"28 Chinese" have landed at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco -- an offbeat tally, given that the number we're more used to seeing in front of the word "Chinese" is "one billion." A smattering of the work of these contemporary artists, culled from the permanent collection of Miami collectors Mera and Don Rubell, line the pristine white walls of the ground floor Osher gallery. Other paintings, sculptures, photographs and video installations appear to have parachuted, to spectacular effect, into the byzantine nooks and crannies of the museum (once home to the city's public library), alighting amid clusters of ancient jade and earthenware, elaborately carved Buddhas, samurai swords and Malaysian daggers.

The placement of these artworks is disconcerting and, for the most part, brilliant. Viewing the modern work next to ancient artifacts from China and from neighboring countries with which it has had a volatile history, instantly rewires our brains.

Ballet to the People nearly tripped over the life-like figure of celebrity artist Ai Weiwei, which lies face down on a gallery floor, as if shot to death among artifacts from the Silk Road. Crafted from fiberglass and silicone, the work by He Xiangyu borrows its title, The Death of Marat, from Jacques-Louis David's 1793 portrait of the martyred French revolutionary.

A pair of ferocious Tang Dynasty tomb guardians in glazed earthenware -- Buddhist-inspired warriors -- overlook the "corpse" of China's most notorious living artist, who has effectively been under house arrest in Beijing for the past four years, while still managing to create work for exhibitions around the world, most recently on Alcatraz Island.

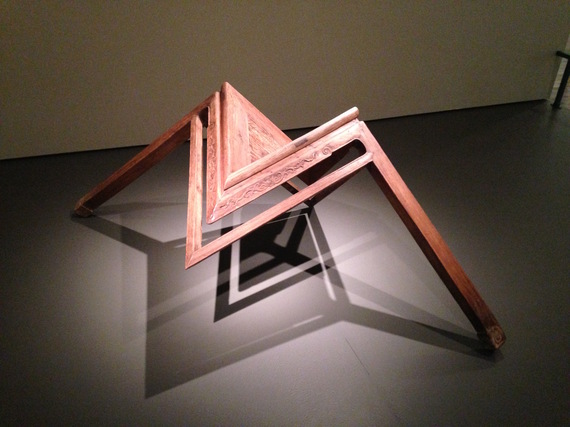

Horning in on a cluster of delicate teapots and vessels from the Qing dynasty are two of Ai's sculptural works. A Ton of Tea compresses and configures a ton of Pu'er tea leaves into a massive, dark cube that could be mistaken for rusted metal. Table With Two Legs started out as a Qing dynasty table, which Ai disassembled and reconstructed in origami-like folds, robbing it of both function and its original, highly revered aesthetic. There is a delicious Alice-in-Wonderland quality to this corner of the gallery.

More life-like sculptures -- this time of influential art theorist Joseph Beuys leaning over a bemused Mao Zedong, apparently intent on explaining an artwork to him -- are lifted from a larger installation by Li Zhanyang that satirizes the contemporary art scene in China. That installation was in turn based on a set of Social Realist sculptures, created in 1965, depicting the oppression of poor farmers by evil landlords, before the Communist Party came to their rescue.

As displayed here, Beuys and Mao are surrounded by ornately lacquered objets, their attention focused on the image of a nude woman bathing by a river, painted in the style of bad-Renoir-knockoff. (The painting is a con, engineered by artist Wang Xingwei to mock the expansive and profitable European replica painting industry in China.)

Of Mao, Li writes, in the caption to the installation, "his Cultural Revolution should be regarded as the largest piece of performance art in the world... [which] left everlasting pain for the Chinese people."

Mao's regime strangled artistic expression. In its aftermath, the development of art in China has proceeded like a series of earthquakes triggered by the harnessing of capitalism in China's quest for hegemony, by the capricious waxing and waning of censorship, by the rapid rise to international fame of a handful of émigré artists and by advances in information technology which have opened windows to the Western art world for artists who remain in China.

Of the 28 represented in this exhibition, a handful, like Li and Ai, address sensitive political themes head on in their work. But the older generation of Cynical Realists -- much of whose art reflects the barbarities of the Cultural Revolution and the massacre at Tiananmen Square, often with surrealist glosses on Party propaganda -- are not represented here. Most of the 28 were mere toddlers at the time of Tiananmen Square. The shadow of revolution has receded, and their work instead reveals a broad range of preoccupations, from the impact of rapid industrialization, to the rise of consumerism, the fakery that pervades the consumer and art markets and the challenges of new media.

In the age of the selfie, the artists themselves often feature in their own work. It is impossible to turn away from Zhang Huan's photographs of himself. 12 Square Meters documents a performance in which he coated his naked body in honey and fish sauce and sat completely still for one hour in a Beijing public toilet, in 100-degree heat, as flies swarmed and stuck to him. In the profile shot, his bearing is aristocratic, stoic.

For 1/2, Zhang's friends wrote all over his head and body in black ink, after which he draped the rib cages of bloody pig carcasses over his shoulders -- like a fashion model with haughty expression, showing off a mink coat.

Zhang is one of many barely discernible participants in his famous To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond (Distant) photograph, for which he gathered over 40 immigrant workers. He had them stand chest-deep in an enormous lake, facing the camera, with the purported intention of displacing the water -- as if they were bits of an agricultural apparatus. The photograph is displayed in a gallery peopled with ancient, intricately carved statues of bodhisattvas: enlightened Buddhist deities squaring off against subsistence laborers thrown into dangerous and pointless exercises that they barely comprehend.

In a more mischievous vein, Hu Xiangqian filmed himself sunbathing in the nude (Sun) over a period of six months, his hair in dreadlocks. His aim was to darken his skin to match that of his African friends. The absurdity is heightened by the recent brouhaha over Rachel Dolezal -- a white American who also baked for hours in the sun and styled her hair in order to pass as black. She justified her deception by claiming a strong empathy for black people and black culture.

There is a disquieting aspect to Hu's performance beyond the identity politics. China has, in the past decade, been rapidly expanding investment in Africa. Despite its shared identity with African nations as historical victims of Western colonialism, China's motives have increasingly come under suspicion, and it faces increased hostility as its hegemony on the continent grows.

Colonization of another kind is tackled in an entire room devoted to He Xiangyu's Cola Project. The exhibit documents the yearlong process of boiling down 127 tons of Coca-Cola into a toxic sludge, the final residue exhibited in a large glass box. The hazardous enterprise undertaken by the artist and his assistants, as revealed in a series of grim photographs, looks like something out of Upton Sinclair.

The serenity of the abstract paintings in the Osher Gallery provides a striking contrast to the busyness of the installations elsewhere around the museum.

The most serene of these is Xie Molin's minimalist Gradation No. 3, a series of tightly spaced, undulating white lines created with great precision by a digitally controlled device invented by the artist. This device runs a blade through the paint to cut deep grooves into it, to powerfully hypnotic effect.

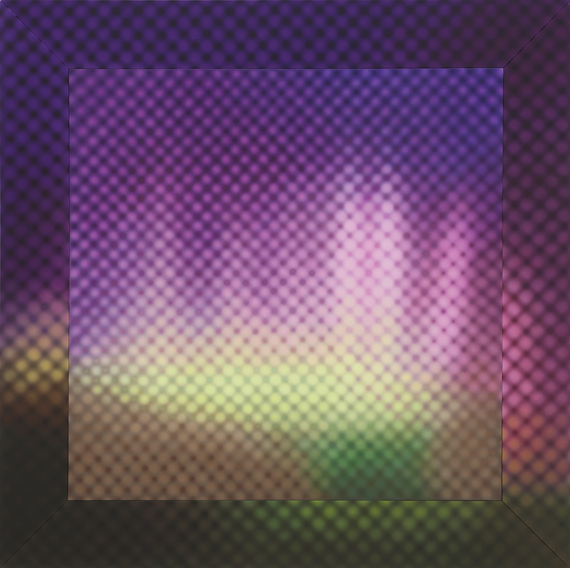

Hypnotic and shimmering are the paintings of Li Shurui, one of only two women among the 28. I am not ready... is one of a series of attempts to reproduce light. Li works in tiny square units on the canvas, like pixels, in the old days when pixels were bigger and you could see them, if you squinted hard. Behind a surface that seems to pulsate with shifting colors, lurk the mysterious outlines of a landscape that we can barely make out -- as if we are looking out a church window of modern stained glass.

The water Li uses to mix her paint and wash her brushes comes from wells dug by villagers in Blackridge (Heiqiao), where she keeps her studio. Blackridge is a concrete village outside Beijing, home to the manual laborers who build and repair Beijing and keep it functioning. Li wouldn't dream of drinking the water from the wells, which comes out of the tap thick with silt, but she will paint with it.

Liberation No. 1 by Liu Wei dominates a wall: myriad lines generated by computer software, which Liu then instructed his studio assistants to fill in with color, according to a logic which he devised. The mural resembles a psychedelic EKG readout, or the flickering patterns generated in the degaussing of a CRT TV screen. There is the undeniable hint of a generic city skyline -- an army of skyscrapers illuminated by a violent sunset.

Comrade, Your Temperature is Back to Normal, by Li Songsong, was inspired by a 1960's propaganda photo extolling the quality of China's medical care. Paint in a muted palette of pale greens and creams is thickly slathered onto the canvas, in almost slapdash fashion, so that the details become hazy. We can just make out the nurse with a mask over her face, tending to a bedridden patient. Embedded underneath the paint, the artist tells us, is an old mercury thermometer. Our eyes are drawn to a vase of pale pink and white flowers at the center of the painting, a touch of Cezanne at the heart of this morosely bureaucratic scene.

The single letdown is Zhu Jinshi's colossal Boat, a quixotic cylindrical enclosure formed by bamboo rods about 12 meters long, over which are draped 8,000 overlapping sheets of translucent rice paper, like delicate white laundry hanging out to dry. The entire contraption is suspended in the air by delicate cotton threads, providing space for humans to walk through it.

Shoehorned into the Museum's North Court, Boat fails to capture the imagination the way it did earlier in the spring, when it was on display in the vast public rotunda at Exchange Square in Hong Kong, during that city's orgy of art fairs that culminated with Art Basel. Breezes whistling through the rotunda set Boat swaying, and the chatter of business being transacted in the financial heart of the fastest-paced city in the world was suddenly muted as one stepped into the airy tunnel. Ballet to the People had the sensation of being swept along a vast ocean while hidden in this whimsical cocoon.

In the North Court of the Asian Art Museum, there is a hush all round, and not a hint of moving air; this Boat floats on a becalmed sea. It would have made a stronger statement in the Museum's spacious Samsung Hall, against the rich Beaux Art architectural detail.

Boat resonates in these times of geopolitical angst, as China has moved rapidly to assert its dominance in the South China Sea. It has seized control of vital shipping lanes and valuable fishing grounds, wrested resource-rich islands from its less powerful neighbors, reclaimed land around the islands and is building piers, airstrips, telecommunications and military facilities.

China has not been a naval power since the 19th century, when it suffered a string of humiliating defeats against Europeans and the Japanese. During the first Opium War, Chinese war junks were no match for the British steamboat Nemesis, owned by the East India Company, which, even though it had less firepower than Royal Navy warships, was ideally suited for navigating Chinese rivers.

Currently, China possesses only one aircraft carrier, a Ukrainian hand-me-down, and it will take at least a decade to build a true blue water navy. In the meantime, it fields flotillas of warships and coast guard vessels to shoo off Filipino and Vietnamese fishing boats, and to protect its massive construction operations in the Spratly Islands. Its indignant ASEAN neighbors have failed to cobble a united defense, while the United States is distracted by expensive wars in the Middle East.

China's main frontline opponents in the South China Sea are Vietnam and the Philippines. Analysts in both countries strongly fear that Beijing will seek to make an example of at least one of them, following the venerable Chinese adage that one kills a chicken to scare the monkeys. The question would seem to be which neighbor will serve as the sacrificial chicken; which country China will bully and humiliate as an object lesson to other neighbors that resistance is futile and decisive help from the Americans is unlikely to come.

- Howard W. French, "China's Dangerous Game," The Atlantic (November 2014)

Amid fraught speculation over whom China will attack first, many forget that China already has a longstanding onshore presence in these countries.

Spitting distance from "28 Chinese" at the Asian Art Museum, Hector Berlioz' "The Trojans" exploded on stage at the War Memorial Opera House, in a magnificent and chilling production by the San Francisco Opera. The sight of that massive scrap-metal horse advancing on the orchestra pit, flames shooting out of its mane, reminded us that China has fielded its own Trojan horses. It already controls sizeable chunks of the economy of every ASEAN nation - and with its just-launched Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, earmarked to fund vital infrastructure, it will likely cement its grip on the region.

Bewitching soprano Anna Caterina Antonacci gave a blistering account of the prophetess Cassandra, who warned the imprudent Trojans to fear the Greeks, even when bearing gifts.

A handful of audacious Chinese artists -- like Ai Weiwei, a perpetual thorn in the side of the Chinese government -- may well turn out to be the Cassandras of their generation -- even as their work sells at international auctions for millions of dollars a pop.

The entire contemporary art movement can be seen as part of China's bid to become a global power, to recover the dignity lost during a century of humiliation at the hands of Western and Japanese colonial powers.

A blue water navy may ultimately prove less strategic to China than Zhu Jinshi's fanciful Boat.

28 Chinese runs through August 16, 2015, at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin St. in San Francisco.