Afghanistan has always been a patriarchal society. Some Afghan women still need a male relative's permission to pursue an education, to work, or to travel. It is often male relatives who choose when and to whom a girl marries. A father or a brother can decree that a girl is no longer permitted to attend school. A husband can require his wife to stay at home. And the country has long struggled with an embedded culture of violence against women.

"We Are Afghan Women: Voices of Hope" is a book about women, but men play an important role in their individual lives, and in the best of cases overwhelmingly for good. Many of the women who speak in the pages have fathers who have encouraged their education or husbands who have supported them in their business or professional pursuits. Parliamentarian Naheed Farid would not be in Afghanistan's Parliament without the steadfast support of her husband and her father-in-law. As Zainularab Miri, the beekeeper of Ghazni, says of her father in the opening story, "He and my mother gave me all the same chances that my brothers had." Other women tell how their education or their success has helped to change attitudes of the men in their families. Many, though, say that their father or their husband or their brother is "not like other Afghan men."

Nang Attal is one example. He has devoted his life to girls' education. The sole male voice in "We Are Afghan Women," Nang tells of his own brave efforts to work on behalf of Afghan girls and young women. We are honored to share part of his story.

Nang grew up in the Khawat Valley, about 60 miles from Kabul, in a tribal region. Both of his parents were illiterate.

"Under the Taliban there was no girls' education and also earlier during the mujahedeen time, there was no girls' education in the countryside. After I started going to high school, my mom asked me to teach the girls in our valley how to read and write. I had about five girls sitting in my mother's mud-brick kitchen to start and from there that number grew. My mom would teach them to say the religious prayers and after I would teach them the basics of reading and writing.

"At first, I was writing on the wall with a piece of charred firewood. But that wasn't very effective. So we had to find a blackboard. That was a struggle. But once you find a blackboard in the countryside in a third-world country, then you have to find chalk. There was no chalk anywhere, so sometimes I would just steal some chalk from my boys' school and use it for the girls' school. All of this happened around 2002, right after the Taliban left power.

"Gradually, the number of girls in our home school grew. I was going to school in the morning and in the afternoon teaching at my mom's school. Some of the girls I taught are now midwives, they went on and got more intensive education."

Nang went on to graduate from Kabul Education University and was awarded a prestigious Fulbright scholarship to study in the United States. He has been a visiting researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and earned a master's at Golden Gate University. In 2014, he received a United Nations Youth Courage Award for his work on behalf of Afghan girls and young women.

"So now for Afghanistan and for the younger generation we first need to recognize and to admit that we have problems. And then we need to address those problems. And I think in my sense all this begins with educating our sisters. If we educate our sisters, they will educate our future children. If we educate our sisters, we can better and equally use our natural resources. We are a rich country in terms of resources--how can we not use 50 percent of our talent to become a wealthy country?

"There are three reasons why I became so committed to education, and especially girls' education. The first one is my mom. Even though she was uneducated, even though she had suffered a lot during the Soviet invasion and the mujahedeen civil war, she wanted us to learn. Every morning when we were leaving for school, she knew in her heart that we may not return back. But she still let us go, she was determined and sold eggs and did handicrafts to support our education. She did not spare any effort. So how can I give back to my mom? I can't teach her; she's somewhat old now to learn. The best way is for me now to give back to my sisters. If my mom can stand up for our education, why cannot we as brothers stand up for our sisters' education and support that?

"The second reason is that when I used to teach in the village, the girls there were so talented. They were very smart. The sound of teaching in that kitchen is still echoing in my ears. I would give them some homework, and say, okay you just need to read the next chapter. The next afternoon, they would come back and they had not just read that chapter, but the next chapter as well. They were asking

more questions than I would be able to answer. They would do all their homework, and they would also do all the women's work and housework, like take the cows out to feed them or bring water. And they would still read a chapter ahead.

"The third reason is my dad. My dad would always say no guns. He fought back against the Soviets, but with us, he would always say you don't need to take up guns at any time. Never any guns, never. He had seen how bad it is.

"A determined struggle always has the chance of victory.

"You cannot change the village overnight. It took about 15, 16 years for my family and dad to change. And it will take even longer for more families in rural areas to change. I grew up there. If you take a hard approach, if you pressure the society to send their girls to school, that is not going to work. But I think the power of storytelling can.

"I have seen pictures of girls in my valley studying computers. For me to see girls in our valley sitting in front of computers is equal to women walking on Mars. Maybe that is what one of these girls will do at some point. I carry that hope in my heart, mind, and soul."

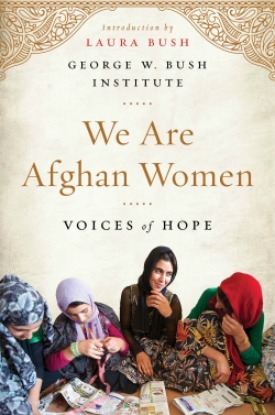

Read more of Nang's story and 28 other inspiring stories of resiliency in the book, "We Are Afghan Women: Voices of Hope."