Few directors are as willing to venture into the abyss as Werner Herzog. His prolific body of work has ranged from intense dramas like Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Woyzeck that plumb the depths of the human soul to documentaries like Encounters at the End of the World and Grizzly Man that examine humanity's fragile place in the miraculous and terrifying world of nature. The astonishing breadth of Herzog's filmmaking conveys the humanist's sense of wonder at the world - what he describes as the "ecstasy of observation."

Herzog's latest film, Into the Abyss: A Tale of Death, A Tale of Life (opening this Friday, November 11th) is a compelling look at the contentious issue of the death penalty. Producer Erik Nelson has stated that the film is intended to inform the current Republican presidential debate over the death penalty, in particular with regard to the candidacy of Texas Governor Rick Perry. Herzog himself has issued a Director's Statement expressing his opposition to capital punishment - though in keeping with his lifelong aversion to political interpretations of his work, he has also asserted that Into the Abyss is not a political film. These apparent contradictions point to the enigma of Werner Herzog himself - on the one hand a sensitive humanist with strong moral convictions, yet on the other hand an artist who resists being defined by political activism or party ideology.

Into the Abyss embodies these contradictions. The film tells the true story of a brutal triple murder committed in Conroe, Texas. Michael Perry and Jason Burkett, intending to steal two cars owned by Sandra Stotler, killed Stotler in her home and then lured her son Adam and his friend Jeremy Richardson into the woods and executed them. Perry and Burkett subsequently went on a joy ride in the cars, before winding up in a bloody shoot-out with the police. Perry and Burkett were convicted of the murders, with Perry receiving the death penalty, and Burkett receiving a life sentence.

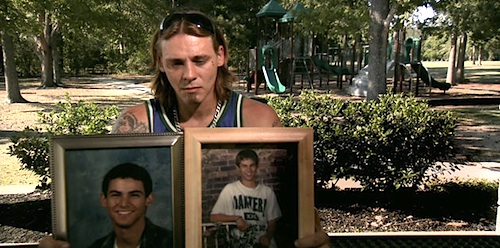

Herzog interviewed Michael Perry just eight days before his execution, and also interviewed Jason Burkett in prison. Other interviews include those with Burkett's wife Melyssa Thompson-Burkett, who contacted Burkett while he was in prison and subsequently married him; Fred Allen, a prison captain who worked in the execution chamber and who assisted in over 125 executions before resigning in moral crisis; and most significantly, the relatives of the victims themselves: Lisa Stotler-Balloun, the daughter of Sandra Stotler and sister of Adam Stotler, and Charles Richardson, the brother of Jeremy Richardson. Stotler-Balloun and Richardson in particular provide the most heartbreaking testimony of the film, as Herzog does not shy away from depicting the shattering effect of the murders on their lives. As a result, Into the Abyss exists in a complex tension between Herzog's avowed position against capital punishment and his impulse as a storyteller to depict both sides of the story and allow readers to make up their own minds.

I had the opportunity to meet with Werner Herzog in Los Angeles recently and discuss with him Into the Abyss and his extraordinary body of work. Part I of this interview appears below.

GM: I'd like to ask you about the title of your movie, Into the Abyss, because I've seen you refer to the concept of 'the abyss' quite a few times in your work. In Woyzeck you have a line "Every man is an abyss, you get dizzy looking in," and in Nosferatu you have a line "Time is an abyss profound as a thousand nights." This is a concept you keep referring to - what does 'the abyss' mean to you?

WH: It's a good observation, and when I came up with the title Into the Abyss - it dawned on me that it could have been the title of quite a few other films. Like Woyzeck could have had that title, or The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner or even the cave film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, because I've always tried to look deep inside of what we are - deep into the recesses of our existence, of our prehistory - like in Cave of Forgotten Dreams. So it is some sort of a theme that runs through quite a few of my films.

GM: I want to ask you about the relationship between humanity and the universe. There was a wonderful quote at the end of Encounters at the End of the World where Dr. Gorham asks, and I paraphrase, "are we the means through which the universe becomes conscious of itself?" This reminded me of a quote from Blaise Pascal's Pensées:

"A reed only is man, the frailest in the world, but a reed that thinks. Unnecessary that the universe arm itself to destroy him: a breath of air, a drop of water are enough to kill him. Yet, if the All should crush him, man would still be nobler than that which destroys him: for he knows that he dies, and he knows that the universe is stronger than he; but the universe knows nothing of it." (Trans. A.J. Krailsheimer)

This seems to apply to Into the Abyss and its depiction of human beings within this world. In the film you go driving down country roads and you show the trailer parks, the run-down stores, the boarded up gas stations, the bars. It looks like a wasteland that God is somehow absent from, and there are these people in the midst of it who are in a terrible state of pain and confusion - in an apparently indifferent universe.

WH: Let me address Pascal first. Yes, I like him very much. I even invented a quote for the film Lessons of Darkness. It starts with a Pascal quote "The collapse of the universe will occur like the creation in grandiose splendor," and underneath it says Blaise Pascal, but I invented it - and of course Pascal couldn't have said it better. [Laughs.]

But, it's interesting. The wasteland, this forlorn landscape, has become fascinating for me - this lost kind of Americana. And one of the death row inmates with whom I spoke - not in this film but in another film I'm already finishing - he said to me how he saw on his very last trip forty-three miles between death row and the death house where they are being executed in Huntsville. And in this cage in the van he sees a little bit of an abandoned gas station, he sees a cow in the field, and all of a sudden for him, everything is magnificent, and he says: "It looked like Israel to me, it all looked like the Holy Land." And I immediately grabbed my camera and I did this voyage of the forty-three miles and indeed the most forlorn landscapes all of a sudden look like the Holy Land. So I look at these forlorn landscapes all of a sudden with fresh and different eyes.

GM: I was also very struck by the similarities in the comments of three of the people whom you interviewed. Lisa Stotler-Balloun spoke about the four years of terrible loneliness she suffered after the murders of her mother and brother, when her life was empty, when she lived withdrawn from the world and felt her life had no meaning. Then there was Michael Perry himself who, despite the fact that he had killed three people and was on death row, said that the circumstances he was in had no impact on him. He had literally blocked the prison walls out. And then there is Fred Allen, the former prison captain who worked in the execution chamber, who talked about quitting his job and finally discovering his real self. These are all different formulations of the same feeling of dissociation from the world through tragic circumstances - of being split from the world, cut off from reality, cut off from one's own true self. This seems to be a recurring theme in modern filmmaking and literature.

WH: Yes, but ... we shouldn't speak about Perry who was executed eight days later. It was some sort of a mechanism to keep his sanity - to talk himself into being innocent, although he had confessed twice, and in detail, and there is overwhelming evidence against him. So there's no real doubt about his guilt. But the film is not in the business of guilt or innocence.

But let's talk about Lisa Stotler-Balloun and Fred Allen, the former captain of the tie-down team. Both of them in a way are not disassociated anymore from the world, from friends and society. They have somehow managed to move back into it. Lisa Stotler has somehow overcome the worst of her nightmares. Fred Allen is a tormented soul, but somehow he's back. He gave up his profession at the cost of losing his pension and today he has a company that does logistics - supplies for the trucking business. And he all of a sudden discovered for himself a very meaningful life where he sits back and watches nature and enjoys the birds. The film actually ends with the wonderful, wonderful text where he says he keeps watching the birds, and what are the ducks doing, and all the hummingbirds - pause - why are there so many of them? Cut. End of the film. What a fantastic question.

GM: It's a very poetic ending. It reminds me of that shot of Klaus Kinski playing with the butterfly at the end of My Best Fiend, in terms of the individual having that connection with nature and life. So there's hope after all for reintegration with the world.

Melyssa Thompson-Burkett was to me the final figure who was very striking - that she was drawn to this convicted killer. What is it in women that is drawn to that darkness in the death row inmates?

WH: You should answer it [chuckles], you are a woman.

GM: An urge to danger, an urge to nihilism, a desire to tame evil?

WH: I do not know. It's very mysterious. There's always a mystery between men and women, and thank God it exists. [Chuckles.] What kind of life would it be without this mysterious attraction that men and women have for each other, and love? It comes out of the blue, it comes out of nowhere. Melyssa meets the inmate for the first time and falls in love and she witnesses a rainbow from the gates of the prison - to her, she knows he's innocent. And they belong together. So, in a way it's very moving, but more mysterious than anything else.

GM: It's in that mysterious space that all the good art and all the good filmmaking happens, where you have a chance to go into the world of the imagination, to go beyond the world of the intellect.

WH: Yes. That's always been a quest of mine.

In Part II of this interview, I discuss with Werner Herzog his Rogue Film School (currently accepting applications), as well as his attitudes toward Avatar, pantheism, yoga, New Age nutritional supplements, Wrestlemania, and the end of civilization.