My grandmother, who lived well into her 90s, contracted tuberculosis as a young mother. She spent several lonely years in Saranac Lake, New York while her husband struggled to earn a living and her children were shuffled from relative to relative. She was not alone. According to "The Forgotten Plague: The Deadly Story of Tuberculosis and the Hunt for a Cure" -- airing on PBS stations on Feb. 10 -- my grandmother was among the one in every 170 Americans who lived in exile in sanatoriums. She was, however, one of the lucky ones. She survived.

The PBS documentary, part of the American Experience series, is airing during a heated debate over vaccinations and the unlikely reappearance of measles in the U.S. A nasty disease considered by most of us to have gone the way of smallpox, measles has aroused fear and anger nationwide. We all might do well to spend an hour on the evening of Feb. 10 watching PBS to remind ourselves of how infectious diseases can alter history.

Once known as "Captain of Death," or consumption, by the turn of the century TB had killed one in seven people who had ever lived. It was an awful disease which resulted in hacking bloody coughs and overwhelming fatigue. Most physicians thought it was hereditary or caused by living in crowded cities. In the mid- to late-1800s, people with consumption fled west to the barely developed communities of Albuquerque or Denver or Los Angeles. Others went to the mountains or beaches where "invalids" and "health seekers" were welcomed. But the idea that these people were infectious never occurred to anyone.

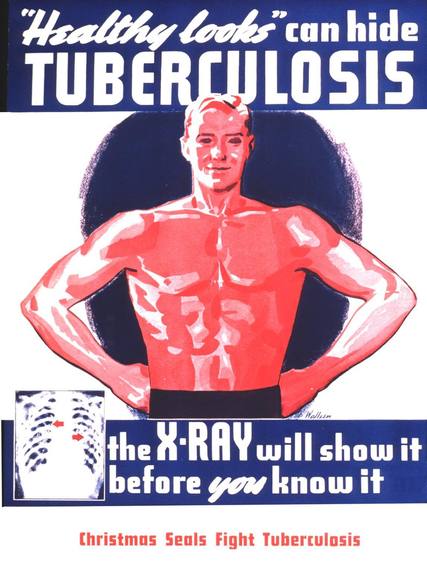

It wasn't until a physician with TB named Edward Trudeau read a study by European scientist Robert Koch that the idea of germs causing disease began to take hold. And even then, it was another few decades before the nation accepted that TB was contagious. Once that was common knowledge, the first public health campaign in US history began in earnest. Posters and signs went up warning people about coughing and spitting and sneezing. Women's fashions were changed by raising hemlines to keep skirts from touching bodily fluids in the streets. Men were cautioned to trim or remove their whiskers which might harbor bacteria.

And, of course, stigma followed. People with TB were quarantined or sent away, though many communities scrambled to keep them out. Sanatoriums were built, most famously in Saranac Lake. Parks and playgrounds were built in large cities to give all citizens a place to take in fresh air. But, as with many public health crises, immigrants were twice as likely to die and African-Americans three to four times more likely to die of the disease than white people.

Although penicillin became available in the early 1940s, it was not an effective treatment for TB. Fortunately, by 1944, streptomycin became available for treating the disease and was soon followed in the late 1940s by a cocktail of antibiotics that effectively ended the disease that had plagued humanity for over 3,000 years. Or did it? I never thought I would be hearing about measles in the 21st century. So perhaps we should all watch this program as a reminder that the dangers of the past require us to be ever vigilant and never say never.