This post was co-authored with Dr. Nazgol Ghandnoosh, a research analyst at The Sentencing Project.

By many measures, there is growing momentum for criminal justice reform. Changes in federal drug-sentencing policy, passed by Congress in 2010, will help to reduce sentence lengths and racial disparity. We hear less "tough on crime" rhetoric and budget-conscious conservatives are embracing sentencing reforms. The Attorney General has criticized aspects of the criminal justice system and directed federal prosecutors to seek reduced sanctions against lower-level offenders.

In light of this, one would think we should celebrate the new figures from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) showing a decline in the U.S. prison population for the third consecutive year. This follows rising prisoner counts for every year between 1973 and 2010. BJS reports that 28 states reduced their prison populations in 2012, contributing to a national reduction of 29,000. Beset by budget constraints and a growing concern for effective approaches to public safety, state policymakers have begun downsizing unsustainable institutional populations.

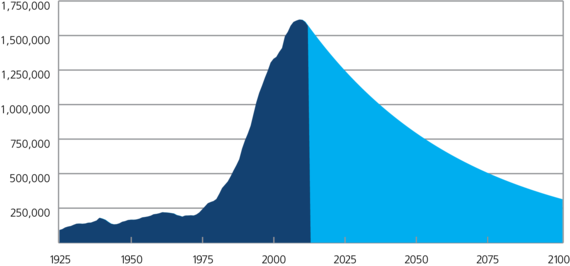

The break in the prison population's unremitting growth offers an overdue reprieve and a cause for hope for sustained reversal of the nearly four-decade growth pattern. But any optimism needs to be tempered by the very modest rate of decline, 1.8 percent in the past year. At this rate, it will take until 2101 -- 88 years -- for the prison population to return to its 1980 level.

Historical and projected U.S. federal and state prison populations,

based on 2012 rate of decline

Other developments should also curb our enthusiasm. The population in federal prisons has yet to decline. And even among the states, the trend is not uniformly or unreservedly positive. Most states that trimmed their prison populations in 2012 did so by small amounts -- eight registered declines of less than 1 percent. Further, over half of the 2012 prison count reduction comes from the 10 percent decline in California's prison population, required by a Supreme Court mandate. But even that state's achievement is partly illusory, as it has been accompanied by increasing county jail admissions.

Three states stand out for making significant cuts in their prison populations in the past decade: New York (19 percent), California (17 percent), and New Jersey (17 percent). The reductions in New York and New Jersey have been in part a function of reduced crime levels, but also changes in policy and practice designed to reduce the number of lower-level drug offenders and parole violators in prison. But the pace of reductions in most other states has been quite modest. Moreover, 22 states still subscribed to an outdated model of prisoner expansion in 2012.

Given recent policy changes, why has there been such a small reduction in the number of people held in prisons? First, many sentencing reforms have understandably focused on low-level offenders. While a necessary first step, many of these individuals would have otherwise served relatively short prison terms, making the prison bed savings of these reforms relatively modest. Second, some reforms like the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the federal crack-cocaine sentencing disparity, await judicial or legislative action to apply retroactively to prisoners sentenced under old laws. Third, incarceration compounds the problems many people had before entering prisons, further isolating individuals from family and community. The reentry movement of the past decade has attempted to address this issue, but resources devoted to such efforts are still relatively modest.

But most significantly, policymakers have neglected the bulk of those who are in state prisons: an aging population convicted of violent crimes or repeat offenses. At the extreme end, states have increased their reliance on sentences of life imprisonment, with one in nine people in prison currently serving such terms. While many of these individuals posed a public safety threat at the time of their conviction, in many cases they have now "aged out of crime" and are no longer at a high risk category.

Certainly the changing climate, new policies, and recent prisoner counts offer reason for encouragement. But unless we want to wait 88 years to achieve a sensible prison population, we need to accelerate the scale of reform. Producing meaningful reductions in incarceration will require two broad shifts. First, sentencing reforms that reconsider who we send to prison and how long we keep them there. And second, a reconsideration of our approach to public safety, with a shift toward initiatives that rely on strengthening the capacity of families and communities to produce healthy citizens, rather than relying the punitive tools of the criminal justice system.