In the beginning, there existed an island -- uninhabited but for the Arctic fox -- sculpted by snow and ice, wind, water, and fire. This wild, windswept land had no name, until settlers arrived in the 10th century, and made this place their home. The unnamed island eventually became known as Ísland (Iceland). Early citizens took up an artistic pursuit that is still revered today, some thousand years after the first boats washed ashore. They became writers, crafting stories based on the early settlers, stories of villains and heroes (and monsters), of battles and disputes over land and power, love and money. These tales are Iceland's natural treasure -- known as the Sagas.

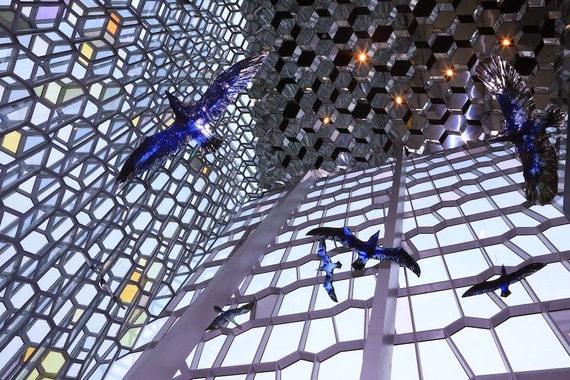

Iceland's identity is intimately wrapped up with this literary tradition. Wander through the exhibits at the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik and you'll learn that, up through the early 20th century, the country had few other artists except for writers. Sjón, a celebrated Icelandic poet and novelist, told me that for centuries, this poor country produced neither paintings nor symphonies, but they had one constant cultural activity: writing. Iceland's only Nobel Laureate, the beloved and prolific Halldór Kiljan Laxness, was awarded the prize in Literature in 1955. (His home is a much-visited museum.) In 2011, Reykjavik became the first non-English-speaking city to receive UNESCO recognition as a City of Literature, one of only 11 cities receiving this designation.

I strolled the snug waterfront capital, spotting facades bearing UNESCO City of Literature plaques with scannable QR codes. Each indicates the role the venue had in a piece of literature or its connection with an author. A red painted corrugated house with a baby blue door along Ingólfsstræti is where Torfhildur Thorsteinsdóttir Hólm, the first Icelander to publish a historical novel, lived. In the middle of the block near the main tourist office stands a former soda bar-turned market that's the central setting of Vögguvísa or Lullaby, a Reykjavik-based novel depicting the life of the city's teens written by Elias Mar.

The Icelandic people take exceptional pride in their writing tradition. Sjón told me that when Iceland's economy hit rock bottom in early October 2008, that didn't dissuade the citizens from celebrating the birthday centenary of renowned poet Steinn Steinarr. Seeing this literary priority, an editorial in the conservative Icelandic newspaper, Morgunbladid, declared sarcastically that Iceland's core values may be focused more on poetry and culture rather than money. According to Björn, Chairman of the Executive Board of Reykjavik's City Council, "We have the most number of writers per capita than any other city in the world. I think every Icelander wants to be a writer." This phenomenon can be chalked up to a multitude of factors, including Iceland's long dark winters, the harsh weather, the sense of isolation, the dramatic landscape, and, of course, the Sagas, which Sjón refers to as "our Mona Lisa."

While their prized tales provide a wealth of inspiration about struggle and conflict, Iceland's drama also extends to its landscape: craters belch magma and ash, pools of mud boil and bubble, sulfurous geysers spew from cracks in the earth, and abundant geothermal energy is tapped for everything from residential hot showers to hot tubs at Reykjavik's man-made beach. With such an intimate connection with the earth's fiery core, this vibrant country and its buzzing creative capital, Reykjavik -- one of the most picturesque capital cities in the world -- can't help but inspire writers.

No wonder Canadian-born Eliza Reid, co-founder of the Iceland Writers Retreat with Erica Jacobs Green, and a journalist who has lived in Reykjavik for 12 years, considered their choice of Reykjavik for a venue as a no-brainer. "It's very respectable to be a writer here," said Reid. "Unlike many parts of the world where telling someone you're a writer often brings an incredulous response such as 'Do you make a living doing that?' in Iceland they'll want to know exactly what you're working on."

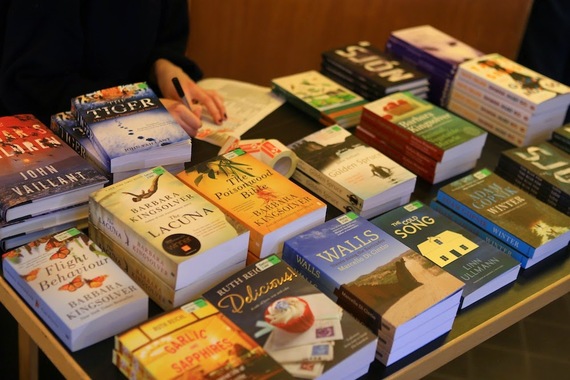

Writers retreats have blossomed all over the world. But, like everything about Iceland, this retreat -- in its second year -- is unique: no applying for entry, or arriving with manuscript in hand hoping to secure an agent. This is the writer's retreat for the people - one that's unpretentious and open to all, from the well-published author to the writer who simply keeps a diary or scribbles poems on napkins in coffee shops and then stuffs them into a file at home. The instructors -- a diverse array of notables in terms of age, country and genre -- are abundantly accessible and available, whether at the coffee breaks between workshops or the numerous excursions and receptions all over the city and beyond.

This year, 85 participants (including myself) and volunteers plus nine featured authors -- each taught two different 90-minute workshops -- ventured to Reykjavik for adventures aplenty, whether in writing or beyond. Some participants came from as far away as Australia -- over a dozen countries were represented -- with a couple from Myanmar and Singapore choosing to celebrate their honeymoon here, lured by the retreat's informality and approachability, the caliber of the authors and, of course, Iceland's spectacular beauty. This was displayed to dramatic effect when, after departing Thingvellir National Park, a scenic land of shifting tectonic plates and the site of Iceland's first parliament, one of the retreat's excursion buses threaded carefully through a whiteout only to come upon several cars stuck in thick snow drifts. Participants volunteered to join in the effort to push them free - and in the end everyone declared this delay a fitting episode in a great day in the land of fire and ice.

Another excursion was decidedly more mellow, but no less interesting. On a chilly walking tour sponsored by the Reykjavik UNESCO City of Literature, two guides alternated reading from Icelandic ghost stories, crime novels and, of course, the Sagas. We heard a ghostly tale that took place near the former morgue, where we stood on Grettisgata. This street was named for Grettir, the hero of the eponymous Saga in which he battles a violent ghost -- Icelandic ghosts, like so much in Iceland, tend to be quite dramatic. Later, in front of the old, but still functioning, prison on a street not lacking for law offices, we listened to an excerpt from Someone to Watch Over Me, by Yrsa Sigurdartdottir, a popular crime novelist. (Clearly, Sweden doesn't have a monopoly on the Nordic noir genre.)

The illustrious cadre of authors at the retreat were unusually forthcoming about their process. Sjón, who won the Nordic Council Literature Prize (the equivalent to the Man Booker Prize) for The Blue Fox, epitomized this sentiment in his workshop "Anatomy of a Fox." He declared, "I will open up my toolbox," breaking down the step-by-step process of how this small lyrical book was born. Like a collage, stories and books he'd come across served as his inspiration. A 19th century newspaper article about a monster that supposedly came ashore, autobiographies of fox hunters, a photo of a man bedecked in a white suit and bow tie standing incongruously in front of a turf house -- all were fodder for this slim, evocative tome.

In his workshop "Getting the Goods," journalist and non-fiction author John Vaillant chronicled how, in order to write The Golden Spruce, his book describing the destruction of a tree revered by the Haida Indians of the Pacific Northwest, he had to enter into and explore a world that was both unfamiliar and extremely inaccessible. Researching the cultural importance of this towering, unique Sitka spruce might seem simple enough, but he learned quickly that the traditional stories are considered property, owned by different clans, requiring permission to not just hear but also retell. Like Sjón, Vaillant also uses a collage approach, bringing together research from myriad disciplines (psychology, botany, sociology, mythology) to assemble his work. But when it comes to gaining access to the indigenous Haida and the other "foreign" worlds that he explores, Valliant advocates having a guide. In the end all the research pays off, according to Vaillant, because the better informed he was, the more "luck" he had with sources. "Make your mistakes with the people you can afford to lose, ask your stupid questions about taboo subjects with them; not the person who is closest to your story."

Taiye Selasi, a prominent British-born writer and photographer, brought her vibrancy, warmth and insight to both workshops I attended. In "Final Draft," we read a bit of "Little Miss Sunshine," learning how a screenplay can help sharpen our prose. "With just a handful of details: seven-year-old Olive wears glasses, is slightly plump, has frizzy hair, is big for her age and is watching a beauty pageant on TV, we know everything about this character," Selasi noted. For three minutes, she had us write a snapshot about a character of our choosing. This turned out to be one of Selasi's invaluable "get yourself unstuck" methods, as I call them. "Telling your reader only what they can see constrains you to action, emotion and circumstance; look at conveying circumstance through action and emotion."

Her second workshop, "Hearing Voices," was not about psychosis but, rather, how the first, second and third person (singular and plural) each convey a different perspective; a different sense of intimacy or authority. In one exercise, we wrote bits of autobiographical information on slips of paper that Selasi shuffled, redistributed, and then had each of us read in a different narrative point of view (my name is; your name is; his or her name is; our name is). What happens when we hear ourselves referred to in the third person? It feels distant. The second person? A bit accusatory. And the first person singular? Very personal. In another quick but revealing writing assignment, we described a scene using the first person plural, "we". I chose to recount my experiences accidentally eating the traditional and much maligned (by tourists) Icelandic snack: ammonia-tainted fermented shark meat. Reading this paragraph aloud evoked a sense of inclusiveness, as if all of us had endured the odiferous, sinus-exploding tidbit. Selasi suggested using this "we" voice to get unstuck: "Play with changing the voice. You can unlock something for your creative muscle."

Canadian novelist and poet Alison Pick offered us another method to break inertia in her workshop, "Character Development." Most of the session was devoted to a single exercise. Each of us chose one of our characters and, in groups of three, one member interviewed another who spoke in the first person as their character. The third participant acted as the observer, taking notes of the interaction, and then the roles were rotated. In my group, we each got a better idea about how to develop character motivation. "If I'm stuck with character motivation, I may do a first person from the POV of that character as a journal entry," said Pick.

Even the quiet moments I spent outside of the retreat were full of creative surprises. All I had to do was cross the street from the hotel and walk 15 minutes along a pedestrian path bordering a forest to the Nauthólsvík geothermal beach. There I sat inside a glass-enclosed cafe, gazing at the tumultuous sea while nibbling on a fresh cream-filled pastry and sipping a frothy cappuccino. For a writer, it doesn't get much better than this.