Imagine if in It's A Wonderful Life, Mr. Potter had actually prevailed and George Bailey, a ruined man, had to relocate.

That couldn't happen in a Frank Capra movie, of course, but sadly it can and did happen in real life, at Carnegie Hall, and without that much fuss or fall-out.

Photographer Josef Astor's new documentary, Lost Bohemia, which opens this Friday at Manhattan's IFC Center (and for you non-New Yorkers out there, will also appear soon on DVD) tells this fascinating, revealing tale. And anyone concerned with the role of art and artists in modern society should see it.

First, some background, which starts with a humbling admission.

As a native New Yorker, I've attended numerous Carnegie Hall concerts; I even appeared on its stage once. That said, I had little to no idea about the special world above its stage, formerly known as the Carnegie Hall Studios.

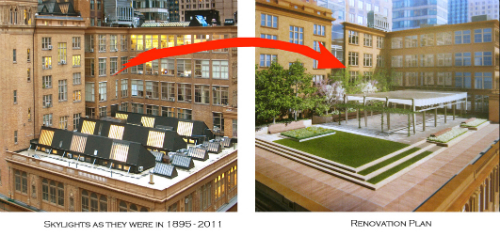

In 1895, these studios (165 of them to be precise) were constructed above the newly completed concert hall as residences and teaching spaces for musicians, painters, photographers, dancers, poets, writers, actors and designers.

And indeed they served admirably in that capacity for a little over a century. As "Lost Bohemia" makes abundantly clear, the history made in that space, which few non-artists even know about, is astounding.

What precisely happened there?

Mark Twain wrote. Enrico Caruso made his first record. Charles Dana Gibson invented the "Gibson Girl". Living affordably in their own private spaces, Isadora Duncan danced, Leonard Bernstein composed, and both John Barrymore and Marlon Brando rehearsed their lines.

Among the other artists and writers who honed their craft in the studios: George Balanchine, Martha Graham, Bob Fosse, Norman Mailer, Paddy Chayefsky, Cecil B. DeMille, Spencer Tracy, Elia Kazan, Marilyn Monroe, Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Jane Fonda, Jason Robards and John Turturro.

If these walls could talk, indeed.

When Josef Astor, a noted photographer who moved into the studios in 1985, started to film Lost Bohemia over a decade ago, his purpose was not only to celebrate the rich history of the place, but also capture the special bonds and camaraderie shared among his fellow tenants.

To that end, we first meet a host of colorful characters among the studios' long-time residents, including Bill Cunningham, photographer for the New York Times (and subject of his own documentary, Bill Cunningham New York; writer Andrew Bergman of Blazing Saddles fame; singer Jeanne Beauvais, who entertained Judy Garland after the latter's historic concerts downstairs, and pianist Don Shirley, who'd host Duke Ellington and Count Basie after their gigs.

Perhaps most memorable among this tight-knit group is photographer Editta Sherman, a spry, spirited lady in her mid-late nineties, often called the "Duchess of Carnegie Hall" for having lived and worked there for over six decades.

Then, as often happens with documentaries, breaking events take Astor's film in an unexpected new direction.

Without a word of warning, in 2001 eviction notices started appearing on residents' doors, and soon enough, the Carnegie Hall Corporation makes it official: studio residents are to be relocated, and the Studios themselves knocked down for eventual conversion into enhanced teaching spaces and administrative offices.

Captured by Astor's camera, what ensues is a noble but futile legal battle for the artists to maintain their homes and work-spaces against a calculated, implacable, well-funded effort to remove them and in effect, systematically demolish all that they-and the studios-stood for.

In their resistance, the residents are up against the imposing figure of Sanford ("Sandy") Weill, former Citigroup chairman, who chairs the board of Carnegie Hall. (Mr. Weill may smile more than Lionel Barrymore's "Mr. Potter," but when it comes to hard business, he may be an even tougher customer.)

It seems Mr. Weill and his posse have lined up city officials to do their bidding in advance; even considering all he's done for New York, let's not forget our current mayor is also a sober man of business.

Since the city technically owns Carnegie Hall and leases it to the Corporation, the Bloomberg Administration could have interceded, but even after appeals from some of the city's most prominent artists and architects, the folks at Gracie Mansion sat on their hands. (Ironically, when Carnegie Hall itself was first threatened with extinction back in 1960, the city ended up buying the structure and giving it landmark status, in order that it be protected).

In addition, apparently Mr. Weill saw nothing improper in awarding the renovation contract for the studios to the architectural firm, Iu + Bibliowicz, even though its principal, Natan Bibliowicz, happens to be his son-in-law.

Lost Bohemia plays out this tragic contest, whose outcome is never in doubt (indeed it feels rigged from the get-go), all the while maintaining its human focus, capturing the emotions and attitudes of the victimized residents, Mr. Astor's neighbors, for whom he clearly feels both allegiance and affection.

As do we. And why not?

Endearing and warmly nostalgic as it is, the film did set me to thinking about where we're headed as a culture, specifically in terms of who's prevailing in the age-old struggle between art and commerce.

To me it's pretty evident that more and more, purely commercial considerations are undermining our appetite and desire for what true art really provides: fresh, original perspectives on what it means to be alive and human.

I'm talking about work that challenges established norms and expectations, that may provoke, move, or even mystify us, but regardless, makes us feel and think on a higher plane than our everyday routines and concerns normally allow.

In an age that leaves less time for reflection, art of this kind, in whatever form, would seem like a vital antidote to the numbing superficiality pervading our culture. And yet it's only getting harder to find.

Look at our own country. In resource terms we still outstrip our European counterparts, yet I'd argue they show a more pronounced respect and reverence for serious art and culture than we do.

Italy and France, to name but two examples, view the arts as an integral part of their identity and history, and so allot public funds to support their finest and most promising practitioners.

Meanwhile, any effort to do the same thing here smacks of socialism.

While we lead the world in light, escapist, bubble-gum entertainment, we have gradually de-emphasized anything more demanding than a comic book movie, a reality show, or a Chelsea Handler bestseller. We have more TV channels, but less intelligent programming, than ever before. PBS once again is under threat of extinction, and most not-for-profit arts institutions face significant challenges.

And inevitably, we marginalize the artists themselves. The word "bohemian" actually means a "socially unconventional person, especially a writer or artist", and watching the film, you recognize swiftly that this descriptor truly applies to most of the Carnegie studio residents profiled in the film; there are no household names to be found.

That said, how many artistic geniuses never experienced a hint of recognition in their lifetime? (Van Gogh and Poe immediately spring to mind, but it's a long list.)

Artists who create work ahead of their time have always suffered, but somehow they've still always been driven to create. One wonders: if the very concept of serious art is increasingly devalued, will the Van Goghs of tomorrow even be moved to pick up a brush in the first place? And what price do we pay if they don't?

In addition, though the combined assets of the last studio residents might not look so hot on a balance sheet, so what? All of these people created great work in their own fields, and contributed to the vibrant arts culture that's traditionally defined this greatest of cities. Who can put a figure on that?

In the end, the Carnegie Studios made it possible for them to live as true bohemians: to enjoy the freedom of being deliciously different and quirky in outlook, joyous and often flamboyant in spirit. That freedom in turn informed and inspired their work.

I suppose it was simply too good to last.

I do think it's a blessing that violinist Isaac Stern, who was instrumental in saving Carnegie Hall back in 1960, did not live to see this happen.

In his own time, he referred to Carnegie Hall -- and by extension its fabled studios -- as a "crucible of democratic creativity... bringing together all that is best in America's myriad ethnic and cultural strains... proving that we have built not just a nation but a civilization."

Sounds quaint, doesn't it?

For a fond and stirring tribute to a grand tradition and a fading way of life, by all means see Josef Astor's Lost Bohemia.

For the best movies available on DVD, visit www.bestmoviesbyfarr.com

To see John's videos for WNET-Channel 13, go to www.reel13.org