This is Part 5 of the Timeline of Left Social and Political Art, 1989-2000. See Part 1, 1900-1944, Part 2, 1945-1966, and Part 3, 1967-1979, and Part 4, 1980-1989, on Huffington Post.

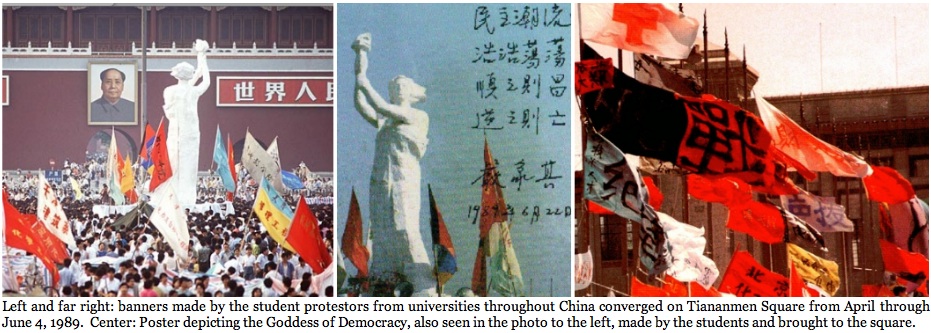

1989: If there is an art form we can glean from the many photographs and videos of the Tiananmen Square Demonstrations in 1989, it must be found in the multi-hued banners that converged on the Square and surrounding streets made by the students from different universities around China. Often their idiosyncratically-painted Chinese characters contrasted stylistically, yet intricately, to compose, as seen from a distance, rich textures of abstract gestural markings to the millions who watched around the world without more than a guess as to translations. They are best seen the nearer in date we come to the government's crackdown, such as on May 13, when the students began a hunger strike in anticipation of the highly-publicized state visit of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, which sent spontaneous crowds streaming in. Or when the government declared martial law on May 20th. It seemed that each new official call for the demonstrators and students to leave the square brought still more demonstrators and students, all unfurling wind-strewn banners and flags from newly energized ranks.

Surviving posters from the demonstrations or those that soon after sought to commemorate the protestors killed in the June 4th massacre and in the weeks following are few, but this one of the massive Goddess of Democracy statue that students assembled from polystyrene and paper-mâché and carried through the square has found it's way to the web. Quoting the Chinese political scientist and dissident, Yan Jiaqi, the poster reads, "The tide of democracy is powerful and mighty. Followers shall prosper, opposers shall perish. Yan Jiaqi, 6/22/1989."

Between April and June, 1989, the presence of a large Western press corps stayed the hand of the hardliners within the Chinese government from striking out at the student demonstrators assembled at Tiananmen Square and other locations around the country. But by June, Chairman Deng had deemed the events had reached a crisis point and Premier Li Peng persuaded the Politburo of clearing the counter revolutionaries not only from Tiananmen Square, but from the campuses throughout the provinces where they had gathered in support of the democratic movement. On June 2, hundreds of thousands of troops were dispatched to Beijing with live ammunition, many in tanks.

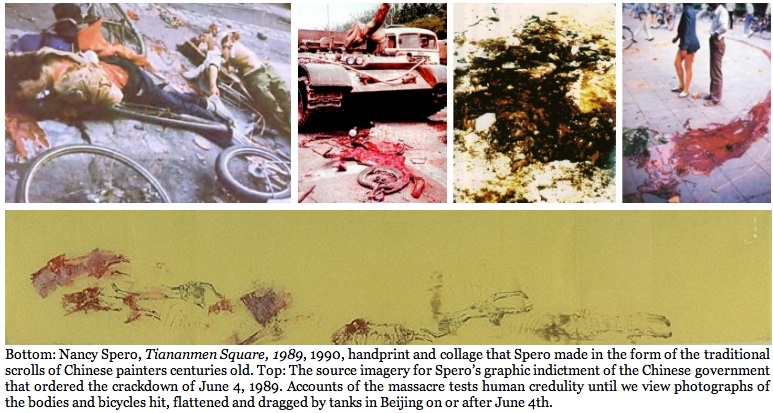

The hand-printed scroll made by Nancy Spero commemorating the lives lost in the crackdown on June 4 and thereafter seems unduly abstract to those of us who know her work. It is hard to make out just what is a human figure until we compare the scroll to photos of the crackdown's brutal efforts to end the insurrection. That's when we are hit with the horrifying reality in seeing that Spero hasn't made abstract markings. She has printed the bodies of the demonstrators as they appear in the photographs after the tanks of the people's liberation army literally crushed the demonstrators into the pavement. The scroll has been a medium of choice for Chinese painters for nearly two millennia, yet it is hard to imagine that any scroll before has signified human brutality and death so unflinchingly as Spero's rendering.

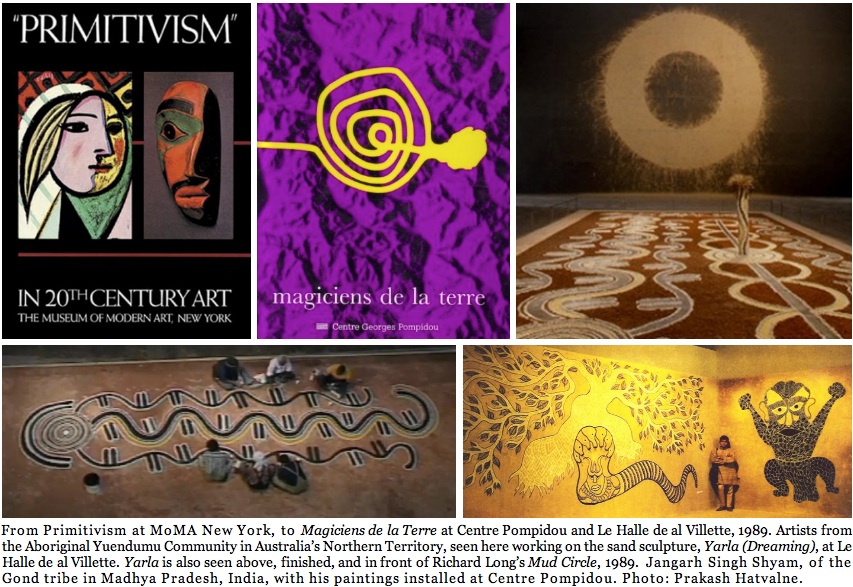

1989: Despite the controversy that surrounded the globally-encompassing exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth), it has weathered its shortcomings with an influence and legacy that secures its status as the first significant post-colonial global survey of art and aesthetics that sought, at least in terms of museum and exhibition practice, to reconcile the differences between indigenous productions and an encroaching homogenization of style and ideological relations to artistic production that we call modern and global. Although modeling the curatorial approach on the illusory polarity of self and other--with the self here standing in for the presiding Western model of ethnology--the curatorial team assembled under Jean-Hubert Martin adhered to a selection process that eschewed all colonial museological models that had dominated the Western exhibition and collection of the world's artistic productions as well as all classifications other than common formal, thematic, and contextual attributes, however slim.

In fact Magiciens de la Terre was mounted in reaction to a prior museum survey, the 1984 Primitivism show held at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1984. That show, organized by William Rubin, the museum's Director of Painting and Sculpture and Kirk Varnedoe of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, not only upheld the myth of cultural universality, it exalted the progressionist valuation of art that implicitly defined Modernism not just as one among many global standards of aesthetic taste, but as the culmination of all prior aesthetic systems--in short, an unspoken but no less salient vindication of ethnocentric and colonialist "centers" presiding over indigenous but "outmoded" margins of production.

The show would prove to be the pivotal point in the formation of a new globally-relevant criticism, and McEvilley would take the lead in reconfiguring this criticism with his Artforum article, "Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief." From McEvilley's point of view, "Primitivism was a banner exhibition for all the central premises of modernist Eurocentrism. It embodied the Kantian doctrine of universal quality; the Hegelian view that history is a narrative of Europeans leading the world toward spiritual realization; and the cartographic model of the West's centrality and the non-West at its margins. McEvilley would go on record as among the first art critics to denounce the practice of exhibiting and discussing non-Western production without naming the artists or dating the production and, when comparing it to Western art derived from tribal and other premodern sources, treating it as so many footnotes to modernist production, "illustrating something other than itself." This confrontation with the high church of modernism and one of the most powerful men in the artworld made McEvilley's new globalism something of a cause célèbre in the art world of the mid-1980s. It also made it a landmark article, the model for all future critques on Eurocentric practices in art history, curatorship, and art criticism.

Magiciens de la Terre tried to build on this new approach. The biggest change being that global diversity had come to largely replace the esteem of universality as a criterion for comparing and exhibiting art from different regions and periods in time. Globalism, in contrast to universalism, became seen as compelling cooperation and exchange from multiple sources (cultures, epochs, and geographies) without imposing any one as primary; it is the composition or network potentially encompassing all diversity without imposing unity or a singular or summarizing principle on it.

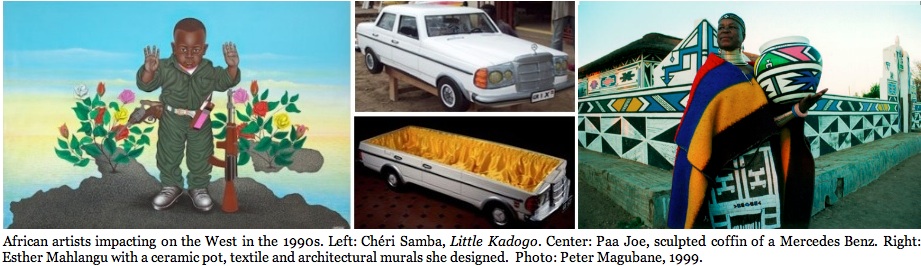

As with the Aboriginal artists of Australia and the Jain, Hindu and Muslim artists of India who advocate Indian aesthetics, African artists who either retain a strong indigenous identity or conflate their identities with Western styles of art and design have made significant inroads on Western art markets since Magiciens de la Terre (see above), despite the fickle tastes and trending of collectors.

One of those proven to have particularly lasting appeal to collectors in Europe and North America is the Congolese painter Chéri Samba, an unconventional figurative and political artist who believes that artists can have an influential role in shaping their society. Painting in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Samba incorporates aspects of comic art, billboard and sign painting in pointed commentaries about Congolese social and political life.

Ghanaian artist. Paa Joe is the foremost sculpted coffin maker of his generation. He is one of many Ghanan artists making coffins in the form of objects and living things, though those that having the broadest appeal in the West tend to be of modern commodities--cars, cell phones, cameras, computers. As novel as the concept is to non-Ghanans, in Ghana the custom is only the 20th century variation on a tradition stemming from the Ghana people's belief that people who die should be remembered for their achievements in life, in terms of profession, status, and favorite objects.

Since her Western debut in Magiciens de la Terre, Ndebele artist Esther Mahlangu has become world renown for her Ndebele painted and textile designs. Whereas Cheri Samba and Paa Joe have made the biggest impact on the art world, Mahlangu's extends far beyond, covering any and all sculptural, architectural and utilitarian forms that appeal to her and being sought after in all these markets.

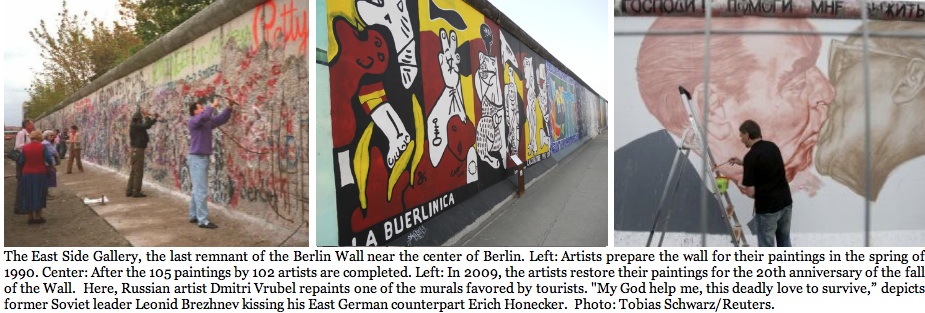

1989-90: "Berlin Wall: The date on which the Wall fell is considered to have been November, 9 1989, but the Wall was strategically made obsolete when after the border between Hungary and Austria was disabled the previous August, which led to an estimated 13,000 East German tourists escaping the East to Austria. Meanwhile, a wave of refugees found a way out via Czechoslovakia, then Hungary to Austria. As East Germans flooded the West German embassy, protest demonstrations broke out throughout East Germany in September 1989. By early November half a million people gathered at the Alexanderplatz demonstration in East Berlin. To ease tensions, General Secretary Egon Krenz provided safe passage to refugees at crossing points between East Germany and West Germany, including West Berlin, which became official and permanent.

In the weeks that followed, people came to the wall with sledgehammers and chisels to chip off souvenirs. One section of the wall that remains, located near the Berlin center on Mühlenstraße in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, was secured by The Künstlerinitiative (Artists Initiative) as a sector of the wall to be preserved and transformed into an open-air gallery. What became known as the East Side Gallery, likely the longest gallery in the world, has a length of 1.3km through Berlin and consists of 105 paintings by 102 artists from around the world. Painted in 1990, much of the art is populist and untrained, and by artists with very few connections to the artworld, which makes it all the more popular among the political middle classes. Although most of the art had to be restored in time for the 20th anniversary in 2009, the paintings are widely regarded as historically significant for expressing the euphoria and hope of a unified German people that saw itself ready to prove itself to be in league with the free world.

1989: Day Without Art began on December 1, 1989 as the national day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis. To make the public aware that AIDS can touch everyone, and inspire positive action, some 800 U.S. art and AIDS groups participated in the first Day Without Art, shutting down museums, sending staff to volunteer at AIDS services, or sponsoring special exhibitions of work about AIDS. Since then, Day Without Art has grown into a collaborative project in which an estimated 8,000 national and international museums, galleries, art centers, AIDS service organizations, libraries, high schools and colleges take part.

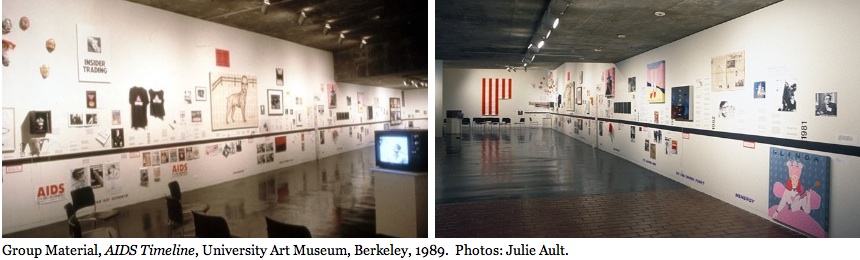

1989 was a good year for Group Material. They completed a series of year-long presentations centered on the theme of Democracy at The Dia Foundation for Art in New York. In Berlin, they presented AIDS & Democracy at the Neue Gesellschaft fur Bildende Kunst. And they installed the project for which they remain most widely recognized, The AIDS Timeline, at the University Art Museum, Berkeley.

By this time the collective had been comprised of many artists and art administrators, the most well known including Tim Rollins, Julie Ault, Doug Ashford and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Among the many collectives issuing from new York, their installations stood out for not being known for their visual aura as much as for their textual density. This aspect of compiling images, objects, and readings as if all coalesced into one text was most successful when employed in their timelines installed in galleries. It also served the collective well in achieving their mission, which they've stated to be the movement of "the idea of art from isolated models of refinement to a self-consciously political and cultural approach to communication. As the interface between subject matter and society, presentation space was adopted as a significant artistic medium, removing the distinction between artists and curators. Moreover, the status of presentation space itself as a standard of access to information was opened beyond the museum and gallery to engage the public through storefronts, talks, town meetings, newspaper ads, magazines, bus posters, etc."

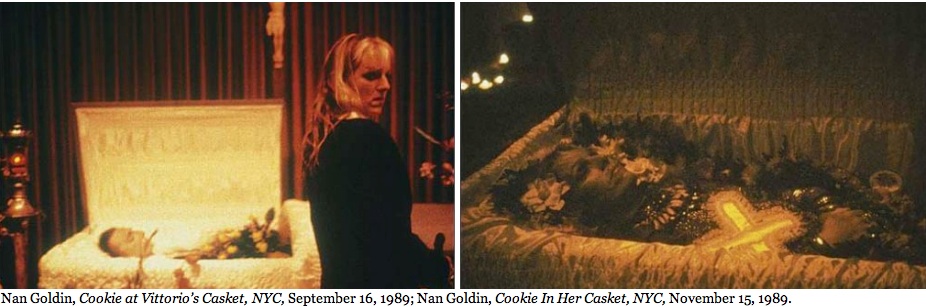

From its introduction in the art world, Nan Goldin's art became something of a chronicler of the New York underground. She filled a void that opened in art photography with the death of Diane Arbus, except that Arbus was something of a tourist in the world of the recalcitrant nonconformist, the self-stylized freak and the misfit. Goldin lived the life she photographed. Her "subjects," which strike some audiences as eccentric, self-possessed, willfully retreating into the wounds of cultural injury, are to Goldin beloved lovers and friends. In this respect Goldin was made political at least at the outset only because the friends in her life unknowingly thrust the power of art into her hands, through her camera, into her brain, where the force of it all must have been anything but chosen.

It was through her friends that Goldin became a most unwilling chronicler of the early spread of AIDS. As Goldin wrote in "20 Years: Aids & Photography" for The Digital Journalist, "AIDS changed everything in my life. There's life before AIDS, and after AIDS... We were in Fire Island that first time we'd heard about AIDS, in July of 1981. I was with Cookie Mueller, Cookie's lover, Sharon, and photographer David Armstrong, one of my oldest, best friends, and 2 or 3 other boys. Cookie used to write a monthly art critique for Details Magazine. She was the starlet of the Lower East Side: a poetess, a short-story writer, she starred in John Waters's early movies. She was sort of the queen of the whole downtown social scene."

Of the many she photographed in their last stretch of life, Cookie Mueller was the most famous. A writer with a tres hip cult following, she became a muse to Goldin, in that she crafted a portal of words onto the wild world that was New York, in her case in the 1970s. "I didn't think of them as people with AIDS," Goldin writes. "About '85, I realized that many of the people around me were positive... At that stage, we still didn't know very much. There was a lot of ignorance. We were very obsessed with what caused it: There were all kinds of rumors, everything from amyl nitrate to bacon. People were tested and being told they had something called ARC, that quickly became medically non-relevant. I was in denial that people were going to die. I thought people could beat it. And then people started dying."

Here Goldin photographed the wakes of Mueller's husband, Vittorio, whom she married only a few months before, and then the wake of Mueller, again within the space of mere weeks.

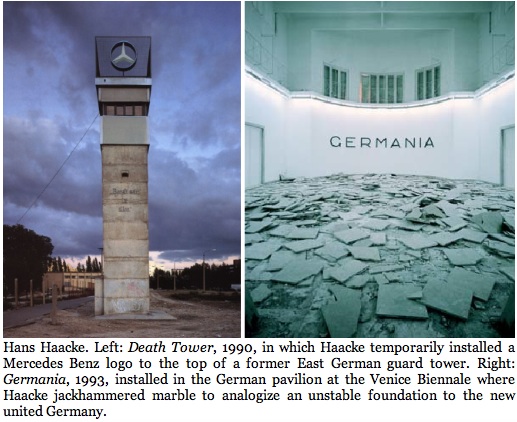

1990-1993: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Hans Haacke returned to his native Germany in 1990, and to the site of the former wall that had long seemed to divide the entire world into two political polarities. There he found a former guard tower from which snipers shot at East Germans fleeing to the West. In a work called "Death Tower," Haacke affixed a Mercedes Benz logo at the top. Haacke's ideological point: that corporations target and constrain lives in the same way that dictatorships do.

At the 1993 Venice Biennale, Haacke's entry in the German Pavilion was an epic production called Germania. In place of a stable floor, Haacke jackhammered marble into fragments which the viewer had to walk precariously over. On a prominent, curved wall, the name "GERMANIA" was inscribed theatrically in a classical invocation of myths of the past. A viewers walked through the pavilion, the shifting marble was amplified by loudspeakers, imparting a sense of tectonic shifts that imparted analogy to the historic shifts undergoing the German people as a result of a unification many did not welcome. Haacke's analogous work was anything but subtle in its implication that the "German Question" that the National Socialists under Hitler had asked, and that had been asked by the Imperial German powers in the centuries preceding, was still being decided as unification confronted a generation upon whom the newly unified German government placed severe restrictions in granting citizenship only for those who could prove their legacy of German blood.

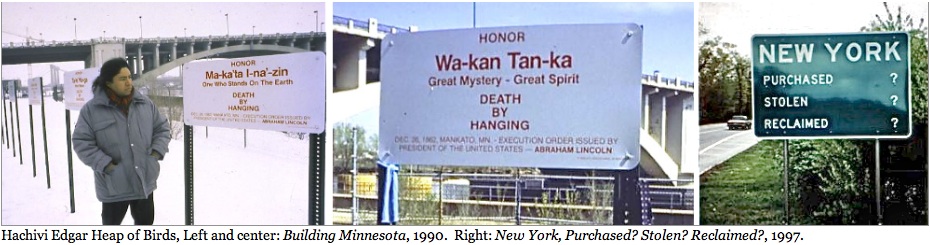

1990: The Walker Art Center commissioned Hachivi Edgar Heap of Birds' Building Minnesota (1990), a signage installation mounted on the banks of the Mississippi River in Minneapolic, Minnesota. "Heap of Birds set forty large, metal, billboard-like signs along Minneapolis's downtown riverfront. The signs honored the forty Dakota men who were sentenced to death by Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Jackson after the US-Dakota Conflict of 1862, in what is the largest mass execution in American history." (Walker Art Center.)

In New York: Purchased? Stolen? Reclaimed?, Heap of Birds offers us an explicit assertion of indigenous geography by inserting historical and spatial indicators as substitutes for road distance indicators. The first two refer to history. The third to the refusal of the native peoples to concede the loss of their lands.

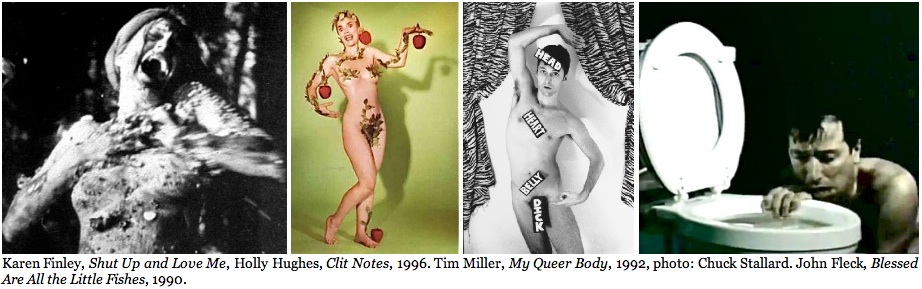

1990: Four National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grants awarded to performance artists by the NEA peer review panel were vetoed by NEA Director John Frohnmayer in June,1990. The four artists were singled out because of their sexual preferences and political discourses. Three of the rejected artists, Holly Hughes, Tim Miller and John Fleck, are gay and deal with homosexual issues in their work; the fourth, Karen Finley, is an outspoken feminist. The endowment had been under attack since 1989 for funding supposedly "lewd" work, and it became known that the four rejected artists have continually been singled out by conservatives in the past. The NEA claimed that the artists' work violated an anti-obscenity pledge which each grant applicant was required to sign in order to receive funds.

In 1993, all members of the NEA Four received compensation surpassing their grant amounts in 1993 when courts ruled in support of the four artists. But the damage had already been done, as many in Congress now found it acceptable to challenge the funding of art based on the so-called moral content. Since then the debate that has come to be known as the culture wars dividing up the issues of funding and art have hardened into two entrenched camps, each demonizing the other.

Karen Finley, meanwhile, sought a higher ruling against the restrictions of content as a violation of free speech and on the use of NEA funds and definitions for "obscenity." On June 25, 1998, eight years after the Frohnmayer veto, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling upholding a "Congressional decency test" for awarding federal grants to artists. The high court requires the National Endowment for the Arts to take into account "general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public" in awarding grants. The only dissenting opinion in the 8-1 decision came from Justice David H. Souter who said that this law violated the First Amendment. The Clinton Justice Department argued in favor of the censorship provision. As a result of this case and others in lower courts, the NEA abolished all grants to individual artists.

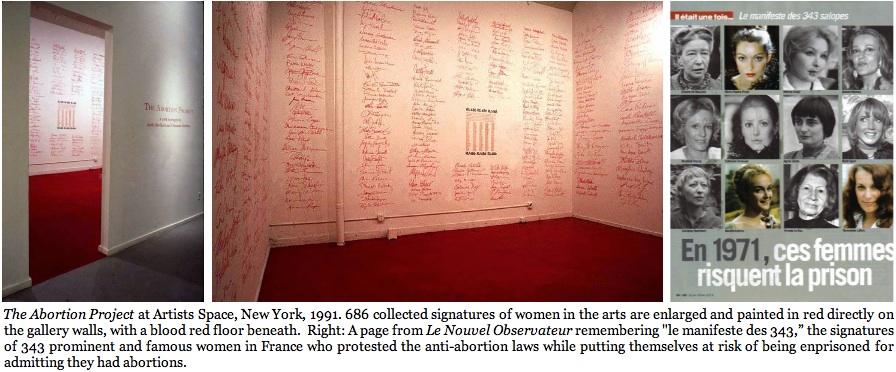

On January 17, 1991, the day that Operation Desert Storm began in the first Iraq War, The Abortion Project opened at Artists Space in New York. The collaboration between New York artists Kathe Burkhart and Chrysanne Stathacos, and further organized by Real Art Ways curator Anne R. Pasternak, the exhibit is an installation commemorating the 20th anniversary of the "Manifeste de 343," a French public declaration in 1971 stating all the signatories had had abortions, the most celebrated of whom included Simone de Beauvoir, Catherine Deneuve, Marguerite Duras, Gisèle Halimi, Bernadette Lafont, Françoise Sagan, Agnès Varda, Jeanne Moreau, Brigitte Bardot, and scores of other prominent women in the arts. That manifesto opens with the lines, "One million women in France have an abortion every year. Condemned to secrecy, they have them in dangerous conditions when this procedure, performed under medical supervision, is one of the simplest. These women are veiled in silence. I declare that I am one of them. I have had an abortion. Just as we demand free access to birth control, we demand the freedom to have an abortion.

"The Abortion Project doubled the Manifeste's number, collecting 686 signatures of women in the arts, which was enlarged and painted in red directly on the gallery walls. The second part of the exhibit consists of artworks by 40 women artists who have long been involved with issues of gender and women's rights that had been shown at Simon Watson Gallery, in New York. They included Barbara Kruger, Adrian Piper, Lorna Simpson, Kiki Smith and Nancy Spero. The third part of the show featured "The Abortion Project Anthology," a publication featuring the work of women poets, artists and writers, including Laura Cottingham, Eileen Miles, Jill Rappaport, Kaye Rosen, Christine Sanders and Lynne Tillman. Besides Artists Space and Real Artways, the Abortion Project was also installed at New Langton Arts, San Francisco, CA, and at Hallwalls, Buffalo, NY, where it stirred considerable controversy with the city's conservative press and the religious right.

1991: The collective of queer women artists known as Fierce Pussy is formed to bring lesbian identity and visibility into AIDS activism and street demonstrations throughout the 1990s. Although composed of successive waves of lesbian activists, Nancy Brooks Brody, Joy Episalla, Zoe Leonard, and Carrie Yamaoka have made up the core membership.

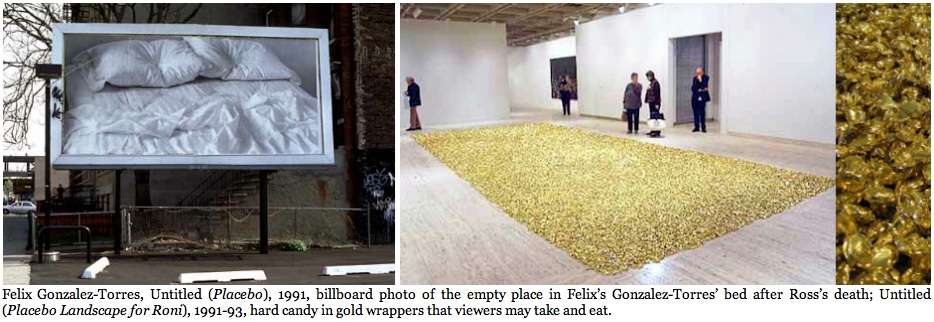

1991-1993: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the conceptual sculptor who in January 1996 died of AIDS at age 38, combined his personal experiences with public conceptual art installations. In one exhibit, he piled wrapped candy in a corner and invited viewers to take one, replenished from an "endless supply," an idyllic sentiment exemplary of a desire for heaven on earth. Yet his art is anything but sentimental. His billboard installations of the early 1990s displaying the photographic images of his empty bed are simple facts of loss as much as they are tributes to his lover lost to AIDS in a public gesture that directs his grief into the collective that receives all private life events as political motivations and ends. In some of Gonzalez-Torres' minimalist candy installations the weight of the candy is to equal his lover's weight, other's his own weight, and still others the weight of both men combined. In the above installation, the candy is to be maintained at 1200 pounds.

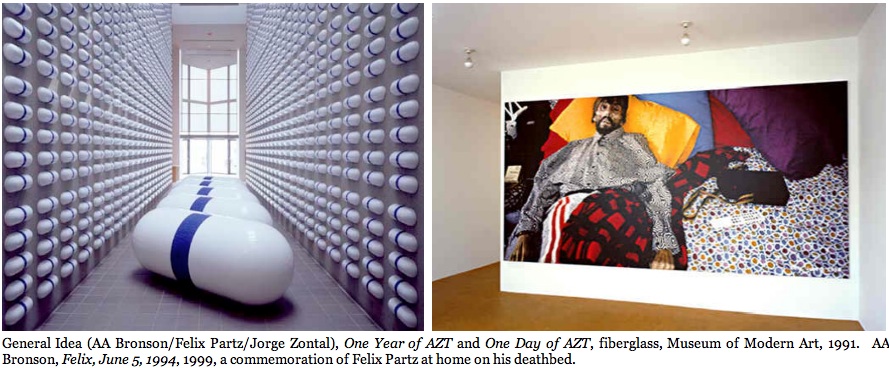

1991-1995: General Idea, the trio of artists whose queer art has been internationally exhibited since the early 1970s, would become decimated by the HIV virus, with two of its members, Jorge Zontel and Felix Partz, dying only months apart from each other in 1995. Surviving member, AA Bronson, has since gone on to make an art of post-science shamanism geared for a generation seeking a healing that science has so far shown itself incapable of supplying. (See more about General Idea and their iconic AIDS art in Part 4, When the Personal Is Made Political: Left Political Art Timeline, 1980-1989.)

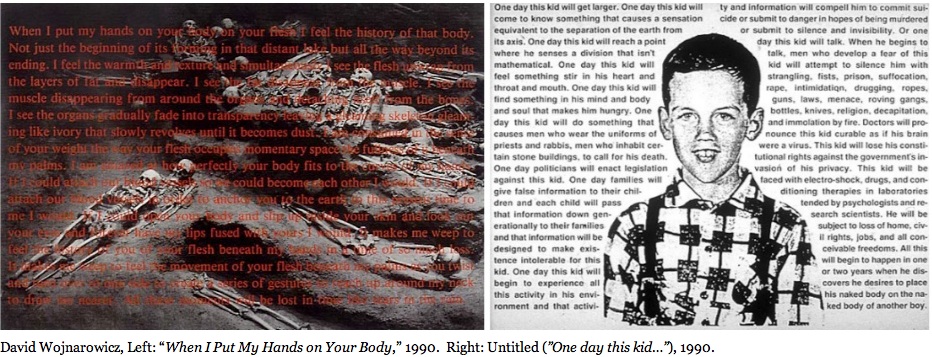

1992: Artist and writer David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related causes. Although feminists in the 1970s had widely disseminated the notion of the person being political, as late as the mid 1980s, few male artists, gay or straight, made his personal life the center of his work as acutely and ultimately as tragically as had David Wojnarowicz. Then, too, it appears that Wojnarowicz's work from the very beginning emerged directly from his personal experience. He claimed that he didn't study art history, didn't go to college, and he was begrudged for not being an art world networker. And so he made his art about the things he knew: his boyhood; his sexuality; life on the street; and witnessing his body as it progressively fell victim to the HIV virus. A prolific and impassioned writer, the text of his art work, When I Put My Hands On Your Body, overlain the image of excavated graves, speaks as freshly these years after his death as when he wrote them.

"When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending. I feel the warmth and texture and simultaneously I see the flesh unwrap from the layers of fat and disappear. I see the fat disappear from the muscle. I see the muscle disappearing from around the organs and detaching itself from the bones. I see the organs gradually fade into transparency leaving a gloaming skeleton gleaming like ivory that slowly revolves until it becomes dust. I am consumed in the sense of your weight the way your flesh occupies momentary space the fullness of it beneath my palms. I am amazed at how perfectly your body fits to the curves of my hands. If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time to me I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath my palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain."

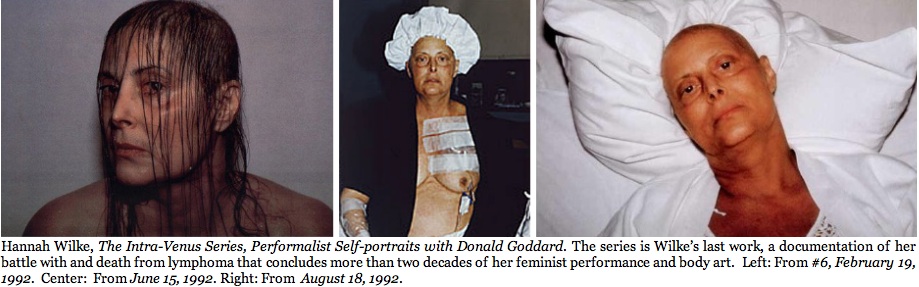

1992-1993: After being diagnosed with lymphoma, Hanah Wilke took to documenting her treatment of the disease and ultimately her death. Called the INTRA-VENUS series, Wilke created a monument that speaks for more than the feminism she for twenty years had represented with her art. Each successive photo and video makes it increasingly obvious that Wilke defied the societal convention of dying silently and away from view. She ignored the pity, disgust, and sentimentalism that so many people attach to death and dying, just as she refused misery and bitterness to overwhelm her life's work's. All this is the Personal is Political taken to its culmination. As did Camus in his writing, Wilke took a stand on death by imposing on it her choice of making death part of her art. This is a political act as much as it is for many a spiritual act, or just a living act. Wilke died on January 28, 1993. During the later stages of her illness, she collaborated with her husband, Donald Goddard, on a series of photographs documenting the realities of her physical and mental transformation.

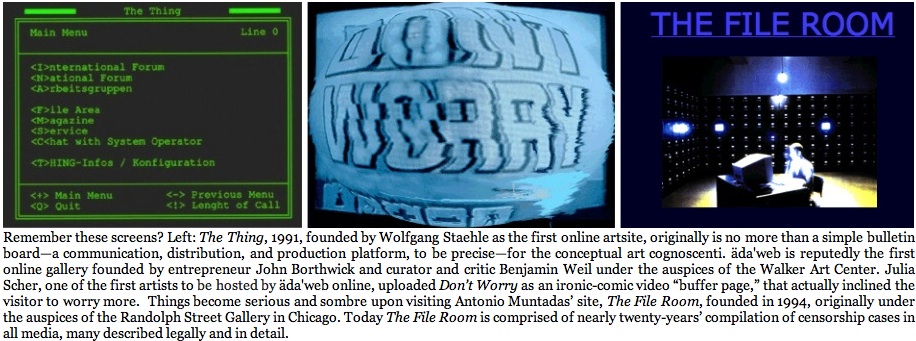

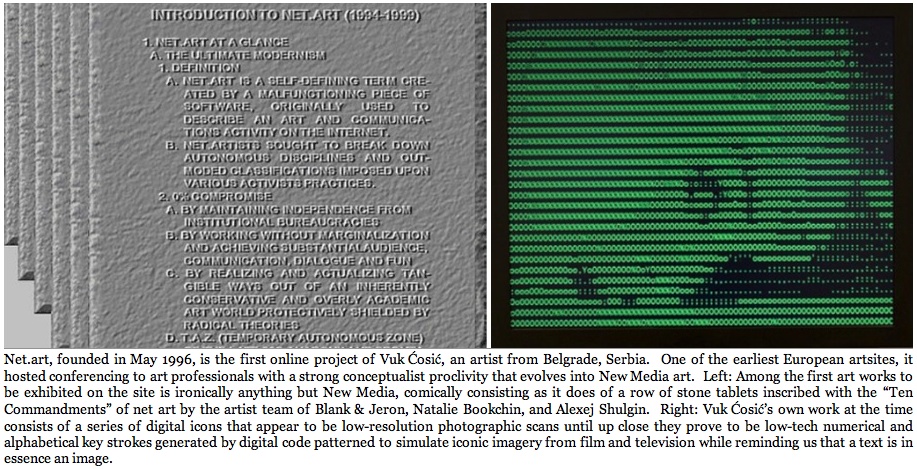

Consensus has it that the artist Wolfgang Staehle was the first net host to sponsor an artsite online when he founded The Thing in 1991 in New York. Although it's capacity was limited to that of a bulletin board system (BBS), Staehle had a vision that the net would become something of a production, conferencing, and distribution platform for artists and art cognoscenti--in essence a net art world for the conceptual artist. He went on to establish The Thing Cologne in 1992, and The Thing Vienna in 1993. From there, other artists and curators entered the art net frey as the net became increasingly capacious. äda'web, curated by Benjamin Weil, went online in 1994, as did Plexus under Stephen Pusey's administration, Antonio Muntadas' comprehensive online archive of censorship cases known as The File Room and net.art, which under Vuk Ćosić became a hub for European artists, also appeared in 1994.

New technologies invariably renew utopian yearnings. Politically, the artist versed in institutional critique saw in the net the capacity to outmaneuver the gallery system, to eliminate the middle man---the curator and gallery dealer. Access was the dream that suddenly seemed attainable. As with any new technology, expectations ran high. With artists' entry to the internet and later the world wide web, art wouldn't only reach its democratic apogee in terms of production and distribution. Art would become nomadically composed and predisposed with the aid of a technology of unlimited data retrieval and sharing that reflects the human neurological system and its cognitive functions. Allowing us to randomly roam from conceptual model to conceptual model--say between the visual and the textual, the personal and the public, the rational and the poetic. As a result we adapt more quickly to diversity and change, become expert at identifying, even understanding interpretations not initially our own, and look forward to their surprises rather than react defensively to differences. All of which is to say that artists saw the net as affording a world of models--concepts and imagery--with which s/he can become a world communicator, negotiator, peace maker, for having the capacity of building bridges between people's diverse values and experiences.

Unfortunately, what most of the administrators of these sites hadn't fathomed was how to generate income while still adhering to their political ideals, which is why so many online galleries came and went and the real world art market is more prodigiously profitable than ever. To be continued.

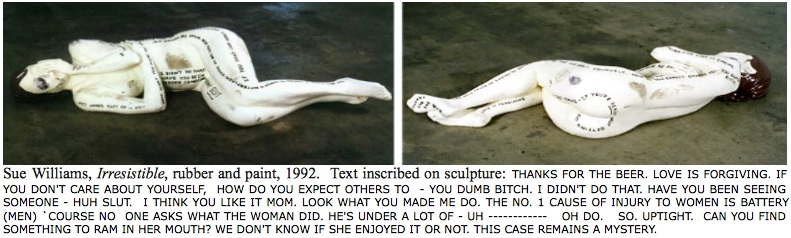

1992: Sue Williams' show at 303 Gallery was something of a watershed for women's art in representing her own personal experience of violent abuse. Few prior representations of battered women were as frank, graphic, biting and politically energizing as this show, which gave other women who had similar experiences incentive to make their own art of release. (See my feature, From Victim to Victor: Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out on Huffington Post.)

Alfredo Jaar's Geography = War, 1991, is a large installation. Duratrans, light boxes, fifty-five- gallon metal barrels and water in a dark room illuminate images of war that set the scene for work that speaks directly to the viewer's conscience.

The work consists of fifty-five gallon barrels filled with water, over which are suspended light boxes with photographs of the citizens of Koko. The photographs are seen by viewing the reflections in the water-filled barrels. As the viewer peers into the barrels to see the photographs, he or she also sees his or her own reflection. Jaar seems to be asking each of us to confront our own role in societal injustices. The light boxes are like those used for advertisements in hotels, train stations, and airports. Usually, such displays advertise goods to be consumed; here, they present people living in the direst circumstances. Jaar deploys such reversals to make the viewer aware of his or her own position as a citizen of the world.

Jaar has stated: Africa and Latin America are rapidly becoming the dumping grounds for millions of tons of toxic industrial waste from the so-called "developed" countries. . . . Some of the world's poorest nations have been targeted as potential dumpsites for US and European waste. . . Forced to choose between poison and poverty, some are choosing the poison, which will bring them "incomes" sometimes larger than their annual gross national product. . . .

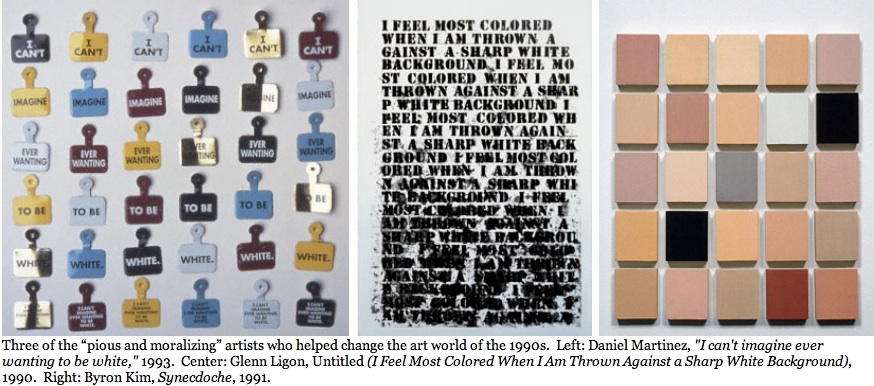

1993: It doubtful that there has ever been a Whitney Biennial that received a more unanmious barrage of negative criticism from the press than the Biennial of 1993. That no doubt is because it is the only biennial to have openly and flagrantly disinterred all the racial, ethnic and sexual stereotypes ever espoused by white supremacy. It should come as no surprise that many of the white critics of both sexes were incensed in having a mirror forced before them, while showing little if any cognizance that their complaints signified a desire to suppress the expressed experience of the women, queers, transgendered, and people of color whose art, until the 1990s, was rarely if ever represented in the museums, blue chip galleries, and trade journals from which the elite art world is comprised.

The negative response ranged from the irrational: a critic called the radically daring exhibition "dazed recognition of the degree to which artistic conservatism had gripped the museum." The critic didn't bother explaining how exhibiting a new art that made its legacy of suppression a medium to be altered, and that had never been explored thematically or formalistically by a prior museum, was artistic conservatism. A prominent magazine delivered called the Biennial "A Fiesta of Whining," a slur aimed at the tropical peoples of the biennial as surely as a reprimand for not forgetting that the artists' ancestors were raped by their owners, or were purposely given blankets with small pox so to eradicate their race. Clearly the said critic considered his own grievance of being shaken out of his cultural amnesia the only thing worth whining about.

One newspaper critic called the art by people who have historically been denied access to cultural institutions, "a pious, often arid show that frequently substitutes didactic moralizing for genuine visual communication." Yes, when people endure murder, poverty, apartheid in the name of racial, religious, or ideological supremacy, they are apt to turn both pious and moralizing--especially considering that it is the surpremacists who have made "genuine visual communication" impossible. "Pious" and "moralizing" are words that make me think of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Desmond Tutu. For that matter, many of Goya's, David's, Delacroix's and Picasso's gracing the museum's halls are moralizing--without the self-deprecating humor of the biennialists.

One trade journal critic didn't even bother to pass her writing as criticism, so contemptuous and smug was its assumption of privilege and entitlement in commenting that she couldn't think of cultural genocide when all she could think about was in what good shape a certain performance artist kept herself. Clearly the reviewer forgot that slaves endured labor and Native Americans' closeness to nature, which often made them far stronger--and potentially more dangerous--than the ruling classes.

In the end David Ross and the curators, Elisabeth Sussman, John G. Hanhardt, Thelma Golden, and Lisa Phillips, got their revenge, as it turned out that the 1993 Biennial must have had one of the highest returns in terms of subsequent artist success. The great majority of them went on to make significant historical, monetary and institutional gains for the art expressive of the politics of feminism, ethnicity, sexuality and gender. Whether or not the impact would or would not have been made without the 1993 Biennial, the fact is the art world is a substantially more inclusive place because of the very artists who were scolded for being too aggressive in their artistic activism.

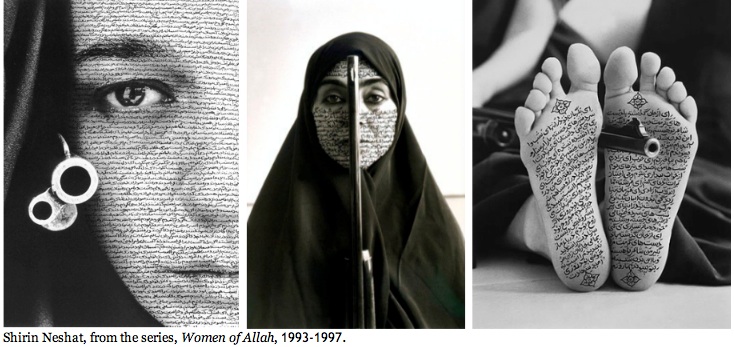

1993-1995 Provocatively inviting misinterpretation in a society prone to Islamophobia, Shirin Neshat's Women of Allah series, in which several shots are of Iranian women covered by chadors under the Muslim law of hijab and holding guns that for many Western viewers reinforce the image of hostility we carry with us since 9/11. Which is why it is important to point out that these images were made six, seven, eight years before 9/11.

Then what are they about? Explicitly, they commemoration the Iranian women who fought in the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988. Implicitly, they reflect the social codes that compel us to conform to traditions we would rather do without. Neshat's art exhibits many of the codes governing women's homosocial dress and behavior depicted in the centuries-old Islamic miniatures of women's eyes peering out from recessed lambrequins and tightly-wrapped veils. The guns were an early ploy of Neshat's to impart an aura of strength and resilience on her women. She later learned that more subtle signs impart even more strength and resilience, though without the dramatic signification. Such as the sight of Muslim women who band together to contend with male imperatives buttressed by writ of law. It is through Neshat's work that we begin to realize that what appears to be a divide of civilizations rasped out by religious difference is more deeply a variation in the degrees to which two different cultures enforce the male legislation of gender and sexuality.

1994 was the year that four politically radical New York exhibitions by four of New York's most radically innovative exhibition organizers made the world's most jaded audience for art sit up and take notice--if not take notes.

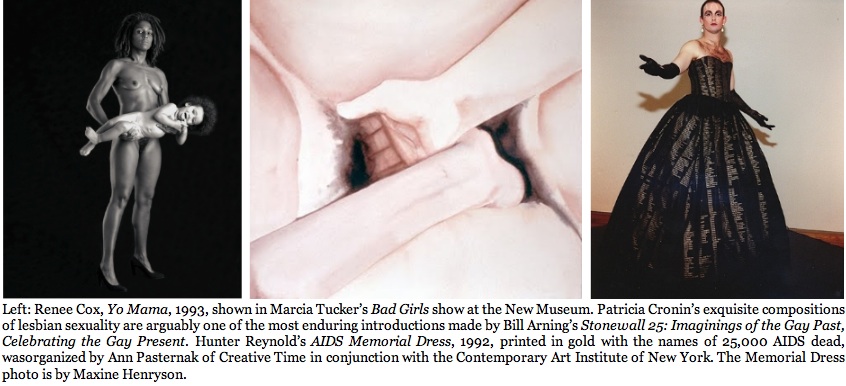

Bad Girls, curated by Marcia Tucker at the New Museum, presented work by over 60 visual, performance and media artists dealing with feminist gender issues in ways that are both humorous and distinctly transgressive. Rumors of feminism's death in the mainstream press prompted Tucker to search out younger women artists for whom feminist issues are paramount particularly "those defying the conventions and proprieties of traditional femininity to define themselves according to their own terms, their own pleasures, their own interests, in their own way," but also in a way that involves, Tucker continues, "a delicious and outrageous sense of humor to make sure not only that everyone gets it, but to really give it to them as well."

Stonewall 25: Imaginings of the Gay Past, Celebrating the Gay Present, organized by Bill Arning at White Columns has been called by many who had seen it the best queer group show ever shown in New York. Situated just a few blocks from the original Stonewall Inn, the White columns space was amply filled with a grouping of work that shouldn't have worked, given the seemingly arbitrary selection and spatial arrangements and relationships, yet it did work precisely because of the idiosyncrasies of seeing historic queer celebrity and literary photos and porn alongside objects fussily concerned with their own artful presentation. As for those historical items, Arning pointedly uses them to bring attention to the successive generations of American queers by marking out what we share, what we don't, and what part of the collective past filters down to form our tastes and proclivities. Arning himself wrote about the generational pairings, that the new generation of queers "look back on the Stonewall and pre-Stonewall eras with romantic nostalgia...This, generation while still active in ACT-UP, Queer Nation, and WAC, still feels a sense of sorrow at not knowing what it was like to be there that night at the first moments of revolution when the legendary (possibly apocryphal) fed-up drag queen threw the first bottle at a cop."

Ann Pasternak had only just begun her long tenure as the Director of Creative Time in New York the year that she bravely co-sponsored Hunter Reynolds: Patina Du Prey's Memorial Dress, a healing ritual and performance sculpture. I say brave, because in writing the affair sounds potentially offensive, introducing the signage of a drag queen--which to many viewers brings with it the image of outrageous disregard for convention--at a function demanding propriety out of respect for the dead and their grieving survivors. In fact, Reynolds ensures that there is not only no glimmer of camp, irony, or humor breaking through the spectacle of a large balding man wearing a classically handsome black bell dress while rotating on a dais for the audience's riveted inspection. It's the stillness and the silence of the gallery's numerous and lingering visitors that encourages our silence, then directs our eyes onto the names of the then 25,000 AIDS dead printed exquisitely in gold and undulating in and around the dress's sumptuous folds. The atmosphere not only cultivates respect, but signals that, regardless of the dress, this is no ordinary drag queen taken to the stage. Reynolds is in fact invoking the history of the healing shaman ritual in which the tribal shaman, usually a man, dons the traditional clothing of the tribe's women to summon a power ascribed in the society to women alone, yet which becomes more concentrated when the conduit of the power passed to him is male. Perhaps because it is an acknowledgement too esoteric to be understood in the modern context it is presented, Reynolds has seen to it that the bodice of the strapless dress is cut for a male torso. It takes some time to notice the difference, but it no less discretely registers on our mind's eye until it dawns on us that, besides the absence of a wig, the artist declines to simulate cleavage. The overall effect is provocative not so much for the negation of stereotypes, but for the many enigmas bestowing an aura of mystery and awe onto this angel of deathly benevolence.

(Commentary on the fourth resounding show of 1994 follows the two images below.)

1994: Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, curated by Thelma Golden at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

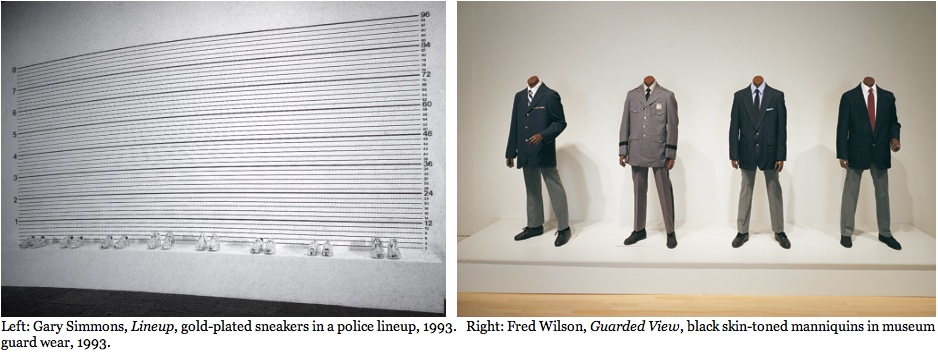

Considering the the black male as an icon brings with it an array of negative stereotypes that many of us would rather forget, Thelma Golden would prefer that we remember them so to put them permanently to rest. The more renown works include Robert Colescott's painting "George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page From American History," depicting the subject surrounded by stereotypical figures including Aunt Jemima and the Cream of Wheat man. One of Gary Simmons' best installations, "Lineup," situated several gold-plated sneakers in a police lineup, while another favorite, Fred Wilson's biting installation of black male mannequins in the uniforms of museum guards draws a good deal of attention. And for good reason. Wilson is asking us why the only black personnel seen in museums are the guards.

Surprisingly, the most negative response to the show was from black audiences who want to see blacks portrayed positively in art. In one interview, Golden let down her guard to show her exasperation: "I have said this about 4 million times. This show is not representation. This is not a documentary survey on black men as they live and breathe today, it is not a catalogue of types. It is about the way in which contemporary artists have looked at black masculinity, especially how it has been portrayed in popular culture. My role in it was to talk about how truly obsessed America is with race, if we really get down to it. And if we get down to it, it is not really race, it is black masculinity--that's what it is. They are synonyms, in a weird way."

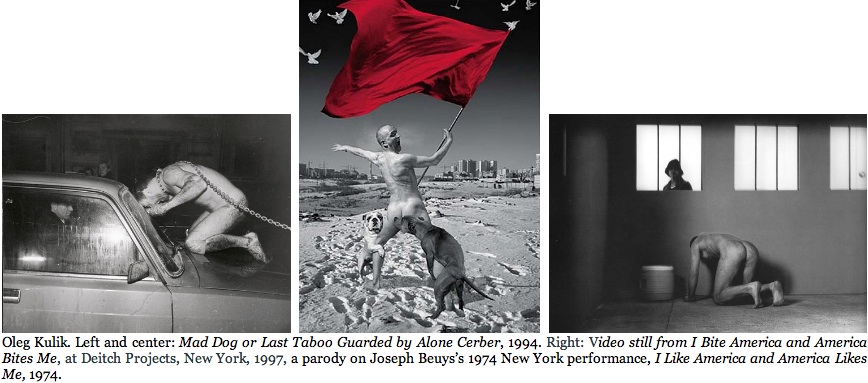

1993-97: Glasnost and Perestroika were Russian words that circulated throughout the media in the second half of the 1980s for representing the new Soviet policy under Mikhail Gorbachev calling for increased openness and transparency (glasnost) in government institutions and activities, and the reduction of corruption (perestroika) among communist party officials. With less censorship and greater freedom of information, artists flourished under the new reforms, which expanded at least for the 1990s with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The near official gouge of the new policies being tried came in the personage of Oleg Kulik, an artist who in the 1990s became best known for living performances as a human dog who, having escaped from his leash, defecates in museums and bites people. Many of Kulik's commentators have interpreted his performances Mad Dog and Reservoir Dog to be metaphors for Russia, a country that, as the critic Max Seddon describes it, is "naked, poor, something to be feared, a product of the unbridgeable conflict between West and wild East." Philospher and critic Boris Groys likens Kulik's clown-like behavior to the Futurists in possessing no fear of looking laughable, which is the quality necessary to becoming emancipated from the heavy seriousness of contemporary art and its authorities. But there apparently is also a zoocentric impetus, one in which animals play no mere supporting role.

In April 1997, Kulik inhabited New York's Deitch Projects space, or more accurately, a heavily-secured dog house built in the space. Entitled I Bite America and America Bites Me, the performance was an unsubtle parody of I Like America and America Likes Me, the now iconic performance work made by Joseph Beuys in New York some twenty-two years earlier, and in which he inhabited the space for three days with a live coyote. Only now Kulik plays the part of the canine. There was nothing comic or ironic about the performance, with many visitors finding it unsettling how like a dog Kulik becomes. The artist has gone on record commenting on his belief that humans are not the center of the biosphere, nor do they control it. He would like to see humankind regard itself in its proper perspective as equal with animals, not lords to them. It's a philosophy that puts his performances as a bird, a fish and a bull, in perspective. It seems that Kulik believes that 'true democracy' cannot be had without true participation from animals and plants. Before writing him off as a loon, we might recall that Leonardo da Vinci in his notebooks proposed something similar.

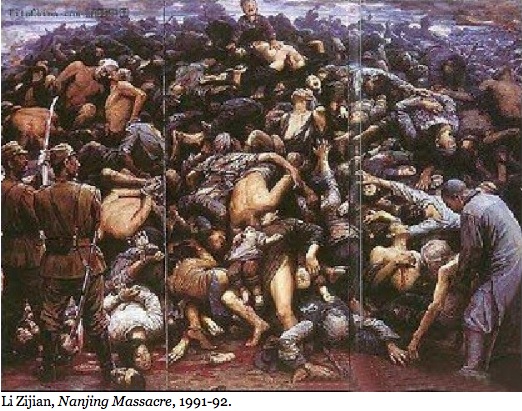

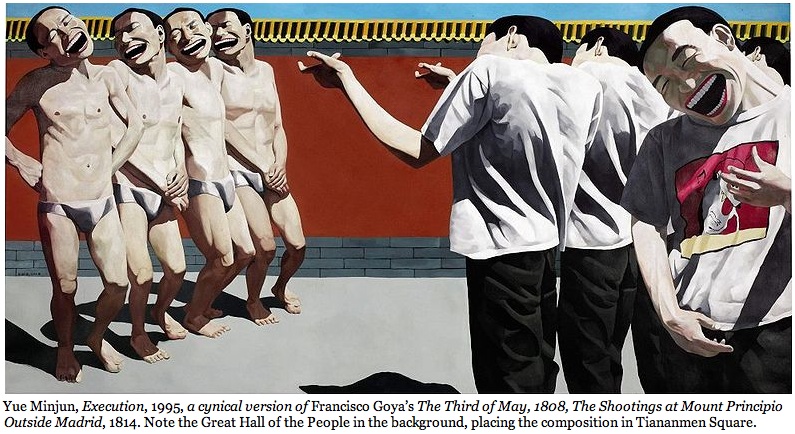

To have once been a nation with great utopian aspirations only to then find them dashed by the obscenely insane pogroms of megalomaniacal dictators against tens of millions of their own people time and again, can only lead to two character responses: heroic action and apathetic cynicism. In June 1989 the world watched the heroism of the Chinese people quashed by brutal militarism openly and defiantly on our televisions, leaving us only to imagine what brutalities transpire behind closed doors. Since then, Chinese artists, both those living abroad and within the mainland nation, have reacted to the massacre of 1989 in varied ways, the extremes of which are embodied by the painters Li Zijian and Yue Minjun.

Although Li Zijian is a US-based artist, his larger audience is Chinese, who better appreciate his Buddhist themes of humanity and compassion, which many Westerners find to be too sentimental, while eschewing his N.C. Wyeth-like style. But the painting that has energized people of all walks is his history painting of the Nanjing Massacre. I should say, all walks except some Japanese audiences, who refuse to acknowledge the veracity of the history depicted. (Read about the suppression of the Japanese propaganda paintings made during the Sino-Japanese war in my Political Art Timeline, 1945-1966: Postwar Art of the Left on Huffington Post.) The history the rest of the world remembers is one of Japanese armies invading the Nanjing province of China on December 13, 1937, and throughout its six-month occupation, Japanese soldiers began a massive campaign of rape and murder called variously the Rape of Nanjing or the Great Nanjing Massacre. Within six months, between 200,000 to 300,000 Chinese people were slaughtered.

Li never brought up the Tiananmen Square Massacre or analogized the Nanjing Massacre with it, but since Li met the Buddhist monk Xing Yun, he traveled with the financial and spiritual support of the master through China, where it was within his interests to also garner the government's support of his project. The timing of Li's sudden enlightenment near immediately after the Tiananamen Square events, coupled with the fact that Li emigrated to the U.S. after his father was inprisoned for political reasons, has given some (including myself) to see in his work an obvious correlation between the 1937 and the 1989 massacres.

Yue Minjun's painting have been called light hearted by his gallery's PR. I think they're quite sinister. Not sinister in terms of the artist's inner personality revealing itself, but as a commentary on the cynicism that fills many otherwise decent Chinese citizens as a result of their seven decades under autocratic rule. Cynicism seems especially the resort of people that find that capitalism without democracy has virtually become state policy. And as Yue's paintings exemplify, if capitalism with democracy as we know it is sedative, then capitalism without civil rights must be narcotically delusional.

What else could Yue's re-signification of Goya's masterpiece of the The Third of May, 1808 mean, what with it re-enacted with a cloned doppelgang replete with locked grins. Grins under democratic capitalism signify selling out, but grins in autocratic capitalism signify emptying out--spiritually, socially, politically. Of course I exaggerate to make my point, which is precisely what Yue does. Private lives hold secret moments of redemption. But to hold onto hopes for democracy under hardline murderers means to live as hostage -- something Yue couldn't paint and live to be free about it. And so he paints hostages. And what do hostages do when being observed by their captors? Exactly what Yue's dopplegang does -- smile in excess. As with all behaviors, desperation has a code. In Yue's work, the code can be deciphered with the key of context, which in Yue's paintings are encoded by location, many of them well known. Where is the lampoon transpiring. Who or what is being mocked. Yet to decode their encoded message, we need to remember that Yue's paintings are not really lampoons, not really mockeries. They are a nation held hostage, which means they mean exactly the opposite of what they seem.

1995: On the occasion of the Third International Women's Conference in Beijing, Ann Pasternak of Creative Time co-published, and Robin Kahn edited, Time Capsule: A Concise Encyclopedia by Women Artists, with introductions by Kathy Acker and Avital Ronell, and contributions by more than 500 women artists from the world over, including Kenya, the Czech Republic, Russia, and Cuba. (Creative Time and SOS International, New York, 1995).

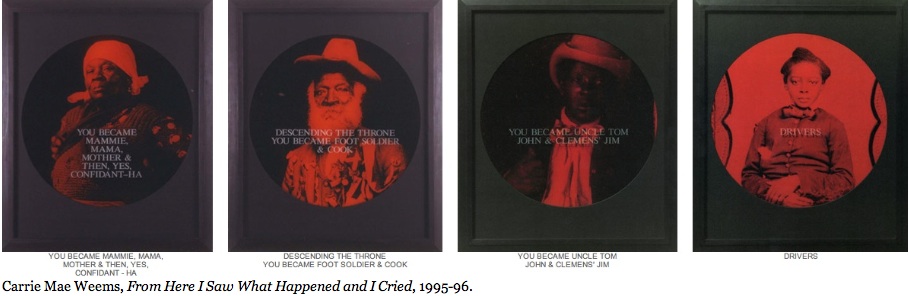

1995-1996: Artists of color have used art for recording histories of colonialism, slavery, the Civil Rights struggles, and various injustices delivered their peoples for the better part of the 20th century. It's just that white audiences until recently never bothered to look. Which is why, when the arbiters of "high" culture chose to finally open the doors of the visual arts to artists of color in the 1990s, many were taken aback by the critiques of the history of white oppression and patronage they were confronted with. Among the more direct and powerful of these critiques came from Carrie Mae Weems. Since Weems, like David Wojnarowicz, works with image and text combined, her work best represents itself. The text here accompanied the wall installation Weems called, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, made between 1995-1996, and comprised of 33 crimson-toned prints of African Americans appropriated from a century of photography and public media.

FROM HERE I SAW WHAT HAPPENED: YOU BECAME A SCIENTIFIC PROFILE, A NEGROID TYPE, AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL DEBATE & A PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT. YOU BECAME MAMMIE, MAMA, MOTHER & THEN, YES, CONFIDANT - HA. DESCENDING THE THRONE YOU BECAME FOOT SOLDIER & COOK YOU BECAME UNCLE TOM, JOHN & CLEMENS' JIM, DRIVERS, RIDERS & MEN OF LETTERS. YOU BECAME A WHISPER, A SYMBOL OF A MIGHTY VOYAGE & BY THE SWEAT OF YOUR BROW YOU LABOURED FOR SELF, FAMILY & OTHERS. FOR YOUR NAMES YOU TOOK HOPE & HUMBLE. BLACK AND TANNED, YOUR WHIPPED WIND OF CHANGE HOWLED LOW, BLOWING ITSELF - HA - SMACK INTO THE MIDDLE OF ELLINGTON'S ORCHESTRA. BILLIE HEARD IT TOO & CRIED STRANGE FRUIT TEARS, BORN WITH A VEIL YOU BECAME ROOT WORKER, JUJU MAMA, VOODOO QUEEN, HOODOO DOCTOR. SOME SAID YOU WERE THE SPITTING IMAGE OF EVIL. YOU BECAME PLAYMATE TO THE PATRIARCH AND THEIR DAUGHTER. YOU BECAME AN ACCOMPLICE OUT OF DEEP RIVERS. MIXED-MATCHED MULATTOS, A VARIETY OF TYPES MIND YOU - HA. SPRANG UP EVERYWHERE. YOUR RESISTANCE WAS FOUND IN THE FOOD YOU PLACED ON THE MASTER'S TABLE - HA. YOU BECAME THE JOKER'S JOKE & ANYTHING BUT WHAT YOU WERE-HA. SOME LAUGHED LONG & HARD & LOUD. OTHERS SAID "ONLY THING A NIGGAH COULD DO WAS SHINE MY SHOES." YOU BECAME BOOTS, SPADES & COONS, RESTLESS AFTER THE LONGEST WINTER, YOU MARCHED & MARCHED & MARCHED. IN YOUR SING SONG PRAYER YOU ASKED, DIDN'T MY LORD DELIVER DANIEL? FROM HERE I SAW WHAT HAPPENED. AND I CRIED.

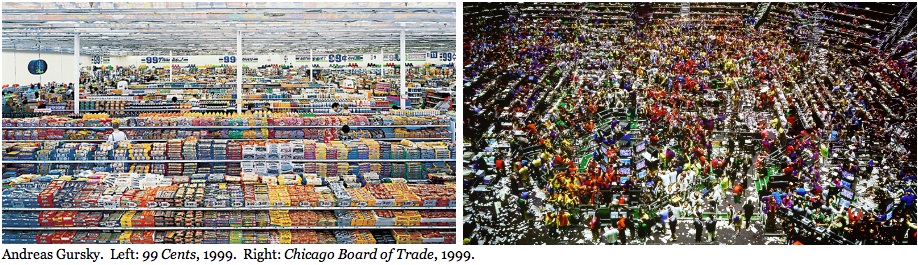

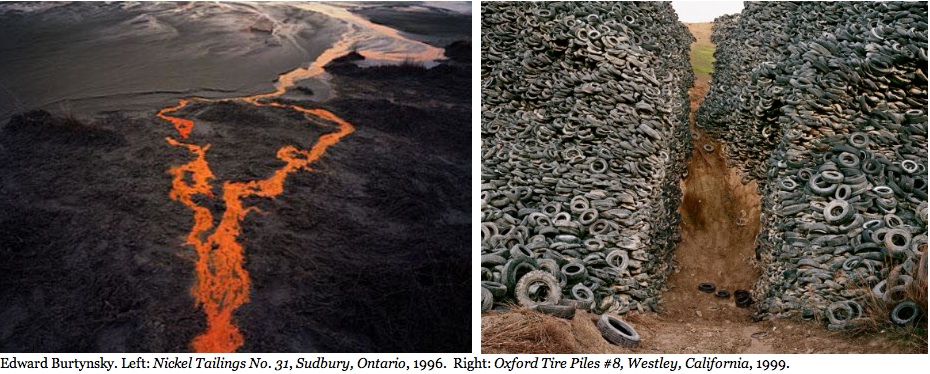

German photographer Andreas Gursky and Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky have revived the credence of the notion that aesthetics and politics can be conjoined in the same visual and ideological spaces by providing cautionary photographic narrations on the state of human over indulgance in industry and consumption of both commercial and natural goods.

For Gursky, the emphasis is placed on the individual lost within the richest mine of signs and signifiers, models and mythologies, history has ever produced. Corporate culture has seized hold of the signage, manufacturing, infrastructure and superstructure with the aid of populist and elitist iconography alike. While paying specific attention to the imagery and texts, media and ambience launched by advertisers, urban planners, architecture firms, news networks, financial marketers, and politicians, Gursky rigorously catalogues the overarching barrage f rom the vantage of the panoramic scope or wide-angled lens that in his hands iconically reifies the collectivity of the corporate mythos, ethos, and agora.

But whereas Gursky renders the post-industrial landscape, Edward Burtynsky's series of manufactured landscapes takes on an almost primitive approach to the industrial landscape, revealing that the industrial age is still vital, just made invisible to the more affluent and middle-class. In cataloguing the hidden epicenters of industrial production and waste of quarries, recycling yards, factories, mines, ship breaking, and oil fields, Burtynsky enables our cognition of the human environmental imprint at the same time that he strikes down the myth that a postindustrial corporate class has become more important than the labor force that keeps the modern world supplied with the energy and commodities it demands. In so doing, he projects a romantic yearning for a return to a nurturing pre-industrial nature at the same time he seemingly pulls out that dream from under us by showing us landscapes so scarred by industrial and consumer waste that the recovery of nature even in the absence of humans would take millennia.

Together the two artists chart out a scenario whereby overlapping industrial and postindustrial visions challenge our more basic preindustrial needs and desires. It's enough to revive the discourse and grand narrative of alienation for any attentive individual.

2000-2001: Oliviero Toscani the creative mind behind the controversial ad campaigns that turned Italian clothing maker Benetton into a household name have a tendency to aim for the jugular. Toscani worked as Benetton's creative director for 18 years, from 1982 through to 2000. Among the shock ads he engineered count the ad that the company calls Pieta. Printed in 1991, it depicts the family of the dying AIDS activist, David Kirby, surrounded by his family at his hospital bed. In 1991 the impact of AIDS in the West was taking its worst toll. Customers and vendors alike were scandalized. Many stores refused to stock Benetton that season.

A later ad depicted the clothes of a dead Bosnian soldier--the clothes he was killed in, to be specific. The garments, a pair of blood-stained trousers with a camouflage pattern and a blood stained T-shirt, are laid out flat across the picture. The T-shirt has a bullet hole at the level of the ribs. At the top of the advertisement is a text in Serbo Croatian. At the bottom left, the words "United Colours of Benetton" are written in larger green letters.

But Toscani will likely be best remembered for the headline-grabbing 2000 campaign using photos of some 26 death row inmates from six U.S. states. Toscani and Benetton say the international "We On Death Row" campaign was aimed at drawing attention to the controversy surrounding the use of capital punishment in the U.S., where support for the death penalty is nearly as universal as opposition to it is in Toscani's native Italy. The furor over the campaign in effect ended Toscani's association with Benetton.

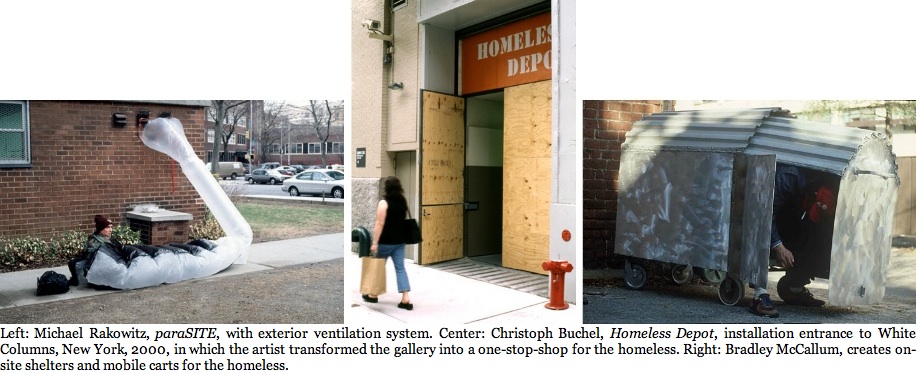

2000 White Columns' director Paul Ha curated Concerted Compassionism, which presented the work of three artists who addressed the problem of homelessness.

Michael Rakowitz, in an ongoing project he calls paraSITEs, presented a series of exterior ventilation systems installed on existing architecture structures providing heat for the homeless. At the time of the White Columns show, Rakowitz had built and distributed 30 such paraSITEs to homeless people in Boston, Cambridge, MA, and New York City.

Swiss artist, Christoph Buchel's Homeless Depot installation transformed the White Columns gallery into a one-stop-shop for the homeless. Although the exterior punningly riffs off the Home Depot brand name, inside Bushel genuinely stocked items freely given to the homeless upon their request, and which he states include models for shelters, money-earning aids, and objects for entertainment.

Bradley McCallum presented documentation of his on-site shelters and mobile carts for the homeless which he had been designing and distributing in Richmond, VA, according to the needs of the specific user. His homeless recipients are thereby equipped to collect aluminum cans, bottles, and other materials for recycling income. All carts remain the sole property of the individuals who require them, which in McCallum's artistic vision resonates as a sustained visible and political presence in the cities hosting them.

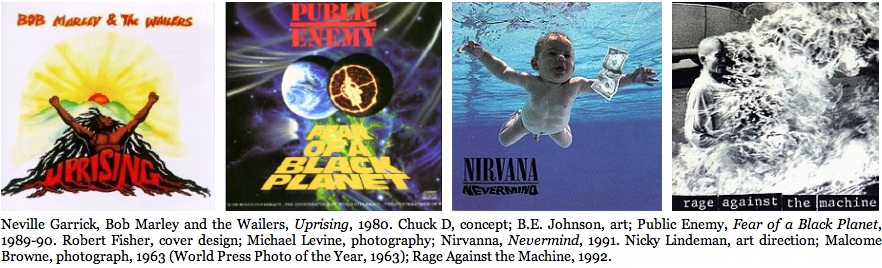

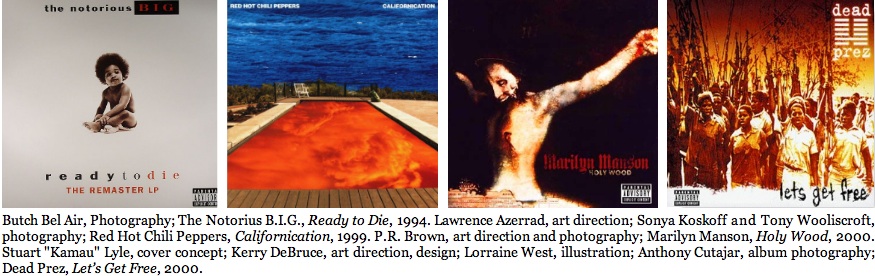

1980-2000. Since the 1960s, the covers of music discs, and by 2000 the online download promotional icon, is the first and often the most indelible political signage encountered by young audiences. Although mainstream music studios largely suppressed political music in the 1980s until it proved commercially profitable in the Capitalist recycling bin, smaller independent music venues kept alternate political music alive, until, in the 1990s, Grunge, Rap, and some alternate Rock again infused the mainstream with the sounds and visions of politically-minded artist-activists.

Next: Nomads Occupy the Global Village: Left Political Art Timeline, 2001-2012. May Day on Huffington Post.

On 4/19/12 the Walker Art Center credit was added to the entry on Edgar Heap of Birds, which the author mistakenly omitted.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.