At the Rochester Institute of Technology, where I serve as President, we survey all graduates 90 days after graduation to find out how many of them have found employment or are attending graduate school. Such surveys are conducted by many colleges and universities, and they are used to evaluate career placement offices and student preparation for advanced study. Last fall, the results of this survey of RIT graduates was, as usual, very impressive. In fact, 95 percent of last year's graduates reported they were employed full-time in their chosen field of study, or were attending graduate school full-time. The response rate to the survey was also impressive at 78 percent.

Now some readers will say that these results are so good because RIT is an engineering school and engineers are highly in demand by employers, but, in fact, RIT is a comprehensive university with 18,000 students enrolled in more than 150 degree programs, including many in the liberal and fine arts. So why do such a high percentage of our graduates find jobs in their field? The answer is simple: Almost 80 percent of them get up to a year of experience in industry or government before graduation.

RIT is a co-operative education university, meaning that almost all of our students are required to spend a year out in the field gaining real-world experience before graduation. These internships, referred to here as co-ops, are almost always paid, and RIT sends more than 3,000 undergraduates each year to more than 1,900 employers in the U.S. and overseas. 70 percent of RIT undergraduates who participate in these internships receive a full-time job offer from their co-op employer, and this materially improves their employment rate upon graduation.

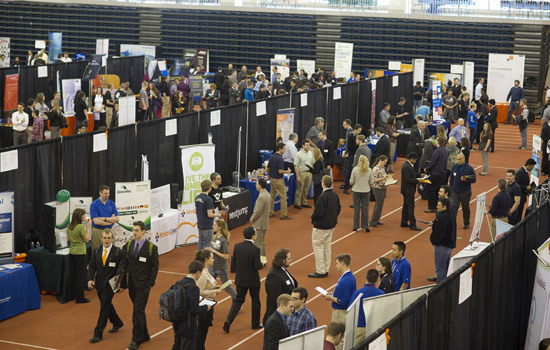

In addition, because RIT graduates already have real-world experience, employers line up to hire them upon graduation. In fact, we have had to restrict access to our fall and spring fairs by employers because we have run out of space to accommodate all that wish to come to recruit our students.

Another beneficial outcome of this requirement is that it forces currency on RIT faculty members. Professors who try to teach from 10-year-old notes find that students returning from their co-op assignments know how things are done in the real world right now, and they don't tolerate faculty who don't keep up with their profession.

This wonderful program also produces another, frequently misunderstood, result. Because the co-op requirement adds a year to the undergraduate degree programs of most of our students, RIT has one of the lowest four year graduation rates of any selective private college or university in the U.S., and for the same reason, our five and six year graduation rates are also lower than those of similar institutions without such a requirement.

Which brings me to my central point:

Many college ranking organizations, and even the proposed new federal rating system for higher education use graduation rates as a key indicator of student success. I think this is a fundamentally flawed notion. If we were to take this notion to the extreme, we would discount the value of community colleges, where graduation rates are low for various understandable reasons, or discount the value of institutions that take in marginal students and find a way to bring many of them to successful outcomes. We need a wide variety of higher education institutions to serve our needs for an educated citizenry, and to meet workforce needs, and to claim that one institution is better than another on the basis of graduation rates seems to me to imply the wrong definition of student success.

So I would suggest two things:

First, if we must use graduation rates as part of ranking schemes, let's adjust our definition of these rates and measure them against degree program duration requirements, not an artificially imposed four, five or six year standard.

Second, let's include employment rates and graduate study participation in our definition of successful student outcomes. And if we can find a way to include civic and community service, we should do that as well. These changes would incentivize colleges and universities to improve for the best of reasons -- the future success of their students.