My grandmother never used to phone me, so when I heard her voice on the phone that night in 1985, I was startled.

"I just read your book," she said sharply, "and I don't like it." She meant my first novel, Slow Dancing, which had recently been published by Knopf and greeted with far more attention than I had expected, "When are you going to write a book your grandmother will like?"

I knew what she meant: the book was filled with sex -- the pre-marital kind -- and references to it, beginning with the opening line. To her, it was "about" sex, but to me it was about two women best friends, finding their ways professionally and romantically in the plenty-of-sex pre-AIDS 1970s and '80s. They were women who cared about doing fulfilling work and having fulfilling sex, until men worthy of greater investments came along and made them rethink their blustery attitudes.

This is all pretty standard fare for the 21st century, but back in 1985, it had an edge, a boldness, that made people take notice. I was on to something: Sex! Careers! Friendship! I was famous for 12 or 15 minutes back then, but my success was no match for what happened 10 years later to Candace Bushnell.

When she wrote a book about these matters, Sex and the City, she had the good sense to add money, clothes and New York's obsession with status to the mix (my characters defended immigrants, and I doubt they thought for 10 seconds about their "wardrobes"), and earned quite a few more dollars than I did. I only dwell on this alternate Mondays.

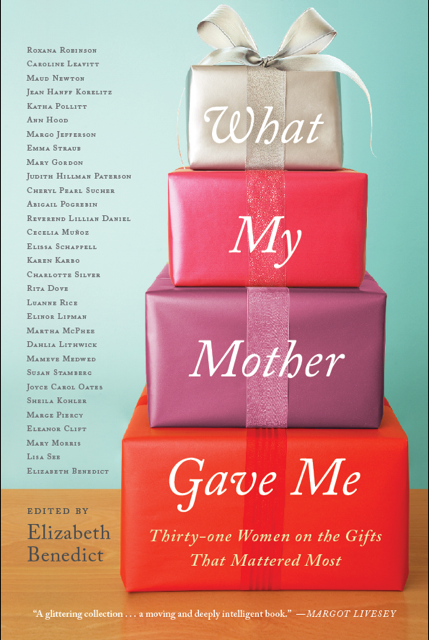

In the decades that have passed, I've published many books, and hundreds of articles and essays. But it's only in the last week that my grandmother's phone call has come back to me, as I talk in public about my new book, What My Mother Gave Me: Thirty-one Women on the Gifts That Mattered Most, an anthology I edited. I asked 30 well-known women, nearly all of them writers, to choose a favorite gift from their mothers -- most wrote about an object -- and use it as a lens through which to explore their relationships with their mothers.

Rita Dove wrote about a box of nail polish. Joyce Carol Oates remembered the quilts her mother made that comforted her when her husband died. Caroline Leavitt told the history of an important family photograph. Roxana Robinson told the story of her horse Babe. And I wrote about the scarf my mother gave me shortly before she died. Once she died, I became obsessed with it, though never spoke to anyone about it -- because I didn't have the words for the mixture of grief and confusion it created. Years later, still thinking about it, I wondered if other women had a gift from their mothers that meant as much to them. My book came from that question.

I could call this the first book that I know for certain my grandmother would like, if she were still alive. But more seriously, it's also the first book in which I've written candidly about my feelings for my mother, who died in 2004 after many years of dementia. She was a sweet, kindly woman of many gifts, especially for painting and sculpture, but had been beaten down by life, by a long, bad marriage to my father, and a bad divorce, which left her with nothing, and resulted in decades of worry. She worked, as a secretary, but did not have a cushion of any kind. Without Medicare and Social Security, and Medicaid, when she had to move to a nursing home, she would have had nothing.

I grew up precocious, as many kids do in Manhattan, and from an early age, I was independent and found a woman who lived in our building whom I decided I wanted for my mother. Unlike my mother, she was bold, glamorous and had a big personality. It certainly helped that she was from Los Angeles and had worked as a model. She didn't seem intimidated by any of her husbands -- and she seemed to travel through the world as though she were a movie star instead of a depressed, downtrodden mother.

Of course I loved my mother, and felt sorry for her, and wanted her life to be better, but I did not want to identify with her. I wanted to keep my distance. I wanted to be another sort of woman, another sort of wife. When it came to whether or not I'd become a mother, I spent many years trying, many years wondering if I wanted to. My husband and I eventually signed up with an adoption agency. But by the time they called with a child for us, I understood that my marriage was rocky and that I would have to leave it. I didn't want a child as much as many of my friends did, those who adopted in unhappy marriages, adopted solo, or gave birth with donor sperm. I didn't have an overwhelming need to connect with a child because I hadn't had all that great a connection with my mother.

All during these years, I was writing novels that delved deeply into the feelings of my characters. But the mothers in my novels had no relation to my own mother, except in a later one, where the main character's mother has a walk-on part as a mom losing her memory, which seemed generic enough to mask the more complicated truth.

My mother didn't appear in my fiction because I had no way to describe -- or do I mean to disguise? -- the distance I felt from her. When certain popular books or magazine articles about mothers came to my attention, I didn't read them. I no more identified with the community of women and their mothers than I identified with Queen Noor of Jordan -- an American woman about my age who had grown up in the U.S. and then married a Middle-Eastern king. Sure, we had come from the same place -- but we ended up on different planets.

When I looked around at my closest women friends, almost every one had a tragic mother story, one more heartbreaking than the next. I was comfortable with women who'd had damaged mothers, mothers who had never been quite all there for them.

During the years my mother lived in an assisted living facility and later a nursing home, where I visited her often, the distance between us wore away, slowly, and belatedly. After she died, I became attached to the scarf she had given me, bought in the assisted living facility, from a vendor who had come for the holidays. My attachment to the scarf, and to the way it came to symbolize my new closeness to my mother, led me to wonder if other women had such a gift from their mothers, a gift that encapsulated the relationship, that opened to the door to its history and complexity.

Dozens of well-known women writers knew what I was talking about, and contributed an essay to the new anthology. But I didn't write the essay I knew I wanted to contribute until I received all the others. I was too busy editing to take time out to write -- and, more important, I knew I had to back myself into a corner to write candidly, to delve as deeply into my real feelings as many fictional characters I'd created have delved into theirs.

I gave myself a weekend. I stayed in a bedroom alone with my computer and piles of all the other essays. I laid in a supply of food. And though I didn't drink any alcohol or take a mood-altering drug, I wrote in something of a drunken trance about the scarf, about my history with my mother, and how and where the two intersected. I was in my 50s, both my parents were gone, and there was nothing holding me back from telling the story. I'd asked 30 other women to tell their stories. It was only fair that I tell mine. And it was certainly time.

Rainer Maria Rilke tells us that everything serious is difficult, and that everything is serious. The reward for doing the difficult work is often that we feel lighter afterwards, and that we can revel in the accomplishment, the lightness, and the light for a good while, before we are compelled to move on.

Cross-posted with gratitude from Meg Waite Clayton's 1st Book Blog.

If you want to submit a photo of a favorite gift from your mother and the story behind it, please visit our tumblr page.

Elizabeth Benedict is the author of five novels, including the bestseller Almost, and the Joy of Writing Sex: A Guide for Fiction Writers. She is the editor of two anthologies, including the just-published What My Mother Gave Me: Thirty-one Women on the Gifts That Mattered Most (Algonquin original paperback).