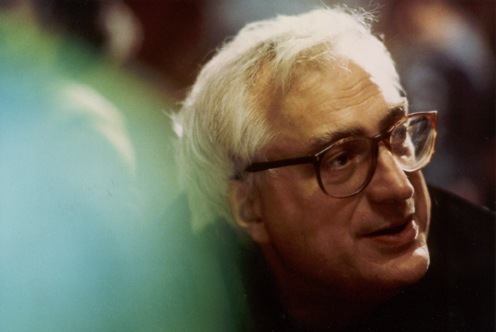

It was a delight to chat with the legendary director, Bertrand Tavernier. Nominated for two BAFTAs, 14 Cesar Awards (taking home four), and winner of the Best Director award at Cannes (for "A Sunday in the Country"), the 72-year-old filmmaker has helmed some of the best films to come out of France over his 40+ years in the business, including "Clean Slate," "'Round Midnight," "Life and Nothing But," "A Sunday In The Country," and "Safe Conduct."

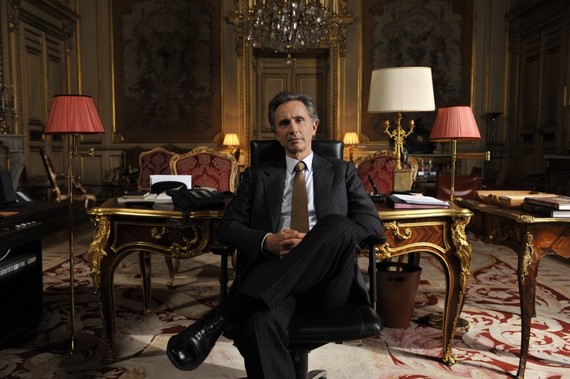

His new film, a political farce called "The French Minister," starring Thierry Lhermitte, is one of his only pure comedies.

We sat down to talk about it, and other related topics.

John Farr (J): I admire many of your films, yet few I would classify as comedies. Had you done any comedy before this?

Bertrand Tavernier (B): "Revenge Of the Musketeers" was definitely a comedy period film, a tongue in cheek swashbuckler. "Clean Slate" was very dark, but it was a comedy. And in many of my films you have long moments of comedy. Even in "Safe Conduct" you have about 20 minutes of comedy with one character going to England with a document nobody understands; and nobody understands his story, and he's coughing, and he wants to go back to France. I think it's a kind of epic journey but done in a rather funny way. So I did comedy moments inside of dramatic films. But it's true that here, I was confronted with a real comedy from the beginning.

J: How did you view your primary challenge with this film?

B: The challenge was to be both funny and true, even in the farce. I wanted the feeling that maybe some of the things are a little bit exaggerated, but basically they are true. Sometimes we cheated a little, but you can feel that it's not invented. That the minister character (based on former Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin) was crazy and hysterical and emphatic, but also had great culture and a great vision. But he was totally chaotic in his way of expressing it.

He never changed his vision. He always thought that we must avoid war in the Middle East. That those weapons of mass destruction did not exist, that they were lies developed by the neocons. He kept repeating that we should all go through the United Nations, but expressing that in different speeches, he would change his mind, contradict himself, ask incredible things of his people, not read what they've been writing. I mean, his behavior was absolutely impossible.

J: Did M. de Villepin see the film?

B: Oh, yes. And he found the film was very true. He talked to the screenwriter and praised many things in my film. He said that this episode was exactly as we portrayed it. I think maybe he thought his treatment was actually a bit too restrained.

J: I like this man!

B: Still, he has a tremendous ego. But his ego is not concerned by self-appreciation. He likes to be seen as somebody completely unique, completely bizarre. Not the typical politician - very well groomed. He likes to be portrayed as somebody who yells and screams and changes his mind, yet has a tremendous knowledge of books. He can be emphatic and completely mad sometimes. But he loves being seen as somebody outrageous.

First, he was the foreign minister. And he was very good. In our film, the minister gives a speech at the end; that was de Villepin's real speech. Minister of Foreign Affairs was a good job for him because it demands a certain amount of vision and knowledge of the French language and culture. And he had a kind of Gaullist attitude, which was impossible for his collaborators, but at the end it created a good result. He stopped a civil war in Africa; he was in agreement with Chirac on that. They decided France would not go with the US to war in Iraq, which at the time was very strongly attacked in this country, in a very unfair way, because we were right. And he knew - and all the people working for him knew- that there were no weapons. The French Secret Service knew it perfectly. Not to say the guy leading Iraq was not a tyrant - he was - but he had nothing to do with 9/11.

But after that, Dominique was not a good Prime Minister. Because as Prime Minister, you have to devote yourself not to a wide vision, but to concrete little things. Like how much teachers have to be paid, what's the relationship with the union, what does the government have to do with the workers - things that bored him.

You can see in the film, very clearly in the way that I shot it and the way Thierry Lhermitte plays it, that reality doesn't interest him. He believes in his vision; he never notices that papers are flying around whenever he comes in, which will be a pain in the ass for the secretary who'll have to collect them; he never looks. He cannot understand that the people who work with him need a rest. He will call in the middle of the night. There is nothing like a holiday, or a Sunday. You have to work with him all the time. Reality has no existence. And I think Thierry Lhermitte shows that beautifully.

J: Thierry, whom I remember as the victimizer from "The Dinner Game," one of the funniest comedies I've ever seen, was terrific.

B: He was wonderful; he has the charm, the elegance. When he quotes the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, you believe that he has read him, which is not the case with every actor. He told me, "I will have to play this totally sincerely. I must sincerely think that "Tintin" (a famous French comic book character) is a good way of describing the situation in the Middle East." And when I was shooting that scene, at one point he came to me and said, "The more we do the scene, the more I believe the Minister is right." I said, "You're perfect. You're perfect."

It's something I told all the actors in my film: You're not doing a comedy. You are not funny. You do not think that you are funny. A lot of comedies, at least in France, are done by people who do stand-up comedy. And so, sometimes, it's a series of punch-lines, a series of jokes where people know they're making a joke. This is the opposite. This is something where people were acting very, very seriously. The fact that they're acting seriously in such a crazy, chaotic background, working under contradictory orders - that's the humor. The irony was coming out of that clash between the work and the conditions under which the work happened.

J: I loved Niels Arestrup, too, as the seasoned Deputy who keeps calm and a measure of control. I've seen him in a lot of things.

B: He's a superb actor, but most of the time, before this film, he was playing dangerous guys. Yelling. He told me when I met him: "Bertrand, you are asking me to do the opposite of what I've done for 40 years. And it will be very difficult for me because I love to play unrestrained characters. I love to externalize... I'm not introverted, and this is my nature." And then when he won the Cesar for Best Supporting Actor, he said that I had the courage to think he could be funny, that it took a lot of courage, and that it proved I've always been a director who refuses to typecast actors. In fact, I like getting from actors the opposite of what other people ask them to do. Niels gave me a wonderful and warm tribute.

J: Because he hadn't done a lot of comedies, I don't think.

B: No! He has done mostly dramas, many films where he was really frightening, playing devilish, nasty, violent characters!

J: So here's a question for you based on this film. You must know that Americans are very cynical about politics and government in this country. Approval ratings are at an all-time low. Is it the same in France?

B: It is the same in France. I think it is deserved. They deserve it because they are not confronting the real issues. They are always thinking that to solve a problem, you just need to mention it on television. They are betraying the promise of creating forty or fifty thousand new jobs for teachers. I wonder, why did they have to give exact figures? They could have said, we want to have a real examination of the situation in every school, which will take a few months, to see if certain schools require new teachers, while others do not. Examine the situation and decide.

The problem is now a lot of politicians are behaving like the French in the First World War. They gave orders, but they never knew the reality of the trenches, they never went there. They were living outside the suffering of the people. To give you an example, at the end of 1914, when the French started to take the first German trenches, they discovered the Germans had built shelters out of cement. The French made them out of wood and mud, which was cold, wet and caused illness. So they discovered that.

It took one whole year for the French government to absorb that news, and ask by the middle of 1916, that they should build a different kind of trench...meanwhile the troops were getting dysentery.

So you cannot ask a politician to know and do everything, but he has to be surrounded by people who do know the reality. Not the reality of the bank system, the reality of the people who are oppressed by the bank system.

J: The actor you're most linked with is the late Phillipe Noiret. What was special about him, as a man and an actor?

B: As a man he was a gentleman. During my career, he was faithful with me. During the 18 months I was trying to get "The Clockmaker" produced - and everyone was turning me down- Philip stood by me. When we were doing the film, I said, "Philip, I would have understood after eight or nine months, if you said, 'Okay, we tried. I can't go with you anymore.'... Why? Why did you stay with me?" He looked at me, very surprised, and said: "I'd given my word."

J: Wow. That would be rare in Hollywood, I can tell you.

B: Yes. So, I said, we will work together. And later he said very beautiful things in his book of memoirs. He said, "Without Bertrand, I wouldn't be the actor I am, and I wouldn't have had a great career." So that was very, very nice.

In his work, he was extremely funny. Great to work with, inspiring, never wanted to over-psychoanalyze the character, but work through the problems, the detail of the costumes, doing a lot of formal work. He was always ready to add something new. He was carrying the other actors. It was wonderful to have him on the set. I loved him.

J: And he was a real friend?

B: He was a friend. We were constantly seeing each other, constantly talking to each other. He was somebody who... he was a brother. He was a brother, a father, somebody belonging to my family.

J: I loved his work too. Know what I just saw, which you can't get over here, and I love finding things that you can't get over here- was his "Very Happy Alexander."

B: Ah, it's very funny. Very, very funny. A lovely film. But the favorite part of his for me was "Life and Nothing But."

J: Yes, which I love, and it's on our site. Great, great film. So what was your favorite Noiret collaboration?

B: Well, I would say "Clean Slate" and "Life and Nothing But" are two of the best films we did together. But I enjoyed most of them. "Joy Reigns Supreme" was wonderful. I enjoyed them all. I enjoyed so much working with him. He had a sense of humor. He had one other great quality: You could put him in any period, any kind of role, he was believable in them all. He could be a Prince of Blood in the 18th century, the bourgeois in the 19th century, the common man of the 20th century, you were believing him. You were believing him as a clockmaker, an engineer, a lawyer, or a laborer. He could own a café. He made you believe he had done that job for 20 years. Also he could travel in time; he was totally at ease in the 18th century, where some great American actors might look disguised or out-of-place.

J: Speaking of American actors, I know you're a fan of classic American cinema. What are some of the American movies from the Golden Age that you love the most?

B: There are so many. Raoul Walsh, John Ford, Ernst Lubitsch. Even some unsung director like Andre de Toth. In France, I have a connection; I insist on getting a lot of Westerns released in France on DVD which are impossible to find in this country. Like "The Wonderful Country" by Robert Parrish, which is one of my favorite films. I have so many comedies - Gregory La Cava's "My Man Godfrey". Screwballs, I love screwballs. "His Girl Friday," of course. But I love also British and French cinema. I love cinema!

J: To watch, and to make.

B: To watch, but when I'm actually making a film, I'm not a film buff anymore. I'm totally devoted to the film I'm making. I don't watch other films. I've been asked, "Have you seen 'His Girl Friday,' or 'One Two Three' again?" and I say no. I know them, I know the pace of "His Girl Friday," but I don't want to see these films again. I want to concentrate on the characters I'm dealing with, I want to understand, I want to learn. All of the films I made happened because I wanted to learn something.

For instance, with "In The Electric Mist," the French version is totally different from the American version, which is the producer's. My version, you can find in France. I wanted to learn about Southern Louisiana. And the greatest compliment I heard was from John Goodman and Tommy Lee Jones at the Berlin Film Festival, who both said that it was the one of the truest films about Louisiana. It was the same kind of compliment I had from Dizzy Gillespie, who said that ""Round Midnight" captured the essence of Jazz.

J: That's a big compliment.

B: Yeah! That one from Dizzy, that was great. For a French director, it's not too bad.

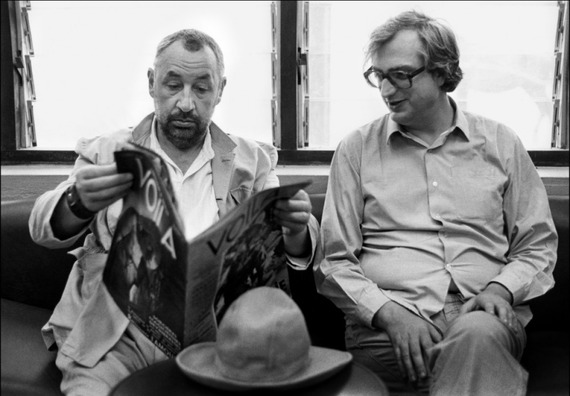

J: Last question. The first person you ever worked with was Jean-Pierre Melville. You know what I just saw? "Le Silence de la Mer." Loved that.

B: It's a very impressive film. His first- he produced, financed, did it all by himself. A very daring film.

J: And nobody's seen it over here.

B: A very daring film. But he was very difficult to work with. I mean in a way you could see. Because for me, "The French Minister" could be an allegory about filmmaking. Because you have directors who behave in a crazy, terrible way. I mean Jean-Pierre was really frightening. I mean I suffered. I was a young player in the field, and he made me suffer. Suffer! He was humiliating people, he was yelling. That was horrible. And yet he helped me also. But I mean, the result? The films are terrific.

J: What did you learn from him, if anything?

B: I learned to be demanding. To never be satisfied. I also learned not to be like him on the set. To be the opposite. Never humiliate someone publicly. Never. I'm not going to make it my job to humiliate other people, which he was doing. Apart from that, yeah, he was demanding.

With not a lot of money, he could create that special shot. I learned how to do a lot with very little, compared to a lot of Americans here who need a lot of money and equipment. He did not need that. He had a small staircase, and with just that he created an incredible shot. That he was great at.

Also, he was a superb storyteller. When he wanted to shock you, you could not sleep until he was taking you in his bed and telling you stories. I mean, I was under a spell. That was wonderful to see him like that, to listen to him. And he had that degree of love for filmmaking. He was going to work on the editing in the middle of the night. So for the girl working in the editing room, it was a nightmare, because it was exhausting.

J: He was like the French Minister.

B: He was! He was. Because he was obsessed by his vision. And strangely enough, he didn't realize that what he was doing was sometimes the opposite of the people he was trying to emulate. For instance, he was obsessed with William Wyler. On one shot he was trying to film, he really wanted to do it like Wyler. But he could not resist having the shot last 40 seconds longer than Wyler would have. And suddenly, it becomes more like Bresson than Wyler. That was Melville. But he was brilliant.