The first week of school is always hard. There's the adjustment back into academic routine, the planning out of one's goals and schedule, and then there are the reminders that time continues forward -- unfeeling and unstoppable. The start of each new school year has been an especially difficult experience for me the last 10 years, because Sept. 11 always falls in the first week.

When I started at Brown University, I sat with a group of fellow freshmen on the seventh anniversary of September 11th. My family had just left after visiting for the day, and I was hoping no one would recognize my personal connection to the date.

There in the dining hall, the conversation came up -- my generation's version of "where were you when JFK was shot?" While the JFK conversation is polite chit-chat in front of anyone whose last name isn't Kennedy, Oswald or Ruby, there are no faces to the attacks of 9/11.

I hoped no one would ask why my grandparents had sent me a Popcorn Factory gift basket. I hoped no one would remember I was from New York. I hoped no one would ask why my father had not visited along with the rest of my family. I hoped no one would pay attention to me at all, and no one did. I sat there as the other students talked about their own memories of the day: how they left school early, how they hugged their parents and cried, and how much the experience of 9/11 had changed them.

I could have told them the truth. I could have stolen the spotlight, played for their sympathy, and maybe registered as a novelty worth knowing. I said nothing. The victim card is a powerful trump, and the silence after it's played is as powerful as it is intensely awkward.

What I remember most vividly of that morning, Sept. 11, 2001, was my middle school principal gathering all of us together, a group of sixty 10- and 11-year-olds, and looking at us with the bleak, defeated candor I have come to associate with a total loss of words: "There's been an incident."

We were on an overnight field trip. It was my first week at a new school. No one told us anything, in part, I suppose, not to scare us, and in part because they didn't know themselves what to expect. We were told to pack our things and get ready to leave a day early. This was a time to be with our families.

We arrived in the school parking lot after dark. The bus was surrounded by parents, holding hands against their nervousness, presenting a tough front to support their children. I picked up my bag and scanned the crowd. My mother was alone. She was crying.

My memories get a little fuzzier after that.

My grandfather drove us home. I remember lying with my head in my mother's lap, and my vision blurring as we both wept. I remember arriving in my bedroom, and finding a stack of new comics I had ordered. The cover of Batman #428 stared back at me, the climax of the "Death in the Family" story arc. Robin lay bloody and broken -- dead after being caught in a building explosion.

I knelt by my bed and earnestly prayed. On some level I hoped. I remember protesting that it was too soon to give up when my mother scheduled the memorial service a few weeks later, citing that people had been found in the wreckage of ground zero, but in the words of that prayer I admitted something I already knew.

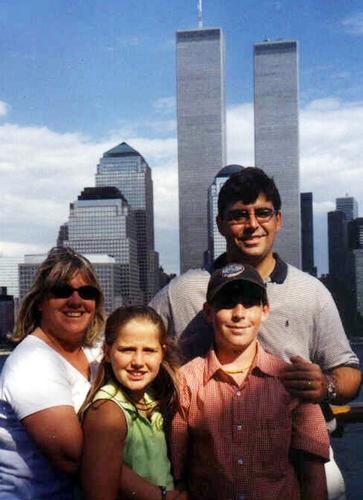

My father, John Robinson Lenoir, Vice President at Sandler O'Neill & Partners, who worked on the 104th floor of the World Trade Center's south tower, was dead. He was 38.

My story is simply one of thousands, and it is in resignation to the nature of narrative that I have focused solely on my own, rather than any conceit that my experience was somehow exceptional. I am simply one voice, the successor to the boy I was, who has somehow stumbled onto a soapbox.

One of the things I've grown used to since Sept. 11, 2001 is the utter cluelessness of anyone who tries to talk to me about it. While anyone who's been through a loss knows that the phrase "I know how you feel" is usually as insensitive as it is well meant, it's rare that one's personal business is so ingrained in popular culture and political rhetoric.

I've had people ask how I could possibly befriend a Muslim student, ending with, "You do know the A-Rabs killed your father, don't you?"

In middle school another student handed me a pin reading, "I bombed an Afghani child," as a gift, before patting me wordlessly on the shoulder.

I distinctly remember one boy who told me I should feel happy that "they're going to make 9/11 National Firefighters Day."

I'm not condemning the rather misguided attempts at consolation. I empathize with the underlying problem.

Though the national consensus is that 9/11 as an event changed everything, Americans don't know how to talk about Sept. 11 outside the narrative they've been provided.

The last known survivor of the Titanic died in 2009. (Bear with me for a second.) While the events of 9/11 and the sinking of the Titanic may not seem to share much at first glance, it is precisely on the surface that they come together. Both are admittedly tragic events that are so iconic that one only needs to see an unnamed image of the occurrence to immediately know what's being referenced. The New Yorker recently ran a cover of where the recent stock plunges were compared to a ship hitting an iceberg, with a group of fat, tuxedoed men sailing off safely in a lifeboat. Almost without realizing it, this real-world event has become an allegory, a cautionary tale of the mortal cost of greed, vanity and hubris. It's the sentiment everyone took away from the James Cameron blockbuster.

I have a recurrent daydream in which my child or grandchild asks me about Sept. 11, most likely for a school project, and I have to search for the right words to say. As a nation, we'll have to decide much sooner how we teach people about this event, as it increasingly sinks into the depths of history.

Ours is a nation divided -- not just by politics but by words. President Obama's reluctance to use the term "War on Terror" to describe our current entanglements in the Middle East has been just one cause for attack pitted against him by the far right. The story of 9/11 did not end this May with the assassination of Osama bin Laden. This story, my story and all our stories are one story. The narrative lives on in its retelling, and in the way it is woven into the fabric of American identity.

We praise New York firefighters for their bravery, rushing into the unknown at the risk of life and limb, and yet after 10 years we cannot give them what they deserve: acknowledgement that they were lied to about air quality dangers and coverage for their cancer treatment. We have rhetoric, we have fancy speeches and we have Hollywood blockbusters that tell us how to feel, but we must all search within ourselves to know the story as it happened and as it should be told.

Textbooks are being written, commemorative coins are being sold on TV, and The Huffington Post has repeatedly run stories about the rising generation for whom the events of 9/11 are as alien and fantastic as that luxury liner hitting an iceberg is for anyone born after 1912.

This Sept. 11, the memorial at ground zero is opening for the first time, and as a country we are no closer to agreeing upon what it is we want to remember.

We owe the dead, the suffering, the survivors and our posterity more than that. When my family and I join together this year to remember, I will pray again -- for the first time in 10 years -- not for my father but for those of us left behind. I will pray for our nation to heal, for the divisions to mend, and in the hope that one day, this day will have a message of hope.