April 17th, 2015 marks 40 years since the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh and unleashed a wrath of vengeance against its own people. The genocide war in Cambodia left almost 2 million people dead from execution, starvation and disease. The educated class, government officials, and the wealthy were targeted in an effort to purge the country of anyone or anything associated with colonial influence or class structure.

The Khmer Rouge attempts of creating a self-sufficient society based on radical communist principles left the country ravaged and barren. After the war, each and every survivor has stories to share -- how they survived, the tortuous ordeals they faced every day, what, and more importantly who, they lost. There is one thing that my parents, especially my father, still talks about 40 years later. He always speaks of a dream he had during the first week of evacuation from the capital city of Phnom Penh. Literally, it was a dream that he had and how that dream led him to find his new place that allowed him and my mother to survive, and of course for me to write this story.

The stories I have heard since I was a young child continue haunt me, and the bits and pieces of the puzzle never quite formed a solid picture of what really happened. Forty years later, the story of my family's experience was still a mystery to me. While other stories from survivors were clear in my mind, I never heard the entire story from my parents, until now. Perhaps it was my frequent visits home, with cohorts of inquisitive graduate students that prompted me to ask, in detail, the story I had wanted to hear. It was never a question that surfaced in my mind as one that should be asked. As a child of genocide survivors, it was something I feared, something I ignored. Yet, the more students I brought to Cambodia, the more their questions made me realize that the genocide was something that needed to be told. My family's story was not something to be ignored, but rather something to be acknowledged, both for the survivors themselves and for their children. And so begins the story of one family, who much like the rest of the Khmer people, faced tragedy and immeasurable sorrow, and somehow found a way to survive.

At 4:00p.m. on April 17th, my family was informed that the Khmer Rouge (KR) soldiers were evacuating Phnom Penh for three days due to an impending U.S. military strike. My parents knew of what the KR was planning, what they had already done outside of the city. My father worked at the Social Republican Party Headquarters, the officially recognized government, backed by the United States, led by Marshal Lon Nol. He was responsible for inspecting security and social order in various provinces across Cambodia. As a liaison between federal and provincial officials, he often traveled to meet with governors to assess the safety and security of the province and reported his findings to the Ministry of the Interior. My family could have escaped during Operation Eagle Pull, the United States evacuation of Phnom Penh, but my father felt that by leaving, he was saving himself and my mother and abandoning everyone else he loved. He would rather die trying to save them than try to live with the guilt of leaving them behind.

So there they were. Operation Eagle Pull was successfully completed days before, and the time had come to face their new reality. There was no getting out, nowhere to run, and no one coming to save them. The night of April 17th they packed everything they could, including mats, cooking pots, and other significant belongings such as their wedding photo album (married 2 years earlier) and some jewelry they could hide in their belongings. The next morning, they heard the KR make an announcement that all people in Phnom Penh should return to their homeland, the villages of their families, extended families or ancestors. My father knew that if he went back to his province, Kampot, he would die. Instead, he decided to go to a new place, in the direction of Vietnam, along with my mother's sisters and both of her parents. My father knew that if they could reach Vietnam, they would all have a chance for survival. The mass exodus of the city was so congested that it took them three days to travel six miles, reaching this district called Prek Eng. "It felt like it took one meter (or 3 feet) for an hour walk," he noted. At Prek Eng, he felt something was trying to stop him from going forward. So he stopped there, and stayed for the night.

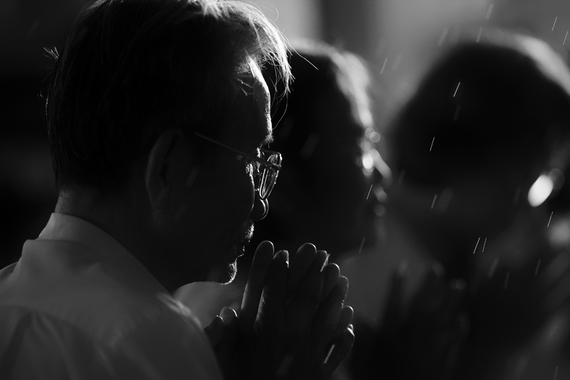

That night, my father lit 34 incense sticks and prayed for a sign for the best place to relocate in his dream. My father dreamed that night, not of a map of a place he had seen before. Instead, he dreamed of seeing lots of broken bamboos, and every one of them was broken. Early dawn, he discussed the dream with my grandfather. He immediately referred broken bamboos to this village called "Puk-Russei," literally meaning broken bamboos. Puk-Russei was the name of a village where my aunt's in-laws lived. So they decided to cross the Mekong River from Prek Eng to come to the Broken Bamboos village.

Upon arrival at Puk-Russei, KR officials were there to thoroughly document their background. They asked where my family came from, what they did for a living, and if my father was a former soldier. They knew that acknowledging their past would lead to their swift and brutal executions. My father's response was a lie -- he said he was illiterate, selling baguettes, by foot, at the Phnom Penh Port. The KR officials allowed them to stay but kept coming back, documenting my family background almost everyday for a month, searching for inconsistencies and reasons to distrust my family.

One night, three KR soldiers came to the house around 9pm. They took my father away, and it was clear by this point in the revolution that leaving home in such a way meant never coming back. It meant imminent death. Again, after nearly a month, he was asked the same background questions. He never wavered in his answers, never revealed his true identity. After three hours of questioning, he was released. He got home at 2a.m. after an hour walk from that interrogation place, Toul Sdey. "Your mother had no idea where I was," he said, while looking at her. The secrets they kept as a family would be the difference between life and death, and everyone knew it.

In total, my father was "taken out" to get killed three times. One afternoon, as he was watering vegetables in the community garden, he was approached by KR soldiers instructing him to leave the garden and follow them. He survived by telling them that the vegetables needed to be watered now, otherwise the plants would die and the whole community would starve.

Several months after the evacuation, my mother delivered a baby girl. About three months later she had a postnatal complication and was sent to a KR hospital at Viheasour commune, about 12 Km (about 7.5 miles) east of their house. She was at the hospital for a month, leaving my father to feed the three-month old baby with just rice porridge.

While my mother was hospitalized, the KR soldiers came to the house yet again, this time instructing my father, the baby, my aunts, and grandparents to follow them. They were taken to a large boat, able to accommodate several hundred people. Inside the boat while people were still boarding, the baby girl started to cry, strangely loud. My father asked the KR officials if he could delay his departure just until my mother got discharged from the hospital so that the baby could have breastmilk. The KR officials looked up his name, pulled out a pen, a red-inked pen, and crossed out his name. They took my father and the baby home on a cart with KR officials, pulling them all the way home. My father thought at that moment perhaps the spirit of the temple where the boat docked helped him, and perhaps they did.

The boat left with all of my mother's sisters and parents. They have yet to return home.

While my mother was still at the hospital, the baby was getting sick. "The baby had diarrhea," my father said. A few days after my mother arrived home, the baby died. "The baby was waiting for her mother to come home before she left, forever" added my father. A few days before the baby died, someone came by the house and told my father that my mother was ready to return home. He borrowed a bicycle from the Angkar (KR referred to as The Organization), left the sick baby at home alone, and went to pick her up. When I asked my father what baby looked like, he jokingly said "she was exceptionally beautiful, with white smooth skin, and even much more beautiful than your sister" who sat next to him and my mother during our talk.

The baby was not the only sibling of mine who died during the war. Three others, two boys and a girl, within those three years, eight months, and twenty days, joined my family only to be stolen by diseases all too common during the KR regime. Around the first week of April there is a traditional event called "Qingming," a "Tomb-Sweeping Day" or "Ancestors' Day," and I asked if my parents remembered where my sister and other siblings were buried, so that we can transfer the merits to them, but they could not locate the place.

Immediately after the war ended in January 1979, my father was free to unwrap the cloak of lies that protected him and my mother for almost four years. He became a principal of a junior high school in the village. Everyone said to my father, "You are a nail-hidden cat." My father has since helped many older children in the village and those nearby, to get education. These children were old enough to be listed to join the K-5 Plan, a plan that began in 1984 until 1989, to seal the Cambodia-Thai border to prevent the return of KR by clearing forest, wiring fences, laying mines and other means. He took these children to stay in school. Growing up, I remember many of his students came to visit him with bags of nice rice and other produce to thank him.

My parents currently have three children, two sons and a daughter--all of us were born after the war ended. This year, my mother reaches 72 and father 74 years of age. They said Puk-Russei village gave them a life. They will forever call it home. I grew up there till I finished my high school before moving to Phnom Penh for my college, and later to Lubbock's Texas Tech University for my graduate school.

From time to time when we meet, my parents, especially my father talks about that dream and how fortunate they were to survive. Most of their family and friends were not as fortunate. While my parents suffered the pain and sorrow of losing their children, they have shown my brother, sister, and I, the importance of faith and family, and hope.

My mother offering food to monks every single day, wishing for the betterment of her rebirth. Photo: Sothea Eng

Until now, both of them still believe in dreams. Last year, we, three of us children, offered them their wish by having a "merit-transfer ceremony to the next lives and to the dead relatives" based on the dream that my father had that year.

Sothy Eng, Ph.D., is a Professor of Practice of Comparative and International Education at College of Education's Lehigh University in Bethlehem, PA.