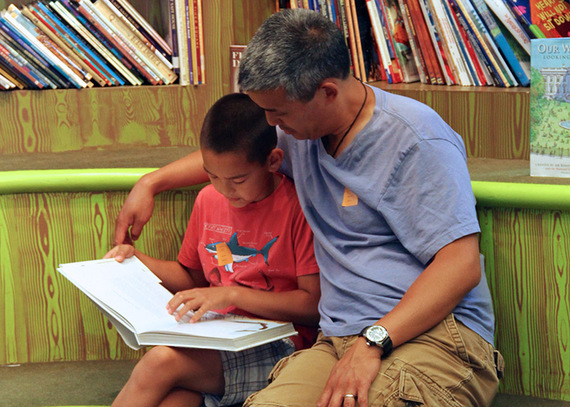

The New-York Historical Society and its partners have created many programs to promote historical literacy among young readers and their families. Many of these programs are hosted on site at the Barbara K. Lipman Children's History Library

We've all seen those "gotcha" TV segments. A man or woman, waylaid on the street, takes an impromptu quiz about American history and fails spectacularly. Who was the first president of the United States? (George III?) Who won the Civil War? (Notre Dame?) These wildly off-the-mark responses can be hilarious -- especially when the question is only slightly more challenging than, "Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?"

But when you go beyond such video anecdotes and learn how much or how little Americans generally know about our own past, you'll probably stop laughing. According to the ongoing National Assessment of Educational Progress, conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, fewer than half of our 12th-grade students have a basic proficiency in U.S. history. Among fourth-graders, it's fewer than a third.

So why do our young people suffer from this history deficit? And what can we do about it?

No doubt one cause of the history deficit is the increasing push for STEM education: training in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Of course we all want our students to have a solid foundation in these subjects, but that doesn't mean the social sciences should be sacrificed. But what happens when STEM instruction, considered necessary to make students qualified candidates in today's competitive job market, forces out the teaching of subjects judged to be less "practical" -- such as U.S. history?

Robert Pondiscio, the executive director of CitizenshipFirst, a Harlem-based education organization, summed up what's being lost when he wrote, "Many Americans have forgotten we have public schools so students can become educated citizens capable of self-government."

Fortunately, this mission has not withered away completely. Even though the place of U.S. history is shrinking, our schools continue to teach social studies and civics. But it's arguable civics classes that are sacrificed -- their content flattened out, their urgency drained away -- when students lack knowledge about the people, events, and institutions forming the foundation of our society. Maybe the low voter turnout in American elections reflects this emptying out of our concept of civics.

And maybe, when U.S. history is taught, we're not doing a good enough job. Ask students about history class, and you're likely to hear one word, over and over: boring. The textbooks and handouts are dull, you'll be told, and the kids simply don't see the connection with their lives today.

So how can we change this?

There have to be many answers -- and one of them might begin with the recognition that an odd thing can happen to kids after they leave school and get out into the world. Many of them develop an interest in history.

Kids can go to the movies to watch Lincoln and Selma. They can go to the theater and see Hamilton. They can turn on the TV and tune in to Wolf Hall.

And what do they read if they want to get absorbed in a novel? The answer, as often as not, is historical fiction. Just look at the current best-seller list: All the Light We Cannot See, The Nightingale, Four Nights with the Duke, and Outlander.

It makes sense. However high or low their literary aspirations, these historical novels work hard to be engaging. The authors' livelihoods depend on it -- and so the curiosity of readers is aroused, their capacity to imagine the past is awakened, their store of information is enriched.

Our question is: Why wait for kids to turn into grown-ups? One way that we could help get students hooked on history today is to put historical novels into their hands -- ones that are both entertaining and faithful to the experience of the past.

And yet, if you turn from the adult best-seller list to the one for children's books, you'll see that the historical titles all but disappear. That's not the kids' fault. To a large extent, the books on this list aren't chosen by the kids but for them, by the grown-ups.

So why don't we adults use our power to choose, and steer early learners and young adults toward high-quality books that can make history come alive to them -- and help them come alive to history? This is the principle behind the Grateful American Book Prize, a new prize created by David Bruce Smith, an author, editor, publisher, and business executive based in Washington, DC. This first-of-its-kind award for children's history books, both fiction and nonfiction, places new emphasis for authors and publishers on the importance of engaging early learners in the enjoyment of history. It may not be a complete remedy for America's history deficit -- but it is a novel solution.