"I think it's my most... skillful film," Stanley Kubrick stated in his calm, equanimous voice, the day after screening the first assembly of A Clockwork Orange.

We were standing on either side of Stanley's desk in his functionally chaotic home office at Abbots Mead in Elstree, England, going over the agenda for our imminent meeting with Dick Lederer, senior vice president of advertising-publicity at Warner Bros.

Stanley always spoke precisely, especially on matters of great importance, and he had to have contemplated all available adjectives before deciding on "skillful" to contextualize Clockwork within his body of work. It was a word I'd never heard him use before.

The highest echelon of Warner executives, headed by chairman Ted Ashley, had flown in from Burbank for the event, their first look at any frame of Kubrick's latest film. Overwhelmed at what they saw, they conveyed their enthusiasm in a euphoric meeting immediately following the screening.

After they left, Stanley kept Jan Harlan, his brother-in-law and executive producer, and myself, his head of marketing (though "marketing" was a word yet to be adapted into industry parlance) in the wood-paneled conference room at Pinewood Studios (where Clockwork had been screened) and grilled us for two and a half hours, extracting our response and opinion about every scene and detail in the film. It was both exhausting and exhilarating -- an unscheduled and unexpected display of his trust in our honesty... and loyalty.

I had offered Kubrick my uncensored opinion of one of his films on a previous occasion, in 1968, when I was an executive at MGM charged with spearheading an alternative marketing campaign for 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film's premiere was panned by critics, so under enormous corporate pressure -- and having not seen 2001 with an audience prior to its opening -- Stanley cut 19 minutes from its length in five days. I told him then, with certainty, that "for those who got 2001, the 19 minutes were a bonus; for those who didn't, the cuts wouldn't matter." (The 19 minutes were recently "rediscovered" in a Midwest storage vault). The cuts didn't affect the critical response.

But this was different. I was being formally interrogated about a film that was still unfinished. Stanley, however, insisted on immediate feedback, and my hesitation evaporated -- for we never hedged. With Stanley, hedging was a waste of valuable time.

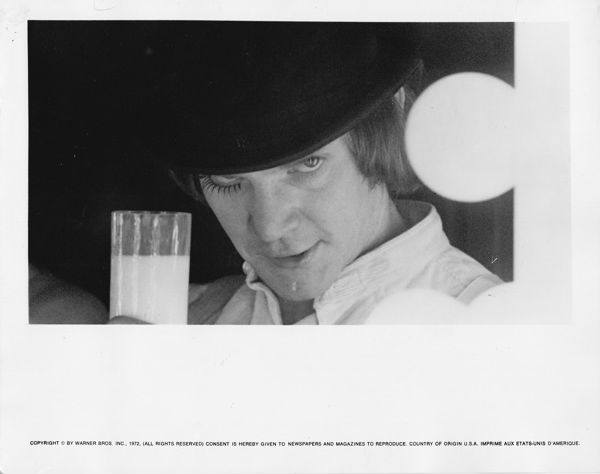

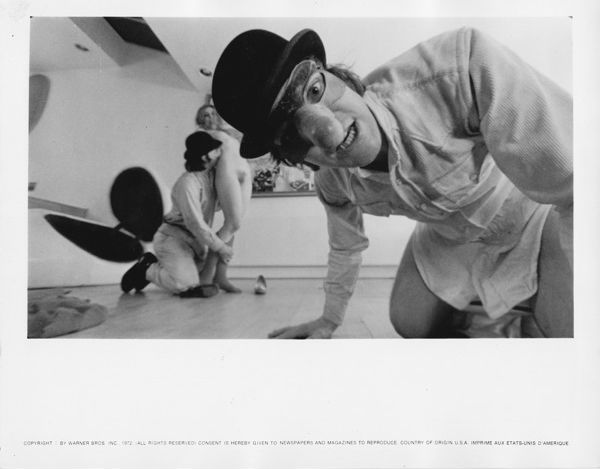

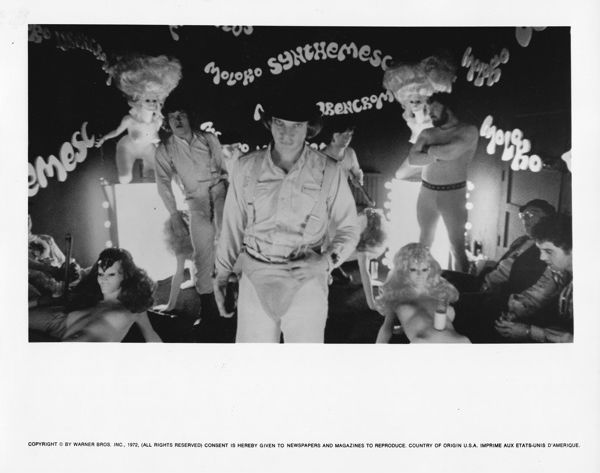

For two months after my arrival in England, in May 1971, I had been carrying on an unusual relationship with the footage that would come to constitute A Clockwork Orange. Between our daily pattern of lunch and evening work sessions, Stanley wanted me to choose the stills that would be necessary for publicity. Movie promotional images were always produced by unit or special photographers on the set who photographed what they saw. Stanley held, correctly, that these traditional film stills weren't an accurate representation of what was on screen and he prevailed with the studio in the unprecedented process of taking the images directly from the film. (Stanley, who had begun his career as a photographer for Look magazine, always had strong opinions about the medium.)

Later, these frame stills served another purpose in the screenplay edition of Clockwork, as Stanley used them to depict every editing cut.

So each day, for three to five hours, I would sit in front of a Moviola -- the hand-fed editing machine through which all the printed film passed -- watching every scene from every angle as assistant editor Gary Shepherd loaded the takes, removing the frames I marked with a chalk pencil and placing them in slide holders to be culled later. The work was complicated and time-consuming. Later, the color frames had to be converted to Stanley's high standards for black-and-white stills, for newspaper reproduction.

But though I had seen every take of the film, I was largely in the dark, for Stanley insisted I watch without sound, responding purely to the visuals.

The only time I violated his directive was after a week of hearing a buoyant Malcolm McDowell singing slices of "Singin' in the Rain" from the editing room below my office. It finally became too frustrating -- I had to know how the song was used (it wasn't in the script, which I wasn't allowed to read anyway) and forced the editors to show me the sequence with picture and sound. The scene -- McDowell's prancing rape of Adrienne Corri before an apoplectic Patrick Magee -- was startling in its daring and ingenious in its conception. It confirmed everything I knew from Kubrick's prior movies and from the Anthony Burgess novel upon which the film was adapted - A Clockwork Orange would be another Kubrick revelation.

Settling into the rhythm of Stanley's questioning, Jan and I responded quickly -- which wasn't easy, as the film had twisted our emotions, seducing us into sympathizing with McDowell's uniquely amoral yet dangerously appealing protagonist. Halfway through the conversation, we came to his seduction of "two young devotchicks" in a sped-up ménage a trois timed to the William Tell Overture. The sequence was sexy, funny and inventive -- and the coupling was repeated twice.

I said that it was dazzling but that repeating the bedwork felt like milking the audience, though I didn't know what effect he wanted. Stanley held that the second threesome would still get laughs.

The scene remained intact until six months after the film's X-rated U.S. release, when he removed 11 seconds to secure an "R" rating. Three seconds from the second shagging were eliminated.