The kid started smoking at 5 and drinking at 8. He ran away over and over, fought in the streets, and robbed strangers and neighbors alike. He slashed his teachers' tires, threw things at cops, and vandalized train tracks. Sounds like a parents' worst nightmare, doesn't he?

A little later, he shook hands with Adolph Hitler.

Pretty soon after that, things went downhill.

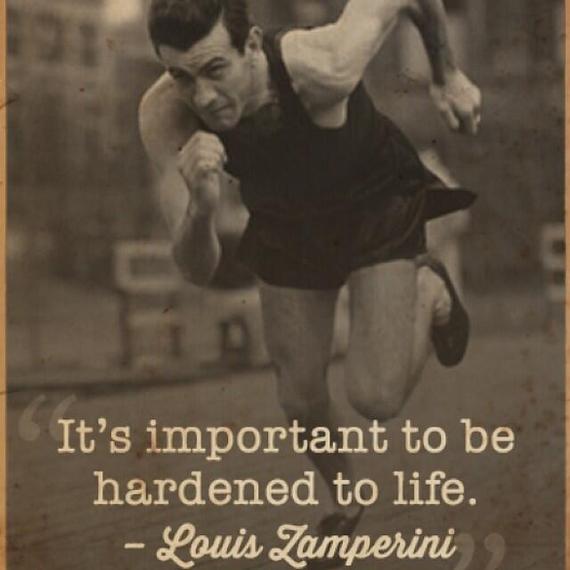

Yet Louis Zamperini, the real life hero in the movie Unbroken and the book of the same name by Laura Hillenbrand, became an adult who personified character. Battered, bruised, fraught with repeated catastrophic chaos, failure and defeat, Lou embodied resilience, and its essential ingredient, character. Much of his character is formed in childhood experiences that may surprise you. (Some experiences described here are drawn from biographical sources other than the movie and book.)

No one in their right mind would suggest replicating the perils Louis engaged in, but there is much to learn from what was done with what he did.

Here are eight things parents can learn about character building from Unbroken. :

1. Failure's benefits are activated in a secure relationship.

Speaking no English, Louis was an easy target for brutal bullying in his California elementary school. His father knew less English than Louis, so he helped by spending many hours teaching his son to box and encouraging his physicality. A landmark study that examined the effects of adverse childhood experiences ("ACEs") described by Paul Tough in his book How Kids Succeed, illustrates the importance of the "one person" in an intense relationship that helps a child deal with failure, not prevent it from happening. "What you are learning is how to deal with failure and how to learn from failure," Tough told The Washington Post. While teaching your kid to box may have mixed results, the hours Lou and his father spent together in pursuit of a difficult physical goal enabled an intense relationship that hot-housed repeated failures and ultimately success. Learning to cope with failure is easier as a joint effort. Failure experienced alone often fuels shame.

2. Empathy can grow in strange ways.

A successful liar is good at empathy. Caught by guards for stealing a Nazi flag, Lou intuited the answer that would be the most persuasive: "I wanted to take the flag home to remind me of the wonderful time I had in your country." While lying is not a skill most parents would encourage, there is evidence that the skill set that enables a successful liar overlaps with those skills that empower leaders. Researcher Caroline Keating studied children and adults and found that the ability to lie successfully was the best predictor of dominance, or leadership, particularly among men. Anyway, lying is a developmental milestone. A Canadian scientist who studied 1,200 children age two to 17 told the BBC: "Almost all children lie... Those who have better cognitive development lie because they can cover up their tracks. This was because they had developed the ability to carry out a complex juggling act which involves keeping the truth at the back of their brains." Lying is a complex task that requires a sophisticated understanding of others' minds, including developing empathy, and executive functioning skills.

If your preschooler lies, consider this is not a crisis of morality; he is experimenting with ways of getting what he wants. Helping your child develop morality and responsibility for his actions over the long haul is the ultimate goal, and part of that learning process is getting busted and discovering "it feels bad to get caught and for people not to trust me."

3. Risk has its own rewards.

Lou sought dangerous risks, for example throwing rocks at cops. You shouldn't let your kid throw rocks at cops. But children build confidence by doing things that feel risky, even if they aren't particularly dangerous. In 2011, Ellen Sandseter, a professor of early-childhood education, studied free play and concluded that children have a sensory need to taste danger and excitement; this doesn't mean that what they do has to actually be dangerous, only that they feel they are taking a great risk. That scares them, but then they overcome the fear. Sandseter asserts that risky play serves an "anti-phobic" function. From her perspective, evolution favored children who developed fears of certain stimuli (e.g. heights and strangers) that protect them. Risky play provides children with an exhilarating positive emotion and exposes them to things and situations they previously feared. She believes our society is at greater risk if children do not have formative risky play experiences. Fear in small doses seems to inoculate us, helps us meet bigger fears. Children are better served by parents who are able to restrain their own fear to allow risky play.

4. It takes a village.

Lou's brother, tired of getting him out of police custody, got hold of the principal of the school and the chief of police. Together they decided that sports would probably be the ticket, and then enlisted the high school track and field coach, who eventually led Zamperini to the 1936 Olympics, where the handshake with Hitler took place. He told an Olympic historian about running down the homestretch: "I heard the kids from my high school hollering, 'Come on, Louie!' I had no idea that anyone even knew my name, and yet the whole group of kids in the grandstand was hollering, 'Come on, Louie!' So I came in and got third place."

A large 2013 Gates Foundation study found that kids that participate in "mentored relationships" (an involved adult OUTSIDE the immediate family) consistently display better school attendance, lower levels of substance abuse, and surprisingly, higher levels of trust and communication with their parents. Today's parent can feel particular pressure to shape every aspect of their child's personality. But mentors from within the family system are less effective for a number of reasons according to a 2002 study. Mentoring relationships formed with individuals outside the family circle have a significant influence decreasing problem behaviors and improving psychological well-being, academic performance, and relationships with others. A parent's efforts might be better put to matchmaking: seeking out settings that might naturally grow a mentor connection for their kid.

5. Belief in things not seen.

Adding to all the stressors and uncertainties already blighting the lives of parents, religion has more recently become fundamentally challenged by a number of voices, particularly the New Atheists. At the end of the 20th century, Richard Dawkins stated: "Religion is capable of driving people to such dangerous folly that faith seems to me to qualify as a kind of mental illness." Almost two centuries ago, Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard may have more accurately anticipated current research: "The function of prayer is not to influence God, but rather to change the nature of the one who prays."

There is a good deal of empirical evidence to support the idea that concern for their child's mental health may in fact be a good reason to practice faith, however. Religious observance in families is positively associated with child mental health -- playing a beneficial role by attenuating problems of anxiety and aggression. Religion or spirituality within families has also been identified as a protective factor, as it gives people meaning in life when faced with adversity. Zamperini's story reflects some findings in much of the literature.

This generation of hope and a belief is an important theme in Zamperini's life according to the book -- particularly the themes of forgiveness, meaning and recovery after horrific trauma. The research identifies religion practices broadly and found that resilience is enhanced by the practice of a faith tradition, not the specific content of the faith.

Portraying religion generically may in be fact beneficial to audiences, perhaps the controversy about the "dismissal of Christianity," may shift more constructively to the fundamental role religion played in Zamperini's life. Perhaps such a shift could help parents sort through the plethora of arguments that seem to see what is valuable in the in practice and what elements may be harmful to a young person's development and character.

6. Spare the Rod... Please!

All parents get frustrated with misbehavior, but Zamperini's parents reached new heights of exasperation. He is seen getting severe spanking by his dad, with no effective results. Punishment, whether corporal or otherwise, is an attempt to influence the future -- reducing or eliminating unwanted behaviors. It works pretty well with the majority of kids, but there are kids that it virtually never works, if "works," means changing their future behavior choices. Unfortunately the kids that often wind up getting punished most are the ones for whom punishment works least. For kids with ADHD or who never met an impulse they didn't like, punishment is ineffective at changing future behavior, although it can immediately stop a current action ("that's it, no more YouTube for the rest of the day"). So an important question is -- does your kid's future behavior change after punishment? If not, it is unlikely to improve with increased intensity (that's it, no more YouTube for the next six months!"). Corporal punishment has so many shortcomings and complications, I argue for "Corporal Abstinence" in another article on this site.

7. Imagination can get you through hell.

Fellow prisoner of war Major Greg "Pappy" Boyington, in his book, Baa Baa Black Sheep, expresses gratitude for the Italian recipes Zamperini would recite to keep the prisoners' minds off the food and conditions. Deliberately chosen mental stimulation, in other words, "using our imagination" assists individuals both cope and achieve goals and endure or resolve difficult circumstances. Imagination and pretend play in kids is linked to both an enduring positive mood in life and overall coping ability.

8. Revenge may be sweet, but forgiveness may save your life, model it for your kids.

At Sugamo Prison in Tokyo, where prisoners that committed the worst atrocities are held, Zamperini visited many of the imprisoned former guards from his POW days to let them know that he has forgiven them. Many who recognized him came forward to have Zamperini throw his arms around each of them. The prisoners were shocked by his genuine affection for those who had once ill-treated him, but Zamperini saw forgiveness as most critical to his own survival and healing. Numerous studies indicate that forgiveness is strongly tied to psychological healing after trauma, while restoring physical health and restoring a victim's sense of personal power.

***

Parents are on more sure footing when they focus on working hard in school, learning from the vast array of cultural opportunities and developing athletic or artistic skills. The progress is more or less linear. It's easier for us to tell if we are doing a good job or not. "Our child succeeds. She is happy. We are good parents. We are happy." It's kind of like looking at the pencil markings on a wall of a child's growth.

Growing character is more complicated. Its direction is more circular, and seems to expand and contract. There is less obvious "growth," in part because the process requires a fair amount of setbacks, disappointments, tough jams, and failures.

One never knows which "failure" will be the tipping point for growth instead of merely groans. We can't tell if a certain risk might yield a discovered, previously unknown source of inner motivation. Who knows if getting "in trouble" might lead to the mentor that sees a spark in us we miss. We get caught lying or cheating at something and as a result we are denied admittance to what seems like the ticket to our early dream, only to discover our calling, more subtle but more configured to our values and strengths. What begins in error may quickly deliver us some pain, but also, over the long haul, introduce us to the longer road, the one that teaches us our character, that reveals to us the deeper realms of success.

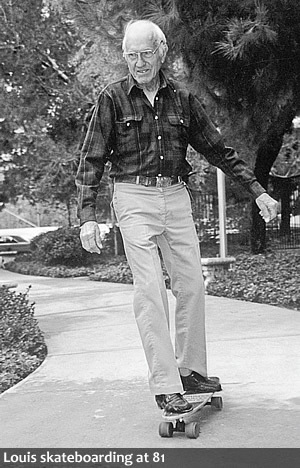

At first glance, Zamperini's life seems about survival, not growth. But a closer look reveals his life to be the embodiment of the adage "that which does not kill me, makes me stronger." The first trick -- don't let it kill you. The second is recognizing that getting stronger means discovering one is weak, and needs to wobble, struggle, and fail in order to develop the unbroken character skills to succeed. But parents, be careful. Witnessing the risks and failures that prepare your kids to be unbreakable adults might kill you.