care for the poor.

A physician by trade, Paul is fond of telling voters how he offered medical care at reduced prices to those unable to pay. He also donated money to an informal fund established to help pay the costs of cancer treatment for a longtime staffer, Kent Snyder, who died last year with more than $400,000 in unpaid medical bills. Paul has yet to release his tax returns, and a spokesman declined to answer questions about his charitable record.

Like Bachmann, Ron Paul doesn't have millions of dollars to give away, so it's impossible to compare his giving record with those of candidates like Huntsman or Cain. But his statements suggest that if he did have millions, he would donate them close to home.

The retiring lawmaker speaks highly of the charitable environment of the early 20th century, a time when private charity and local governments cobbled together funds for "poorhouses" that served the function of a social safety net. Charitable giving a century ago "flourished" in America, Paul says, driven by organizations that "devoted themselves to helping those in need." He believes the current combination of taxes and government welfare programs work to prevent the average citizen from being as generous as he or she would be otherwise.

It's impossible to prove that people wouldn't give more to charity if there were less government relief, but even conservative economists believe that Paul's theory is, at best, unrealistic -- at worst, deeply flawed.

* * * * *

Charity originally meant donating money to help the poor, but this definition is rapidly changing. Today, Americans donate more money than ever to cultural institutions like museums and elite universities, which have limited, if any, direct impact upon the most needy. During the same period, large gifts to social services charities have dwindled in this country. The reasons for the shift are varied, and certain causes, such as college scholarships, don't fit easily into either category. But among the 2012 candidates, Romney, Huntsman, and Obama deserve special recognition for their commitment to the original intent of charity.