When my friend and colleague Rev. Hal Taussig told me about his plans for "a new New Testament," the idea instantly made perfect sense to me.

Hal is a scholar and professor of New Testament, most recently at Union Theological Seminary in New York and a founding member of the Jesus Seminar. He has spent decades studying texts from the first two centuries of the Common Era that did not become part of the official canon. Hal has also been Professor of Early Christianity at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College for almost 20 years. Not unlike the way Reconstuctionists view Judaism, Hal views all of Christian tradition as a vibrant, often contested, evolving conversation. Once one embraces the idea of the historical nature of our human efforts to record our spiritual experiences, one wants to hear from as many voices as possible, especially those Barbara Brown Taylor calls "our first forbearers in faith."

Hal is a scholar and professor of New Testament, most recently at Union Theological Seminary in New York and a founding member of the Jesus Seminar. He has spent decades studying texts from the first two centuries of the Common Era that did not become part of the official canon. Hal has also been Professor of Early Christianity at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College for almost 20 years. Not unlike the way Reconstuctionists view Judaism, Hal views all of Christian tradition as a vibrant, often contested, evolving conversation. Once one embraces the idea of the historical nature of our human efforts to record our spiritual experiences, one wants to hear from as many voices as possible, especially those Barbara Brown Taylor calls "our first forbearers in faith."

Hal asked: Why not revisit texts that were revered by at least some early communities who followed Jesus, even if those documents did not make it onto the final list of 27 books? After all, canonization was a very human process, not completed until the fourth century. I had not realized the New Testament was canonized that late, nor did I know much about the over 75 texts that have been discovered in the last two centuries, most famously in 1945 at Nag Hamadi in Egypt. It turns out that there are other gospels besides the four, other letters than Paul's, a secret John and psalms about Jesus. I never knew that the Ethiopian and Syriac churches made different choices. It seemed obvious that the whole question of Christian sacred Scripture could be opened again, with potential to reinvigorate Christian theology, liturgy and spiritual practice.

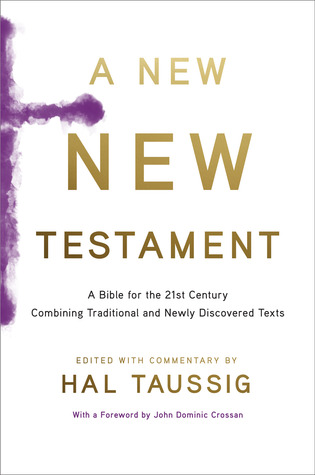

Also obvious to me was Hal's reason for doing so. Hal has spent his entire professional life as bi-vocational, a scholar who continuously served churches as a pastor. So it made sense that Hal's primary motive in undertaking this project was to expand the scope of spiritually compelling resources available to religious seekers. Less obvious, although wonderfully exciting, was Hal's plan. Rather than decide himself which documents to include in a new new testament, he would convene a council of scholars and practitioners who would make the decision in a communal, democratic process. The piety and humility of this project struck a chord. Tradition would be honored for its accrued sacred quality -- none of the official 27 books would be dismissed. The resulting volume -- the old interspersed with selected new -- would be titled "A New New Testament." As Phyllis Tickle has written, "Every five hundred years, the church needs a rummage sale. Others are now free, indeed encouraged, to offer their own versions."

There was only one detail of the plan that struck me as surprising. Hal was not only sharing with me his excitement about this huge undertaking, he was inviting me to be a member of the council. What business was it of mine, or of Rabbi Arthur Waskow, the other Jew involved, what Christians might find spiritually meaningful? How would I know? I have to confess that my "evil impulse" wondered if I really wanted their New Testament to be any richer than it was. After all, as a rabbi, shouldn't I be playing for a different team? Having squelched that idea as last century thinking, I listened to Hal's wisdom on this matter. He wanted to learn what people today might find meaningful, and he did not want to hear just from Christians. He would also have a yoga scholar on board.

I ended up serving on the executive committee that culled from 40 documents the 20 that the council would consider. I then took part in the February 2012 council that selected the 10 documents that ultimately made it into "A New New Testament." It meant a lot of reading. Some of it was fabulous, like the poem Thunder: A Perfect Mind, the kind of text one might chose to tattoo a verse from on one's body. (I learned that one of Hal's research assistants had, indeed, done just that.) The Gospel of Mary provided exciting reading. I loved The Gospel of Truth with its lush, sensual imagery and its joy. Some of the work, however, was a slog. I found the martyrdom texts rough going. I tried to rouse my enthusiasm for a text about Perpetua, a nursing mother, who met a martyr's death at the age of 22, along with her slave Felicity. Some of the scholars on the Council, in particular women, thought it good to remind Christians of the passion and zeal of the first centuries of their faith, the life or death consequences of living out the message of Jesus. Fascinating as I found the story, it did not qualify as Scripture for me. Simplistically perhaps, it seemed to me that there is too much martyrdom and death going on in the name of religion these days.

The texts we examined are far from perfect, just like the ones in the New Testament itself, or the Hebrew Bible for that matter. The Christians on the Council took utterly seriously their responsibility to bring to people an expanded understanding of their faith, even as they would not airbrush the picture for 21st century political correctness. As Hal writes, "the traditional New Testament binding has broken open." One can try to paste it back together or one can revel in the opportunity -- rereading the old in light of the new, rethinking, reimaging and reconstructing. All of it human and flawed, flawed and human. The intention makes it holy work.