When my daughter Lotus recently became interested in astronomy, and we began watching shows and documentaries about space and the universe, we discovered Neil deGrasse Tyson, the dynamic host of the National Geographic talk show "StarTalk." While Neil is a world renowned and brilliant astrophysicist and author, and director of the prestigious Hayden Planetarium, he is also an immensely likable, jolly, and warm personality - one who exudes joie de vivre, as well as a contagious, passionate energy for expanding frontiers of science, human thought and innovation. Which is perhaps why, during my interview with him at his office at The Museum of Natural History, wearing his trademark tie of planets, he took such personal interest in my very outdated, essentially obsolete yet beloved RCA microcassette recorder, picking it up as if it were a fossil from prehistoric times asking incredulously, "What is this?!" When I explained that I used it as a back-up, a relic from my days 20 years ago as a magazine reporter, he couldn't control himself. He proceeded to take over my iPhone, setting the interview up to record on the Voice Memo application, beginning the recording with his trademark booming radio announcer voice: "And now, I am Neil deGrasse Tyson for HuffPo interview..." before handing my iPhone back to me, all ready to go.

That anecdote is a sampling of his humor and how he sees his role, as a teacher and provocateur, educating people in entertaining ways about what they should know -- about the universe, about science, and about ourselves and the world around us. He has done this through a variety of mediums: as the host of StarTalk, the popular podcast and National Geographic Channel talk show, as well as the miniseries Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, as the author of 10 books, including the best-selling Death by Black Hole: And Other Cosmic Quandaries, as well as cultivating a social media following with his thought-provoking and informative tweets. He is also the recipient of the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the highest award given by NASA to a nongovernment citizen.

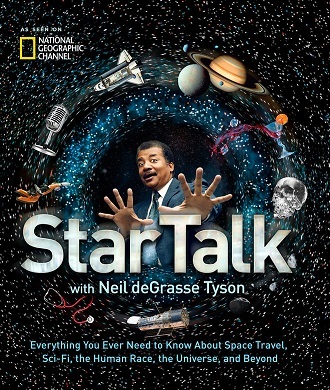

StarTalk, his two-time Emmy-nominated late-night talk show, is an outgrowth of his popular radio and podcast series of the same name and seeks to bridge the world of pop culture and science through intimate interviews and lively discussions with an eclectic roster of guests hewn from pop culture, politics or news discussing how science and technology have affected their lives and careers. The third season of StarTalk will premiere on Monday, September 19th, with actress and comedian Whoopi Goldberg, followed by a diverse lineup of other high profile guests this season including astronaut Buzz Aldrin, actress and neuroscientist Mayim Bialik, U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, comedian Jay Leno, Olympic Gold Medalist Hope Solo, actor Ben Stiller and more. Natgeo Books has also just released an illustrated companion book to the series, STARTALK: Everything You Ever Need to Know About Space Travel, Sci-Fi, the Human Race, the Universe, and Beyond which curates the best of "StarTalk" and dives deeper into some of the most intriguing discussions from the show.

In our conversation below, Tyson talks about his passion for helping people discover "what role science plays in their lives," why he thinks education should teach our students "how to think," what gives him awe and the essential impact of seeing ourselves and the world through a "cosmic perspective." When you do, Tyson states emphatically, "it changes everything."

Marianne Schnall: First of all, I wanted to let you know that not only is my 15-year- old daughter a fan, but so is my 18-year-old daughter, my husband, and my father, so you are officially multigenerational, which is a good thing. What is it you most want to accomplish through StarTalk and why did you decide, rather than this just being a science show, to bridge science with pop culture?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's a perfect question, because -- when we think of science, we think of this subject that's taught in a classroom, and you're either good at it or you're not, or you're interested in it, or you're not. And you can just walk by it and say, "Oh, I don't like science but I like history," and you go learn history, as though science is this compartmentalized topic that you can climb over, walk around, dig under, or ignore. And it occurred to me that, "No, of course, science is not that. Science is everywhere." And it especially touches pop culture. So if we create a radio show that pivots on a pop culture foundation, then we can -- think of it as a scaffold. It's a pop culture scaffold that walks into every episode of StarTalk, and we then clad it with science that fits that pop culture topic. I don't need to train you on that scaffold -- pop culture by definition means everybody knows what it is! I have a guest, and you know who that guest is because that person is a famous politician, or singer, performer, artist, whatever. And so I already have you half way. It's the rest of the way that is the celebration of science on the program. So I think it's just a more honest account of what role science plays in our lives. The popularity of StarTalk, I think, is evidence of how well that resonates with people.

MS: And the fact that it has cross-generational appeal is also a really good sign.

NDT: By the way, part of that might be the multiple platforms that it's on. Because I have an identity that exists apart and separate from StarTalk -- like I'm active on Twitter. That leans young. So people say, "Oh, I like Tyson's tweets... oh, he also has his radio show or TV show." And so there are tributaries to the show that do come from different demographics coming together, so I am pleased to learn in your case of the multiple generations.

One other thing: the honing of how we do StarTalk, some of it comes from these other places. So I'll send out a tweet that's pure science, and there'll be some interest in it. But if I connect the science to something pop culture, the interest is ten times greater. So these are insights that I glean daily by people's reactions to how I juxtapose information. So I use that to inform how we do shows with StarTalk.

MS: I feel like we often forget that we actually are on a planet spinning through space. I guess my question is: why do we seem to forget that we are one family on a planet spinning through space, and if we retained that perspective, how would that change the way that we treat the environment, each other and other forms of life on this earth?

NDT: It changes everything. You're absolutely right. And it's a cosmic perspective. The embarrassing part of this is that I and every one of my colleagues carry this perspective with us all the time. And what's embarrassing about that is we sometimes take that for granted, and we have to say, "Oh, my gosh, these other people I'm in this cocktail party with do not live with this awareness. So let me put in a little extra effort to alert you of this, of what's going on in the universe, to put our existence in a context that will either have you re-balance what you think may be important in your life or rethink how you're allocating your energies in the service of yourself versus the environment versus the planet as a whole." That's what a cosmic perspective does.

So yes, it's extremely important. Let me tell you how important it is. I can assert without hesitation that the modern environmental movement where we're caring for earth was born while we were landing on the moon, 1968, '69, and '70. 1968 was our first mission to the moon, Apollo 8. People don't think about it much, because they didn't land. They just went, and orbited and came back. Apollo 9, 10, and 11 would take us into 1969. You go to the moon, and what happened? We looked back, took a picture of earth, and discovered earth for the first time. There it was adrift in space, the dark void of space. And we saw it not as -- it's hard to even go back and remember this or think that it could have ever been this way -- but we saw earth not as earth appeared in social studies class with color coded countries, no. We saw earth as only space can reveal it to you. And there were oceans, land and clouds.

So like I said, we go to the moon, and we discover earth for the first time. After that photo was published, Earthrise and then the Blue Marble -- in that interval of time, we changed as a culture. They say what is it worth to go into space? We changed as a culture. By the way, we had plenty of other priorities on our plate -- there were assassinations, and a cold war, and a hot war, and a civil rights movement, and campus unrest. Yet, we found the time to create the Environmental Protection Agency! That was 1970. Oh, my God. Why didn't we create it in 1960? No one was thinking about it! 1950? Nobody was thinking about it. 1980 could be too late! Environmental Protection Agency under a Republican president, I might add.

What else happened? No one had thought of the atmosphere of earth as part of earth much before that. Ask someone to draw earth before 1968. They'll just draw earth and the continents - no clouds, no atmosphere. So this juxtaposition of ocean, land, and atmosphere became administratively codified in the founding of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA was founded in 1970. Comprehensive Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Protection of Species Act -- some of these existed in sort of skeletal forms earlier. They came of age in the versions that were ratified in 1970. What else happened in 1970? The first Earth Day. Why didn't we have an Earth Day in 1965? 1967? No, 1970. And then 1972, leaded gas would be banned. Catalytic converter would be introduced. So this is my long way to answer your question with a yes. Knowing space matters -- maybe more because it recalibrates what it is to know ourselves.

MS: Why isn't astronomy a required part of a standard educational curriculum so we have that foundational awareness? Why do you think that is?

NDT: Well, the curriculum is ossified for generations, and there's a lot of baggage. Is that the right word? There's a lot of legacy educational habits that exist particularly in the American system. I don't know the other systems very well.

MS: So without our school system, how can we change things?

NDT: No, I would change [the school systems] - I mean I'm not there yet, but I plan to work on that as one of my projects: What can we do with the future of the school systems? Is the portfolio of topics the right ones? Should you get an entire class on a cosmic perspective? What kind of math should you be taught if at all? There are people who say they don't need their math. I think that's a mistake, because it implies that what you learn is what you then apply. Whereas, in the best scenario what you learn -- the act of having learned it -- has established a new form of wiring in your brain that empowers you to have thoughts you've never had before. And by studying math, and by struggling to do a math problem set, and with every new problem you solve, it's a new wiring of your brain. And if you only think of school as, "I want to learn this so that I could apply it here," you'll be ill equipped to navigate the rapidly changing frontier of what actually matters in society. What is it now -- the average time someone spends in a job is three years or five years before you move? Whereas the generation before us, they would spend 30 years working in the factory or working for their company. So you're a freshman in college saying, "What should I major in to have the best chance of having a good job?" Well, major in "how to think," and then you can apply that to any job that arises that at this moment is unforeseen, because you're not getting out for another four years and if you go to graduate school, it's another seven or eight.

MS: You have this new companion book to the series, which is great - there's so much that's in it...

NDT: Can I say something? I didn't know in my heart how this would turn out, because it's organizationally ambitious. And I'd see the PDFs when they'd come about, but then when the book arrived in my box two days ago, I said, "Oh, my gosh, this is fun." And I'd say that even if I had nothing to do with the project. I mean I'm pleased to hear that you like it, because it's -- any page you turn, "I want to know about that! Oh, my gosh, this is cool too!" And it is the soul of StarTalk.

MS: I went to a local observatory recently, and I was shocked to see details so far off in space I had never seen before in the night sky. For example, stars that are different colors and shapes, twin stars that look like one but are actually two, and one of the furthest stars in the sky that was actually a cluster of a million stars. I was just awe-struck by the vastness of what is out there. What gives you the most awe? How would you describe the beauty of the universe?

NDT: So, philosophers historically like speaking of truth and beauty going together. And I don't think of beauty, because that value judges what you're looking at. Is the sunset beautiful but the underbelly of a tarantula not? Yet they're both part of nature. Is a squirrel cute but a rat ugly when they're both rodents? One just happens to have a furry tail, and the other doesn't. So to say something is beautiful is value judging nature, and I refuse to do that. I refuse to value judge what is beautiful and what is not. I accept it all as being part of nature.

And is a virus bad because it's trying to survive and it happens to give you a fatal disease? It's just being its own thing. We have the power now to render certain strains of mosquitoes extinct by disrupting their reproductive cycle. Should we? Well, the mosquitoes are bad for us. Bats eat them -- so I'm not going to say, "We're in charge. We don't like the mosquitoes. Fine. Get rid of them." I'm not going to say they're being bad mosquitoes. It's just we're making a decision, sort of a rational decision for our own survival as any creature would do in the interest of its own survival. The lion actually doesn't care if zebras go extinct. It's not thinking that. It just wants to eat the zebra. Okay. Now, if zebras do go extinct, then they'll eat the gazelles. They don't care, right? So for me, my awe comes not so much from the universe, but from our ignorance of the universe. If you add dark matter and dark energy together, which are two unknowns in our modern science -- we know they're out there, we measure their existence, but we don't know what causes it, we don't know what it's made of. If you add them together it's 95, 96 percent of all that drives the universe. I'm in awe of that. I'm in awe of how much we understand and have used to shape our civilization and to think of how much we have yet to understand and what that could mean for the future of civilization.

For more about StarTalk, visit www.channel.nationalgeographic.com/startalk/

Marianne Schnall is a widely published writer and interviewer whose writings and interviews have appeared in a variety of media outlets including O, The Oprah Magazine, Marie Claire, CNN.com, AOL Build, the Women's Media Center and The Huffington Post. She is also the co-founder and executive director of the women's website and non-profit organization Feminist.com, as well as the co-founder of the environmental site EcoMall.com. She is the author of Daring to Be Ourselves: Influential Women Share Insights on Courage, Happiness and Finding Your Own Voice and What Will it Take to Make a Woman President? Conversations About Women, Leadership, and Power. You can visit her website at www.marianneschnall.com.