There are many reasons for an opera company to plan a new production. The most important factor for the creative team, however, is the chance to articulate a new artistic vision of a composer's work. Whereas landmark productions of beloved operas are often referred to by the name of their stage director (Jonathan Miller's Rigoletto, Frank Corsaro's Traviata, Francesca Zambello's Ring cycle), productions of The Magic Flute are more often associated with the artists who have designed them.

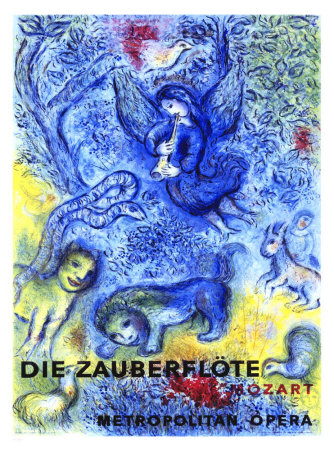

Two new productions of The Magic Flute debuted at Lincoln Center during the 1966-1967 season. In October 1966, the New York City Opera presented Beni Montresor's beautiful fairy-tale version. In February 1967, the Metropolitan Opera unveiled a new production of Mozart's opera designed by Marc Chagall.

Poster art for Marc Chagall's production of The Magic Flute

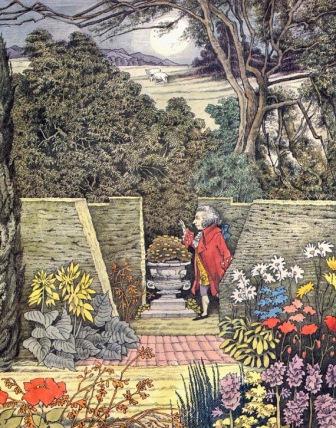

A scenic drop designed by Marc Chagall for The Magic Flute

* * * * * * * * * *

Chagall is not the only internationally famous artist who has created sets and costumes for The Magic Flute. David Hockney's famous production of Mozart's opera premiered at the 1978 Glyndebourne Festival Opera (click here to see a gallery of his set and costume designs). The following video clip of James Levine conducting the opera's overture includes a montage of Hockney's sets.

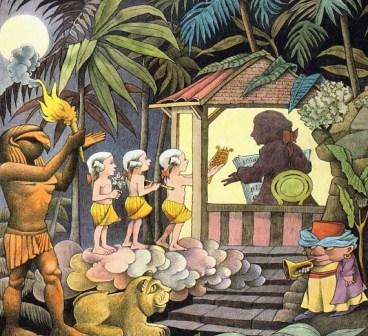

In 1981, David Gockley unveiled a new production designed by Maurice Sendak for the Houston Grand Opera.

Poster art for The Magic Flute by Maurice Sendak

A drawing by Maurice Sendak forThe Magic Flute

* * * * * * * * * *

Because The Magic Flute places heavy demands for props and costumes on a designer, there is always a challenge to create something new and delightful for audiences. The following clip from a 2007 San Francisco Opera production shows some of Gerald Scarfe's witty designs.

One of the most elaborate productions in recent years was designed by Julie Taymor for the Metropolitan Opera in October 2004. When Opera Australia staged Taymor's production in 2012, the production had to be scaled down to fit into a theater (the Sydney Opera House) that is less than half the size of the Metropolitan Opera House. As a result, many of the props were recreated "down under."

* * * * * * * * * *

In June, the San Francisco Opera unveiled a new production of The Magic Flute designed by Japanese-American artist Jun Kaneko (click here to view a slideshow of Kaneko's set and costume designs). To get a better appreciation of Kaneko's art, watch the following video clip:

Computers have played a major part in bringing Kaneko's artistic vision for The Magic Flute to the stage. As part of an intense design process (which included animating much of the artist's work so it could be digitally timed to match the pace of the production), Kaneko built a scale model of the stage of the War Memorial Opera House to use in his Omaha workspace.

Jun Kaneko's scale model of the stage of San Francisco's War Memorial Opera House in his Omaha warehouse

As Rory Macdonald began conducting the familiar overture, I was seized by a moment of panic as I watched Kaneko's computerized designs proceed to fill a giant scrim. "Is this entire production going to look like three hours of trying to choose a screensaver?" I wondered.

Happily, Kaneko's designs have a cumulative effect which seduces audiences with their easy mood changes and fascinating imagery. They also prove to be extremely flexible in key dramatic moments (such as when Tamino and Pamina must undergo the trials of water and fire in Act II).

Directed by Harry Silverstein with grace and humor (I love the two-headed dragon that reappears for a curtain call), the San Francisco Opera's new production was blessed with Albina Shagimuratova's fearsome Queen of the Night -- one of the best I've heard in decades. Adding to the fun was David Gockley's ribald new translation (a welcome relief from Andrew Porter's familiar script), which brought Papageno (Nathan Gunn), Monostatos (Greg Fedderly), Pamina (Heidi Stober), and Tamino (Norman Reinhardt) firmly into the realm of today's vernacular. At the performance I attended, the audience laughed easily, heartily, and frequently.

One of Jun Kaneko's designs for The Magic Flute

Occasionally, props will be moved on and off stage by a team of black-clad stagehands (as is common in the Japanese tradition of Noh theater). Western opera-goers who are used to seeing ancient Egyptian elements in an opera that refers to Isis and Osiris will, no doubt, be surprised to see Sarastro looking like he forgot to change his costume after appearing in the title role of Gilbert & Sullivan's operetta, The Mikado.

Over the years, I've attended performances of The Magic Flute that were sung entirely in German, performed entirely in English, or presented with a cast that sang all of Mozart's music in German and spoke all of the opera's dialogue in English. Gockley (who has now helped bring to fruition two artistic visions of Mozart's opera -- each designed by a major artist) notes:

When Emanuel Schikaneder offered Mozart a commission to compose a singspiel for a suburban Viennese theatre, he was compelled to accept. Singspiel is best compared with our own musical comedy -- songs separated by spoken dialogue -- all performed in German, the vernacular of the Austrian public. The idea was to create a popular form of music theater in a language the audience could understand. Often there were comic lines -- some improvised on the spot -- that could only come across vividly in the native tongue of the public. Regional accents added color to the text and characters.

Tamino is surrounded by Jun Kaneko's animals in The Magic Flute (Photo by: Cory Weaver)

The practice of Supertitles, which began in 1984, certainly got opera texts across to our public in a consistently successful way. Simultaneously, they gave the company an 'out' of not having to come up with great translations and drill casts to get English text successfully understood in a huge opera house. Supertitles solidified the practice of using 'the original language' as the lingua franca of the international opera company. The practice was welcomed by top-class singers who have increasingly refused to perform their roles in translations.

Pamina and Tamino undergo the trial of fire in Jun Kaneko's production of The Magic Flute

When we performed Magic Flute in 2007, I felt that something was missing hearing the work done in German. I resolved our next Magic Flute would be once again done in English (yes, with titles) and that I would personally be involved in the translation. Fortunately, our mostly youthful -- and mostly American -- cast embraced this concept, as did the conductor, Rory Macdonald. I want to especially thank our Sarastro (Icelandic bass Kristinn Sigmundsson) and Queen of the Night (the stunning Russian soprano Albina Shagimuratova) for making the effort to learn a version of Magic Flute they may never do again. Somewhere, Mozart and Schikaneder will be smiling.

Tamino encounters a two-headed dragon inThe Magic Flute (Photo by: Cory Weaver)

Because so much of the production's design is built on computerized projections of Kaneko's art, the animation in this version of The Magic Flute (which is shared with the Washington National Opera, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Opera Omaha, and Opera Carolina) adds an element of acceleration to the proceedings. As the eye adjusts to the constant motion of the art being projected on the flat (and occasionally angled) panels, it plays a neat visual trick on one's perception of performance time.

Whereas most productions of this opera rely on painted flats for scenery, Kaneko created more than 3,000 storyboard images to accommodate the work's 28-scene changes. As the artist explains:

Striking a balance between the musical and visual experience and the flow between the two from beginning to end is crucial. It's very tricky. Many times, the costume and set designer have different concepts and that can show easily (by doing both, I think I avoided a conceptual design gap). Lighting was a challenge, and I knew this would be a headache for the lighting designer. The front projectors in the piece can be particularly challenging because the singers cast shadows. The director, Harry Silverstein, felt that shadows are part of the piece and suggested that we not try to fight it. That really freed me up from a design perspective and we've come up with some interesting solutions.

One of the most impressive aspects of Kaneko's artistic vision is not just what it does for current audiences, but the potential it has to charm audiences of the future. The large pieces of necessary projection equipment can be found in any major city. The show's computer cues are easily transportable in electronic media. I anticipate this production will travel far and wide and enjoy a very long shelf life. Here's the trailer:

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape