"Let's see if I can get us killed," Sebastian Thrun advises me in a Germanic baritone as we shoot south onto the 101 in his silver Nissan Leaf. Thrun, who pioneered the self-driving car, cuts across two lanes of traffic, then jerks into a third, threading the car into a sliver of space between an eighteen-wheeler and a sedan. Thrun seems determined to halve the normally eleven minute commute from the Palo Alto headquarters of Udacity, the online university he oversees, to Google X, the secretive Google research lab he co-founded and leads.

He's also keen to demonstrate the urgency of replacing human drivers with the autonomous automobiles he's engineered.

"Would a self-driving car let us do this?" I ask, as mounting G-forces press me back into my seat.

"No," Thrun answers. "A self-driving car would be much more careful."

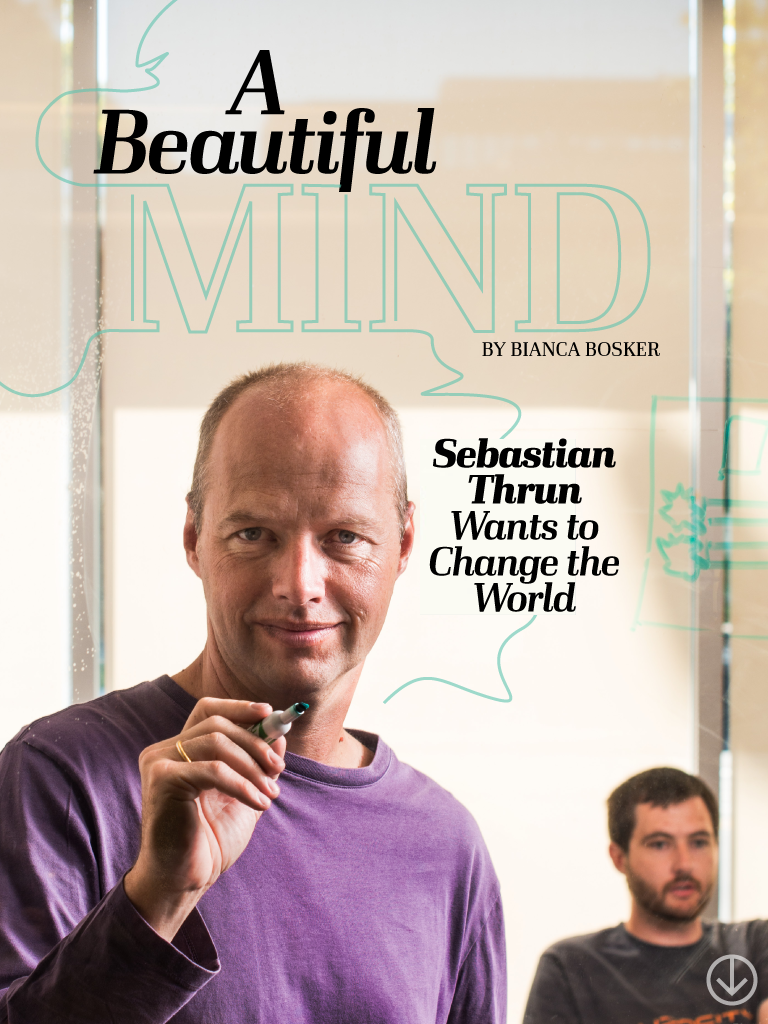

Thrun, 45, is tall, tanned and toned from weekends biking and skiing at his Lake Tahoe home. More surfer than scientist, he smiles frequently and radiates serenity—until he slams on his brakes at the sight of a cop idling in a speed trap at the side of the highway. Something heavy thumps against the seat behind us and when Thrun opens the trunk moments later, he discovers that three sheets of glass he’s been shuttling around have shattered.

Once we reach Google X, he regains his stride, leaving me trotting by his side as he racewalks to his office. Motion is a constant in his life. A pair of black roller skates sit by his desk. Twelve years ago, he borrowed his wife’s sneakers to run the Pittsburg marathon, without bothering to train for the race. He got his son on skis before most other kids his age got out of diapers.

When Thrun finds something he wants to do or, better yet, something that is “broken,” it drives him “nuts” and, he says, he becomes “obsessed” with fixing it.

Over the last 17 years, Thrun has been the author of, or a pivotal force behind, a list of solutions to a entire roster of “broken” things, making him a folk hero of sorts among Silicon Valley innovators, though hardly a household name elsewhere. While he’s in a hurry in almost every other aspect of his life, he embraces a slow-cooking approach to invention and product-building that sets him apart from many of the create-it-fund-it-and-flip-it whiz kids and veterans who populate the Valley.

Thrun’s resume is populated with seismic efforts, either those already set in motion or others just around the corner. There are various robotic self-navigating vehicles that guide tourists through museums, explore abandoned mines, and assist the elderly. There is the utopian self-driving car that promises to relieve humanity from the tedium of commuting while helping reduce emissions, gridlock, and deaths caused by driver error. There are the “magic” Google Glasses that allow wearers to instantly share what they see, as they are seeing it, with anyone anywhere in the world—with the blink of an eye. And there is the free online university Udacity, a potentially game-changing educational effort that, if Thrun has his way, will level the playing field for learners of all stripes.

“While everyone is running around saying ‘I’m going to do a better mobile photo thing so I can defeat Facebook and suck out more of their market cap to me,’ Sebastian is going around saying, ‘I think driving is totally screwed up and there should be autonomous cars,’” says venture capitalist George Zachary, an investor in Udacity. “He thinks much more boldly about the problems.”Other observers say all of this is firmly in the tradition of the best sort of innovators.

“What’s unique about Sebastian, and all innovators, perhaps, is that they don’t start with the current situation and try to make incrementally better based on what’s been done in the past. They look out and say, ‘Given the current state of technology, what can I do radically differently to make a discontinuity—not an incremental change, but put us in a different place?’” says Dean Kamen, the inventor of the Segway. “He is a true innovator…And he has a fantastic vision.”

Many Silicon Valley standouts have succeeded by making radical improvements to products that already exist. Facebook, for example, did social networking better than any of its predecessors. Smartphones were around well before the iPhone, but Apple came up with a gadget far slicker than the competition.

Thrun likes creating new things from scratch and invents for a world that should be, for an audience that may not yet be out there, for conditions that may never be met. “I have a strong disrespect for authority and for rules,” he says. “Including gravity. Gravity sucks.”

To that end, and for all of his bravado, Thrun also says that he distrusts even his own beliefs and theories, calling them “traps” that might ensnare him in a solution based more on his own ego than logic.

“Every time I act on a fear, I feel disappointed in myself. I have a lot of fear. If I can quit all fear in my life and all guilt, then I tend to be much, much more living up to my standards,” Thrun says. “I’ve never seen a person fail if they didn’t fear failure.”

Thrun imagines a future where cars fly, news articles are tailored to the time you have to read them, and teachers are as famous and well-paid as Hollywood celebrities. He grouses that we don’t wear devices to monitor our health twenty-four-seven instead of relying on symptoms to diagnose what ails us. He can spot inefficiencies everywhere he turns, and in most cases, sees technology as the magic bullet.

When he talks about his mission to “look for areas that are just intolerably broken where even small amounts of technology can yield a fundamental sea change,” Thrun makes it clear that his goal isn’t to make us high-tech, but to make us high-human.

“I have a really deep belief that we create technologies to empower ourselves. We’ve invented a lot of technology that just makes us all faster and better and I’m generally a big fan of this,” Thrun says. “I just want to make sure that this technology stays subservient to people. People are the number one entity there is on this planet.”Simple and Streamlined

Though Thrun says his adult life revolves around trying to find ways that technology can help people, his childhood and adolescence were mainly about self-help. The youngest of three children, Thrun was born in 1967 in Solingen, Germany. His parents, devout Catholics, told him he was an unplanned baby. Thrun recalls having little contact with his parents, and especially his father. His siblings “required a lot of attention and there was almost no attention left for me,” he says.

His father was a construction company executive and more often than not his first order of business was disciplining Sebastian or his one of siblings with a beating, at the request of his wife. Thrun says his stay-at-home mom was “heavy into punishing people and sins and all that stuff.”

Thrun responded by retreating into a solo world of calculators, computers and code.

“I reacted a lot by just insulating myself from this and so mentally, emotionally I wasn’t that connected,” he says. “I learned to basically pull my own weight, just do my own thing. I spent a lot of time alone and I loved it. It was actually really great because to the present day I love spending time alone. I go bicycling alone, go climbing alone and I just love being with myself and observing myself and learning something.”

Thrun befriended an inventor in his neighborhood who gave him spare parts and a soldering iron, then let him tinker. As an eight-year-old, he’d come home from school, shut himself up in his room, turn on Pink Floyd, AC/DC, Mozart, or Bach, and spend hours sitting on his bed programming his Texas Instruments TI-57 calculator to solve math problems and play games (These days you can find him blasting a mix of classical concertos and Rihanna).

The calculator had no memory, of course, so every time he switched it off, he lost all his code. Eventually, he graduated from his calculator to a display model computer at the local department store, but basically, he was still dealing with the same problem: after four or five hours building games on the store machine, he’d be kicked out and all his work vanished. He took this inconvenience as a challenge to perfect his code so that he could re-enter it in the fewest possible steps. This fastidious dedication to simple, streamlined programming stayed with him, and he would later require his students to write straightforward, elegant code.

When not sitting at a screen, Thrun sang in a five-person choir with Petra Dierkes, a girl two years his junior who would become his girlfriend when he was 18, and, eventually, his wife and colleague at Stanford University. He also played the piano, improvising his own songs as a way to study and express his emotions.

Thrun was a gifted student and terrible pupil with a self-imposed homework ban that lasted from seventh grade through high school graduation. In college, the unprecedented freedom to choose his own coursework sparked a newfound passion for his academic work. He combined a major in computer science with an unorthodox double minor in medicine and economics, a combination that would eventually help him design a “nursebot” to assist elderly patients. When he graduated from the University of Bonn with a Ph. D. in computer science and statistics in 1995, he leaped at the chance to join the faculty at Carnegie Mellon University—what then seemed like “paradise” to Thrun—and spent eight years there before moving to Stanford, where he was computer science guru.

Out in the Valley, Thrun struck up an acquaintanceship with Google co-founder Larry Page, who asked him to see a robot Page had built in his spare time. The two men met for dinner at a casual Japanese restaurant in Palo Alto and Thrun returned to Page’s house to see his creation. The robot’s hardware was in decent shape, but Page “got stuck on the software side of it,” according to Thrun’s diagnosis. He borrowed the robot, flew in a few friends, and returned Page’s bot within a day after giving it the ability to localize itself. After another two or three days of work, the robot could navigate. Thrun said Page was “blown away.”

In 2005, Thrun’s engineering team at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory built a driverless car, a blue Volkswagen Touareg SUV named Stanley, that managed to navigate 132 miles of desert terrain on its own, becoming the first self-driving car in history to win the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Grand Challenge — a race through the sands of Nevada organized by the United States Department of Defense. The previous year, not a single one of the 15 entries from some of the most powerful robotics engineers in the world had managed to complete more than eight miles of the course. Thrun won the first year he competed, just 15 months after deciding to enter the race.

Page, who professes self-driving cars have “been a passion of mine for years,” watched Stanley’s triumph in the Mojave desert. Soon after, Google hired Thrun to sire the sons of Stanley. In 2010, Thrun helped Page and Sergey Brin, Google’s other co-founder, launch Google X, a top-secret and closely-guarded lab that the search giant tasked with making the impossible possible. The following year, Thrun relinquished his tenure at Stanford.

Xtreme engineering

Google X’s engineers are housed in a low structure covered in squares of dark, mirrored glass that offer a mercury-tinted reflection of the parking lot, bikes and trees that surround it. There are jails less secure than this research lab. Employees need a key card to unlock the entrance, and then are admitted to a small waiting area furnished with two chairs and a foosball table. From there, employees must swipe their badges again to enter any of the labs within, each door plastered with signs warning Googlers to stay vigilant of “tailgaters.”

For a visitor, it’s like stepping into the labs of a mad, hipster scientist. Floors are made of concrete, wires hang from ceiling, tubing covered in foil gleams from the rafters and row after row of black metal desks fill the wide-open space. Thrun’s desk stands in the center of a vast space, at the end of a long row of identical workstations. His is tidy and spare, save for a nametag, an unopened cardboard box, a DVD about the DARPA Grand Challenge, a white Japanese humanoid robot and The Idea Factory, Jon Gertner’s history of Bell Labs—AT&T’s legendary innovations incubator that won seven Nobel prizes and helped usher in the information age.

Thrun says he rarely reads books (they’re “too long”), but Gertner’s tome is particularly fitting in a place that aspires to be the heir to the Bell Labs throne. Its mission, according to Thrun, is to work on areas of innovation that have “hard scientific challenges” and “can influence society in a massive way.” Thrun had considered working with the government to deploy self-driving technology to help soldiers in the field, but the military’s stipulation that he not publish his results killed the collaboration. He instead brought his autonomous vehicles to Google, where they provided the inspiration for Google X and, in Thrun’s view, would get the support they needed to “impact large, large numbers of people.”

Thrun crouches down to strap on his roller skates, but is distracted by a Google X-branded skateboard produced by a colleague. He grabs the board and starts wheeling around the room.

“Sergey fell on this? Awesome,” Thrun remarks with a smile on his second lap. The cavernous area, nearly empty at 9 a.m., echoes with his chirps — “Aah!” “Whee!”— as he loops the room, narrowly missing the edges of the desks, bookcases and fridges stocked with free food.

“Don’t fall, we need you,” a Googler shouts at Thrun.

A fascination with images as facilitator for human relationships infused Thrun’s work on Google Street View, which allows people to digitally meander the streets of Mumbai, trace a nature hike in Yosemite, or tour New York’s Times Square—all from the comfort of their homes. In 2007, Google acquired mapping technology which Thrun’s team at Stanford had developed to train Stanley—technology Thrun nearly used to start his own company, Vutool.

Page tasked Thrun with applying the software to scaling Google Street View as quickly as possible.“I always felt that if countries knew each other better, there would be less war,” says Thrun. “Often conflict goes with demonizing other countries and cultures. I figured if we could bridge the gap between cultures with images, that would not be a bad thing to do.”

Two years ago, Thrun assembled a team of Google X engineers and tasked them with another assignment, one also rooted in the future: to reinvent the computer.

The result is Project Glass, a.k.a. Google Glasses, an endeavor Thrun makes a point of asking me to note is now being led by his colleague Babak Parviz. Thrun hands me a pair of the “glasses,” which will be available for $1500 to a limited group of tech industry insiders in early 2013. Worn like a pair of lens-less spectacles, the device suspends a glass cube around half an inch wide just far enough to the right of my retina that I can still make direct eye contact with Thrun, who all but hovers with excitement in the chair across from mine.

A video of fireworks begins to play on the cube and the screen glows purple, pink and blue, both from my vantage point and Thrun’s. A faint soundtrack of the explosions hums from a speaker just above my ear. The image on the glass shifts as I tilt my chin and move my gaze, and without realizing it, I snap a picture of Thrun. A small row of icons appears with the option to share it.

Google Glasses’ creators have taken pains to design a device that won’t isolate people from their surroundings. For example, the speaker sits above the wearer’s ear, not in it, and the cube rests above the eye, not in front of it. The suspended square of glass lights up from both sides, so a person speaking to someone wearing Google Glasses can tell if the wearer has the device switched on.

Thrun’s deep investment in the project seems to come from a personal aversion to the madly proliferating gadgets that stand between people and the world around them. The inspiration is to “get technology out of your way” so people “spend less time on technology and more time on the real world,” he says.

And for someone who hopes to see us endowed with an all-seeing electronic third eye, Thrun is remarkably hostile to his devices. Cellphones are a distraction that make us socially “cut off” from an environment, he gripes. He’ll finish a two-hour meal without once glancing at his phone. To him, phone calls are a “super negative” experience because they interrupt what he’s doing.

“I once saw a family of five children and two parents in a Lake Tahoe restaurant, where every single person was just looking at their phone while they were having dinner together. That made me so sad because they have this brief of moment of time with their family and they should just enjoy each other,” Thrun recalls. “I can’t tell if Google Glass has succeeded, but it’s a really big emotional thing for me: having the technology that we love and connections that bring us to other people. Technology is synonymous for connection with other people.”

Maybe.

A cellphone can slip into a pocket and be temporarily out of sight. Google Glasses are at eye level and constantly in your face, or on someone else’s face. Making it easier to snap and share photos all but guarantees we’ll take more of them and share more of them, thus connecting ourselves more directly to the people who aren’t present. Surveillance—and documentation—will become more pervasive as well in a world full of Google Glasses.

Does Thrun worry that omnipresent Google Glasses will make us more likely to disconnect from people around us?

“All the time,” he says, explaining that he and other Google X engineers have been wearing the device as much as possible to see what dinner table conversation is like once the novelty of the gadget has worn off. “Maybe the outcome will be socially not that acceptable, we don’t know.”

So far, he’s felt “amazingly empowered” by the ability to take pictures, share pictures, and bring people into what he’s doing at that very moment. To Thrun, Google Glasses’ primary appeal is as a camera. He predicts we’ll share ten times as many photos as we do now and that the images we share will be “uglier”— more personal, more authentic, and more of the moment. These intimate images of what we’re seeing right this instant — a baby’s face, the steak we’re about to bite into — will allow a kind of elementary teleportation that lets us each bring everyone along for the ride.

Your mind can be closer than ever to mine.

If Google Glasses embody Thrun’s vision for a device that brings people together, the house he’s building near Palo Alto is a wish for a home that does the same.

The frame of the house tops a gold, grassy hill on a $5.9 million, nine-acre plot of land in Los Altos Hills. Seen from afar, it might be mistaken for a red flying saucer that has descended on Silicon Valley. Designed by Eli Attia, former chief of design for Philip Johnson, the building is a squat, single-story cylinder with exterior walls made entirely of floor-to-ceiling glass. A glass cone protrudes from the roof at the center of the circle and directly below it, a spiral staircase leads to a garage. Thrun says with a touch of pride that at 5,000 square feet, the three-bedroom home is a fraction the size of its neighboring mansions. There are also no corridors or load-bearing walls in the floor plan, and much of the eco-friendly home is given over to common areas.

“It’s really compact,” Thrun says. “The idea to make as compact as possible so family stays as close together as possible.”

During the tour, a neighbor stops by to ask if Thrun will join him at this year’s Bohemian Club retreat. Like Thrun, he’s a member of this elite society where men—and only men—with big checkbooks and big roles to play in life get together to schmooze, booze, sing and pee in the woods, according to accounts. Thrun says it isn’t likely. Later, he tells me he wouldn’t want to go on vacation without his wife and son. The Laws Of Motion

Even as Thrun seeks to get gadgets out of our way, his vision suggests an effort to make humans a bit more like computers: more rational and less inclined to give into foolish fears. Thrun sees a very real and important place for technology that advances clarity, eliminates obfuscation, and gives people all the help they need to solve problems on their own.

Thrun approaches problems armed with facts and cool hard logic, and seems troubled by people who do otherwise. He has an impressive number of statistics at his fingertips: the energy efficiency of planes versus trains, the fraction of materials shipped to a construction site that go to waste, the number of years required to fly to Mars and the percentage of Americans who don’t believe in evolution (a number irksomely large, in his view). He imagines a device more instantaneous, personalized and melded with our mind than a smartphone, one that would elevate conversations by allowing user to more easily research and surface facts during a discussion. No more messy speculation or faulty memories.

“We’ve stopped thinking. We’ve really stopped thinking,” he says. “We don’t look at problems logically, we look at them emotionally. We look at them through the guts. We look at them as if we’re doing a high school problem, like what is beautiful, what makes me recognized among my peers. We don’t go and think about things. We as a society don’t wish to engage in rational thought.”

Thrun blames the sorry state of our minds on an education system that raises students “like robots” and trains them to “follow rules.” Thrun’s pedagogy, at Carnegie Mellon, Stanford and now Udacity, leans heavily on learning by doing. He advises that I take up snowboarding so I can understand the laws of motion by living them rather than memorizing them in a classroom.Thrun also believes that connectivity is fundamental to learning. It’s through interactions with as many good minds as possible that good ideas take hold.

Conversations with people like Dean Kamen, Elon Musk and Google’s co-founders are crucial to Thrun’s problem solving process. He listens, debates and tests ideas out on people to see how they react. Being around Page and Brin makes Thrun feel “stupid,” like “a schoolboy,” and he says he can’t get enough of it.

“For me these are the high points of my life: When I go in and somebody just shows me how dumb I am and how little I know. That’s what I live for. Just to learn something new,” he says.

On a recent afternoon, Thrun is at Udacity’s headquarters in Palo Alto, just blocks from Stanford’s campus, rallying the troops. He has called an all-hands meeting and the company’s 30-odd employees, mostly 20-somethings in jeans, are gathered in a semi circle around him leaning on desks, squished onto couches, or sitting cross-legged on the floor. His two co-founders, David Stavens and Mike Sokolsky, former members of Stanford’s self-driving car team, have also joined.

“The purpose of this week has been for me to think about where the focus is and I know all of you have been asking me for this and it’s obviously something I’ve been slacking to do and not doing really well, so score me on the performance review and make sure that you put a check mark on ‘Sebastian is not particularly fast,’” he tells his staff.

Since Udacity launched in 2011, first under the name Know Labs, over 730,000 students have enrolled in classes—including the 160,000 that registered for Thrun’s first online course, Introduction to Artificial Intelligence—and 150,000 of them are actively taking Udacity courses. Enrollment is down, Thrun acknowledges, though he doesn’t say by how much.

But Thrun is undaunted.

“If we do a really good job here, then we’re going to shape society, together with our partners and other entities in the space, to really, really redefine education,” he says. “That’s pretty cool for a mission. That’s much better than being Instagram.”

Thrun predicts education will radically transform in the next ten years. Like blockbuster films, blockbuster online classes will command huge audiences and cost millions of dollars to produce. Many alma maters will shutter their doors as low-cost, high-quality online courses put second-tier schools out of business. Learning won’t stop the moment careers begin, and instead co-exist with work throughout life. He hopes to see teens start working earlier. Books will play a reduced role in teaching and short-but-comprehensive, quiz-intensive lessons will replace them.

Udacity marks Thrun’s effort to make all of the above come true. He’s after an audience of people from 18 to 80 years old, from Sacremento to Shanghai, from novice to knowledgeable. Thrun calls Udacity the “Twitter of education,” in keeping with his vision that universities “will go from mammoth degrees to 140-character education.”

Shorter, more digestible units created by professors concerned with teaching, not tenure, will seamlessly “fit” in students’ lives. Udacity’s lessons — YouTube videos split into segments three to five minutes in length — feature a professor narrating principles or equations as they are sketched out by a disembodied hand.

Each lesson ends with a quiz, followed by an explanation of how to properly answer the problem.

Unlike traditional universities, Udacity plans to turn a profit. For a fee, the company will provide official certification to students who pass course exams at an in-person testing center. Udacity also plans to play matchmaker between students and companies looking to hire them, and, like LinkedIn, will charge firms to browse its database of resumes. Upsetting the status quo in lecture halls around the country has become big business and Udacity faces a growing number of competitors, most of which have, unlike Udacity, partnered with existing universities to produce their courses. Coursera, a company that’s the brainchild of two Stanford professors, boasts a dozen partners from Princeton to Penn. EdX is a not-for-profit initiative founded by Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to provide instruction online. And 2tor is working with a growing roster of universities to offer online graduate degrees in business, law and nursing, among other fields.Thrun says he welcomes these rivals because more choice is the best thing that could happen to students.

Udacity looks to be a breeding ground for cultivating the talents of the young Thruns of the world: motivated individuals who want to learn, know what subjects they care about, seek a braniac community and are determined to teach themselves, no matter what. It’s the experience Thrun didn’t have growing up, but would have wanted. Classes are structured around solving a problem — building a search engine, programming a robotic car — rather than mastering theory or reviewing a canon. The thirteencourses offered so far cover programming physics, math, statistics and artificial intelligence.

“It’s opening up the chances for other people to also become innovators,” Zachary, the venture capitalist, says of Udacity and Thrun. “It is passing forward his spirit of innovation.”

Thrun considers Udacity his most important undertaking and it will perhaps prove his most challenging one. Regardless, he doesn’t think about his legacy and he doesn’t imagine he’ll be remembered in a generation. After all, he’s only human.

“I screw up every day,” he says. “I have a broken piece of glass in my car. I almost got a ticket this morning.” In the meantime, he plans to keep aiming high.

“Question every assumption and go towards the problem, like the way they flew to the moon,” he says. “We should have more moon shots and flights to the moon in areas of societal importance.”

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.