Across the Global South, there is a slowly growing understanding that nobody can know the challenges and needs of the urban poor better than the urban poor themselves. The voices of low-income residents are essential to creating smart, inclusive development policies and projects. In many cities, however, poor communities have had to fight to convince governments to see them as potential collaborators, rather than simply objects of top-down development programs. In Rio, Delhi, Lilongwe and Cairo, initiatives to forefront community voices are on the rise, and we examine four cases in which poor communities demand the right to participate and be heard.

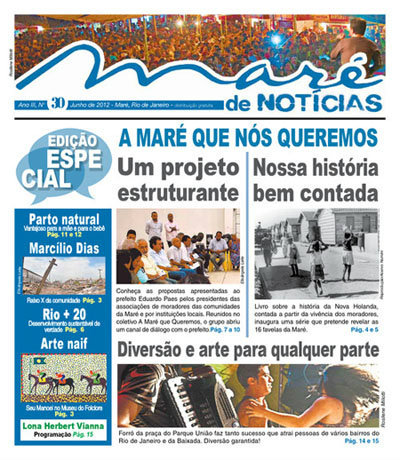

In Rio, the civil society organization Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré links people and institutions in order to implement structural transformation projects in one of the city's biggest favela. Aiming to strengthen the locality as a whole, the organization has created unified discussion forums, a newspaper, a library, research centers, language and professional courses, cultural centers and festivals. Redes promotes two types of dialogues: one, with social agents, that brings community residents together and highlights priorities and interests; the other, with government officials, that demands rights, investments and actions for the benefit of residents. When negotiating with the government, the organization often encounters authoritarian behaviors, indifference and clientelism (the practice of exchanging gifts and favors for support). Furthermore, the lack of access to quality education and political training for local leaders can hinder efforts to bring about change, but Redes' leaders and staff remain determined to continue working for the interests of their communities.

In Rio, the civil society organization Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré links people and institutions in order to implement structural transformation projects in one of the city's biggest favela. Aiming to strengthen the locality as a whole, the organization has created unified discussion forums, a newspaper, a library, research centers, language and professional courses, cultural centers and festivals. Redes promotes two types of dialogues: one, with social agents, that brings community residents together and highlights priorities and interests; the other, with government officials, that demands rights, investments and actions for the benefit of residents. When negotiating with the government, the organization often encounters authoritarian behaviors, indifference and clientelism (the practice of exchanging gifts and favors for support). Furthermore, the lack of access to quality education and political training for local leaders can hinder efforts to bring about change, but Redes' leaders and staff remain determined to continue working for the interests of their communities.

In Malawi, the Federation of the Rural and Urban Poor works with informal settlements in all four of the countries' main cities, including Lilongwe. The Federation mobilizes local communities to conduct enumeration surveys and uses them to develop Community Strategic Plans (CSPs), which list priorities of the communities. The communities then organize meetings with stakeholders in the city, where they get to share their findings and plans. The communities have also produced booklets of the CSPs, which they share widely with various agencies. They use the CSP booklets as conversation currency in pushing for their demands. Platforms like Public Square, a monthly radio program that hosts panels with residents of informal communities alongside government officials or service providers, offer opportunities for residents to bring the CSPs and their demands to the attention of radio audiences and the government agency participants.

Evictions related to redevelopment of slums have recently held sway as one of New Delhi's hot button issues. The capacity of a community to articulate alternatives to evictions and gain access to decision-makers is crucial. The Hazards Centre worked for two years with residents of the Kathputli Colony community, who faced threats of eviction, to convince the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) to abandon the plan for removals and opt for a more inclusive alternative redevelopment plan. Residents approached the Hazards Centre for help in understanding a contract between real estate developers and the DDA; the contract appeared to give substantial land to developers while only re-housing some of the residents. The Hazards Centre organized discussions among similarly-threatened communities, arranged legal support and negotiated opportunities for residents to communicate with the DDA. In April 2015, the DDA admitted that its original plan lacked community participation; residents are currently drafting their own redevelopment plan to share with local authorities.

Evictions related to redevelopment of slums have recently held sway as one of New Delhi's hot button issues. The capacity of a community to articulate alternatives to evictions and gain access to decision-makers is crucial. The Hazards Centre worked for two years with residents of the Kathputli Colony community, who faced threats of eviction, to convince the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) to abandon the plan for removals and opt for a more inclusive alternative redevelopment plan. Residents approached the Hazards Centre for help in understanding a contract between real estate developers and the DDA; the contract appeared to give substantial land to developers while only re-housing some of the residents. The Hazards Centre organized discussions among similarly-threatened communities, arranged legal support and negotiated opportunities for residents to communicate with the DDA. In April 2015, the DDA admitted that its original plan lacked community participation; residents are currently drafting their own redevelopment plan to share with local authorities.

Youth constitute a quarter of the Egyptian population, but they rarely participate in policy-making, or collaborate with the government to solve problems. In 2013, the Ministry of Housing launched an innovative initiative called "Our Youth Can Do." The project aims at developing informal areas in Cairo, starting with four districts in which local youth will have a say in development plans. The program encourages youth volunteers to share their opinions of the targeted areas' needs, tools, requirements and methods of development, both in order to design the best redevelopment plans and also to grow the youth's self-confidence. Over 250 young volunteers work hand-in-hand with selected service delivery partners to conduct cleaning, lighting, planting and painting projects, and maintain street platforms. Moreover, a number of privately-owned Egyptian TV channels pledged to follow the achievements accomplished by youth during the campaign, shining a spotlight on the potential of the youth to bring about positive community change.

Check out more of the discussion on finding a voice in the politics of urban poverty on URB.im and contribute your thoughts.

Photo credit: Hazards Centre, Jornal da Maré.