This Post originally appeared on the blog ScreenCraft. ScreenCraft is dedicated to helping screenwriters and filmmakers succeed through educational events, screenwriting competitions and the annual ScreenCraft Screenwriting Fellowship program, connecting screenwriters with agents, managers and Hollywood producers. Follow ScreenCraft on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

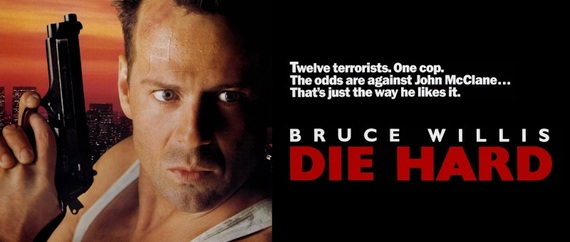

Die Hard, written by Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, has stood the test of time as not only one of the best action films in cinematic history, but also as one of the best scripts ever written. ScreenCraft featured it in 10 Scripts to Read Before You Die.

The film debuted in 1988, released during a decade in which the action genre was at its highest, having given birth to action icons like Arnold Schwarzenegger (Commando) and Sylvester Stallone (Rambo). Those two figures dominated the action genre with the likes of other action stars later in the decade -- Dolph Lundgren, Jean Claude Van Damme, Steven Seagal, and Chuck Norris before them.

During this decade, the action genre at that time was pretty simplistic, with the exception of Lethal Weapon, released the year before Die Hard. You had your nearly invincible hero, with a seemingly endless amount of ammunition and skills, facing a fairly typical villain that had somehow wronged the hero -- launching them on a mission of revenge, to rescue someone close to them, or to just solve that case that no one thought possible. The stories varied, but the end results were the same. Bullets and fists would fly and the bad guys would pay with the hero coming out virtually unscathed.

Die Hard changed all of that.

It’s strange at first because if you look at the bare bones of the concept, story, and character, Die Hard doesn't sound that much different than something Arnold and Stallone would have starred in. Ironically enough, both were considered for the role of John McClane (as were others like Nick Nolte, Don Johnson, and Richard Gere). We have a cop, terrorists, and many bullets. Sounds like an '80s action flick to the core. Perhaps if Arnold or Stallone would have signed on, it might have been a run-of-the-mill ’80s action feast.

However, Die Hard was different.

Let’s explore five lessons that Die Hard can teach us about writing action and thriller stories -- or any story in any genre. While they may seem minuscule as laid out below, collectively they offer writers ways in which they can add more depth to the characters and stories.

1. Make Your Heroes Vulnerable

Like Lethal Weapon before it (both of which were produced by Joel Silver), the hero of Die Hard wasn't as invincible as their '80s action genre counterparts. Go watch Commando and Rambo: First Blood Part 2 and witness how those heroes were virtually invulnerable. Sure, we'll give Stallone's original First Blood early kudos for allowing some depth and vulnerability to an otherwise outright action hero -- he did suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and even cried (we'll get to that later) -- however, Die Hard took it up a notch.

John McClane wasn't just a cop in the wrong place at the wrong time. Okay, that's kind of John McClane's thing, yes, but as a character, he was more than that. He was a father. Beyond that, he was an estranged father. He was also a husband. Beyond that, he was an estranged husband. He wasn't cool about it. He wasn't indifferent about it. He was conflicted. He wanted his wife back but he also struggled with her decisions regarding their marriage. And to top it off, he didn't like himself very much. He comes off as overly confident, however, he's all too often talking down to himself under his breath.

He's vulnerable. And what that does is allow audiences to relate to him.

We don't relate to invincible soldiers of war with endless ammunition and skills that can fire endlessly hitting every target -- killing dozens with ease -- while barely a single bullet grazes their skin. We relate to the family man that is far from perfect.

Making your heroes vulnerable opens doors to a wider audience, which leads to the ability to market the film to more demographics, which leads to better odds of getting your story purchased, produced, or published.

2. Pepper Your Stories with Conflict

Conflict is everything. While the story had plenty of conflict to behold -- terrorists, hostages, guns, etc. -- the reason Die Hard stands out so much in regards to conflict is that it is peppered with it. Those smaller details of conflict are what makes this film stand higher than the rest.

Case in point, look no further than McClane's bare feet. If you remember, when the terrorists first attacked, he was barefoot making fists with his toes to combat jet lag.

This leads to a moment of minor conflict after McClane kills a terrorist and hopes to utilize the dead man's shoes, only to discover that the terrorist has "feet smaller than [his] sister." This then leads to a major conflict after Hans Gruber, the main villain, knowing that McClane is barefoot, orders his men to shoot the glass during a shootout. McClane is forced to run through the glass to escape, shredding his foot into a bloody pulp, and then leading to a further moment of vulnerability (see above) as he shares an emotional moment with his police officer companion on the outside, Al Powell.

It's easy to see that the situation within the story seemingly already had enough conflict, but even more depth was added to it with this very little, but significant detail.

As we showcased above with the vulnerability found in the main character, we're given even more conflict. Not only does the hero have to defeat the terrorists, he also has to save his wife and in turn, his marriage, as their love is rediscovered amidst the chaos of the situation.

Then, the hero has to deal with not only terrorists and the thought of having to save his wife, he's also confronted with a police authority figure that doesn't believe his story and wants him to stay out of their way.

As if that wasn't enough, two FBI agents that are overly gung-ho threaten not only our hero, but the hostages as well, having accepted the idea of collateral damage.

And then we're still given even more conflict with an asshole news reporter looking to break the story, which leads to even more conflict when the reporter outs John McClane on air while the terrorists are watching, and furthermore connects McClane to Holly "Gennero", otherwise known as Holly McClane. Hans makes the final connection when he sees a picture of John, Holly, and their children.

On the flip side, not only do the terrorists want to eliminate the sole cowboy making a mess of their plans, one of them wants blood in a vendetta that began with McClane killing a terrorist that happened to be his brother. Now Hans must keep this terrorist, Karl, on a short leash as he tries to deal with everything else.

And finally, down below in the parking garage, sits Argyle, McClane's limo driver, stuck behind closed gates in a building full of terrorists.

Other seemingly small sources of conflict pay off in spades, heightening the overall tension and believability of the premise, and furthering the portrayal of McClane as a regular joe and an audience surrogate: McClane tied to the hose that, after saving him from a long fall off of the building, now begins to drag him to his death; once McClane finally has a chance to save his wife with the element of surprise, he only has two bullets left with two remaining armed bad guys… so he can't afford to miss.

Conflict is everything. Big or small. If you pepper your story with conflict that lies beyond the central premise, you give the story continued depth, engaging the audience with each and every turn of the page.

3. Location is Key

The Nakatomi Plaza is a character in itself. If the terrorists were the personification of evil within the story, Nakatomi Plaza was the otherwise neutral force of nature within the situation, confining the hero and forcing him to survive amongst its "elements" of steel, dry wall, and glass, not to mention the building's most terrifying hurdle for McClane, its height.

No different than the thrillers The Towering Inferno and The Poseidon Adventure before it, Die Hard offered one of the greatest examples of importance of location.

Location is a character. It offers added conflict, another hurdle that the hero must overcome. There's a reason that this film gave birth to a sub-genre ("Die Hard on a...") that flourished with the likes of Under Siege (aircraft carrier), Passenger 57/Executive Decision/Air Force One (airplane), Speed (bus), Sudden Death (hockey rink), Cliffhanger (mountains), The Rock (Alcatraz), Olympus Has Fallen/White House Down (the White House), etc.

If you can find an interesting location to set your vulnerable characters in, it only adds to the conflict that you can create.

4. Supporting Characters with a Little Story of Their Own

Notice that I say little. You can't give each supporting character major screen time, however, you can offer small moments that add to the big picture (pun intended). Let's examine the supporting characters of Die Hard beyond John McClane, his wife, and Hans Gruber.

Al, McClane's partner via radio, shot a kid. He’s haunted by it. He doesn't want to draw his weapon on another person again.

Argyle, the limo driver, is stuck in the garage watching and listening to the chaos around him.

Ellis, Holly's sleazy coworker, is an egotistical asshole that thinks he can negotiate his way out of anything.

Karl, the terrorist, has lost his brother at the hands of McClane.

And each of these little stories have their own beginning, middle, and end. They each have their own payoff. Al saves the day with the firing of his weapon. Argyle saves the day, crashing into the terrorists’ van and punching out one of the remaining bad guys. Ellis succumbs to his moronic ego. Karl faces off against the man that killed his brother.

Even on a smaller level, we're given characters that stand out with their own personalities. We have Deputy Police Chief Dwayne T. Robinson, an asshole authority figure that gets in McClane's way. We have Agent Johnson and Agent Johnson (no relation), two FBI agents that are overly gung-ho about their approach to the terrorists. We have Theo, the comic relief bad guy that cracks jokes.

All of them stand out amongst the many other supporting characters in similar action thrillers, if not because of the little stories of their own, then due to the little character traits that make them stand apart from the clichéd cookie-cutter bad guys, whom I call bullet catchers.

5. Crafty Foreshadowing and Payoff

Remember the smaller elements of conflict that are peppered throughout the Die Hard story? Each of them are properly and brilliantly set up early on.

In the opening scene of the film, the fellow passenger sitting next to McClane on the plane tells him that the secret way to get rid of jet lag is to make fists with his toes while barefoot and walking on the carpet.

This of course leads to an ongoing series of pivotal moments throughout the whole story.

Nakatomi Plaza, our example of location is key, solidified that point over and over, as it foreshadowed eventual events in various locations of the plaza throughout the story. The elevators, the parking garage, the lobby desk, the executive bathroom, Holly's office (with the picture that she overturned early on), the staircase where Karl and McClane fight, etc. These are all brilliantly set up early with eventual payoff.

Lastly, one foreshadowing moment that is all too often left forgotten, the watch that Ellis so arrogantly points out to McClane that he gave to Holly, plays a pivotal role in the narrative, leading to one of the greatest villain deaths in cinematic history.

Needless to say, given the examples offered above, Die Hard is one of the greatest scripts ever written, proving that writers can make their action thrillers (or any genre) even better by making their heroes vulnerable, peppering their stories with conflict, setting their stories in key locations that become characters themselves, offering supporting characters with a little story of their own, and providing crafty foreshadowing that leads to some great payoffs.

Take it from a former studio script reader, these are elements that will make an otherwise routine action, thriller, horror, suspense, comedy, or drama story shine. And if you can win over that script reader or editor, your odds of success increase dramatically as they pass that script or manuscript up to the powers that be.

So take this list of five lessons to learn and go look over your own stories. See if you can find ways to make them shine even brighter.

If you have an action or thriller script of your own, submit it to ScreenCraft’s Action & Thriller Script Contest!

More from ScreenCraft: