In October 2013, a small group of Central American migrants arrived at a shelter in Mexico's southern state of Oaxaca. The journey from Guatemala was difficult and perilous. The migrants navigated a maze of local violence, police harassment, and a variety of natural hazards on their way north. The freight train's arrival in Ixtepec, Oaxaca signaled short relief.

But the journalists awaiting them were unsatisfied.

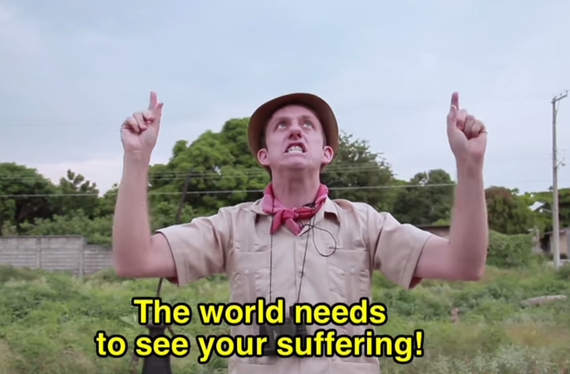

You're not expressive enough! they complained to the arriving migrants. Give me more drama!

This is the nasty face of the White Savior Journalist. Part of the broader White Savior Industrial Complex, these reporters make their pilgrimage south, offering international exposure. But the results of their charity coverage are mixed, if not downright destructive. In many cases, the journalist saves only himself and his do-good portfolio.

The plight of migrants is fertile ground for the White Savior Journalist. According to Martha Pskowski, who volunteered at the Oaxacan shelter back in 2013, "Media would arrive for their 24 hours, waiting to see if the train was coming around. They would get their shot and take off."

Journalists yell, make demands, push and pull at the migrants like a theater director blocking a scene. And in the end, "it is the same old story of those poor migrants and the terrible things they go through," Pskowski says. "There is no agency at all."

In other cases, the consequences of the White Savior Journalist were more severe. Pskowski told me one story in which a film crew encouraged a group of migrants to board a freight train so that they could catch footage of their journey. It was a proposed win-win: journalists get their footage; migrants get the protection afforded by press credentials and northern passports.

But the journalists only stayed for a few hours. With their footage, they hopped off the train, leaving the migrants vulnerable to the very dangers they sought to alleviate: violence at the hands of gangs, capture by local police, or deportation by an increasing iron-fisted immigration authority.

With these horror stories in hand, Pskowski teamed up with filmmaker Gregory Berger to make Danger: Journalists Crossing. The short film pokes fun at the wrongheaded journalists exploiting these migrants and provides an instruction manual on how to do this work responsibly -- undoing the White Savior Complex in the process.

The film was made in collaboration with Central American migrants in both Ixtepec, Oaxaca and Mexico City. Instead of being props in a sob story, these migrants -- from Honduras, El Salvadora and Guatemala -- are the protagonists.

The lesson is simple: Listen, learn and empower. According to Armando Medina, a Central American migrant featured in the film, journalists are all too quick to tell stories of the powerless migrant victim. But letting migrants tell their own stories -- of struggle yes, but also of triumph, solidarity, and grassroots organization -- is key. "Everyone knows that the world is sad," says Medina. "But the story of a creative, organized and effective struggle is more powerful than a thousand stories of sadness and tragedy."

The rebuttal is valid. Journalists are responsible for communicating the facts, not skewing in support of local causes. More important, stories of migrant hardships have -- in many cases -- served to increase public awareness and public sympathies for the migrant cause. If you can squeeze a white protagonist in there, as Nicholas Kristof has argued, you can probably squeeze even more tears out of readers and even more dollars out of their pockets.

But sometimes the efforts of the White Saviors backfire. Last summer, as thousands of Central American children arrived at U.S. borders, coverage of their struggles multiplied. Many expected that the response of the American government -- and the American people -- would be a humanitarian one.

Instead, the response was largely "law and order". Children were detained, many without due process. And even though new federal funds were directed toward support of the migrants, the increased attention sparked fresh protests against immigration and fresh calls by congressmen for the hardening of the border with Mexico.

The tale of last year's immigrant crisis illustrates the unique perils of reporting on migration. So much of America's anti-immigration movement relies on a foul depiction of the migrant -- helpless at best, criminal at worst. When reporters fail to depict the humanity of migrants, they do more than defame the migrants -- they inform the policies that prevent migration at large.

Indeed, the war of words against migrants is endless and varied. In Mexico, immigration authorities claim they are "helping" when they detain migrants, "saving" when they deport them.

Or worse: In March, a Mexican federal deputy announced that "migrants are a danger to Mexican citizens" because "wherever they arrive, they bring prostitution, poverty and assault the Mexican people." The voices of the migrants are missing completely.

This is the call that Medina makes in Danger: Journalists Crossing -- to give the portraits of migration back to the migrants themselves.

In order to undo the work of the White Savior Journalist, we must start here. Migrants have their own stories to tell, and their aim is not to solicit pity. It is to showcase the concrete ways in which migrants can organize to claim their rights and address the systemic problems that force them to leave their home countries. As Medina claims in the film, "if we convince more migrants that there is power in organization, there is nothing we can't do."

On a smaller scale, giving voice to migrants is itself a form of empowerment. According to Paola Quiñonez, another actor in the film, telling stories allows migrants to reclaim their identities -- against the anti-immigration crusade. By speaking out at a recent press conference, Quiñonez became more than a victim. "The media called me Paola Quiñonez, defender of migrant women," she said in a recent interview.

Avoiding the pitfalls of the White Savior Journalist can be difficult. Living in Mexico, I struggle constantly to be effective, respectful and supportive of local causes as a young white man from the North. Needless to say, I am still working through this challenge, day by day.

But the message of Danger: Journalists Crossing is a hopeful one. There are simple strategies for journalists to stop acting as saviors. We can't just drop in, extract our story, and depart. We must take the time to listen, develop relationships, dedicate resources, and ultimately, allow the migrants themselves to steer the ship.