As we drive to Hebron, I discover that my guide Yehuda Shaul, a cherubic-looking Orthodox Jew with a generous, brown, full beard, and yarmulke, is likely to play down the horror of a situation with a characteristic mischievous shrug. Yehuda is kind enough to be pouring over a map of the West Bank with me as we drive on the Jewish highway through the West Bank. "What do you mean, Jewish Road??" I ask. Yehuda laughs his "Oh-you-don't-know-the-10th-of-it" kind of laugh that I've come to love.

Yehuda got to know Hebron when he served there as an Israeli soldier, a military service he increasingly found unethical, absurd, impossible, then a horror. When he finished his mandated tour, he started an explosively controversial group called Breaking the Silence, which takes the testimony of IDF soldiers who served in the Occupied Territories and found the need to talk about ways that it violated their ethics, training, and/or religious principles. It also gives tours of Hebron, like the one I was about to go on.

The road we are driving on, the infamous 443, cuts through the West Bank and goes from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. It is dotted frequently with medieval looking fortresses, though moat-less with white cement walls branded with huge Hebrew letters. These are the settlements. Yehuda drives me through one. It is pristine, a Weeds-Agrestic-looking suburbia, with synagogues and yeshivas, pizzerias, bus stops, kosher butchers, and schools. It teems with children.

Closer to Hebron on our trip through the West Bank, I ask Yehuda about a tunnel dirt-like road that I see below us on road 443. Yehuda tells me that is the road the Palestinians take to Nazareth and Ramallah to do their trade, since 443 is closed off to them. I am appalled. "What can be done?" I ask. He laughs. "That road is a great success story! It took years of pressure to get that tunnel road."

He goes on. "Israeli citizens were shot driving on 443 in 2002, so it was shut down to them, but Palestinians can't work and live without this road. So they sued the Supreme Court, and they ruled in their favor in 2009. But this," he says, looking down, "is how the generals would like to run things." He and his Palestinian cabdriver (who is fluent in both English and Hebrew) laugh what I came to know as the Hebron laugh of diminished expectations.

"Now look at the map."

He is holding in front of me a Btselem map, with regions called A zones (the Pal-controlled section in the West Bank) and C zones (the Israeli-controlled section in the West Bank), which I labor to understand. The upshot of this complicated map is that -- over the past eight or ten years -- the tiny West Bank, the heart of the future Palestinian state, has begun to resemble, as far as I can tell, swiss cheese. It is utterly non-contiguous, a piece of Emmerthal dotted with "these settlement Agresticky thingys" -- little, self -- contained suburban/fortresses everywhere.

Right outside Hebron, we stop at one called Kiryat Arba, with a park called Rabbi Kahane Park, commemorating the gravesite of Baruch Goldstein (who slaughtered 29 Palestinians at the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron in '94). It was hard not to be sickened by this demonstration of the celebration of false idols run amok.

We reach Hebron center-square, where The Tomb of the Patriarchs -- sacred to three religions -- is ahead of us. This spot has prompted some of the ugliest battles of the Israeli-Palestinian long wars and some nutter is freaking out on the loud speaker. Yehuda, who never looks horrified, looks horrified, and says he can't believe his ears. He's reluctant to translate, but I press. He tells me that the man is saying that Milosovich is a hero for his slaughter of the Muslims.

IDF soldiers mingle about, tensely.

Yehuda knows I have to see the Tomb so we go in, and he runs into a relative who hates his guts and scowls and grumbles at him for what he is doing. I move towards Sarah's grave and am stunned to see all our matriarchs and patriarchs behind iron bars.

That sets the tone for Hebron. It is eerily empty. Across the street is a sort of mock pleasant tourist scene made up of one, maybe two, souvenir shops for the international visitors to the area, Potemkin Village-like, looking sort of desperate. Yehuda tells me that the protection of the Tomb is led by a designated unit, which indicates how potentially volatile this spot is at all times.

We sit at one of the souvenir shops whose excited vendor calls out to Yehuda, attracting a crowd. First, a travelling group of teen actors from Nablus, all smiles, join us for cokes and tea. The local vendor tells them that Yehuda, this Jew, right there, was IDF in Hebron. I tell them I am from LA. (Somewhat interesting.) The actors want to be photographed with the IDF 'monster' to show their mothers. Everyone hugs for the camera. Then come some professional West Bank-torture-tourists-activists-Irish, English, ladies in their late 60's - all of whom want to walk Hebron with Yehuda; then some T.I.P.H. (link) UN observer types from Norway (of course). Soon it is time for Yehuda and me to face the music -- not the friendly five or six Palestinians who haven't been forced out of downtown Hebron. Not potential Hamas or Fatah terrorists. Well, who knows? That has been known to be a real problem, thus the high-ranking IDF commander outside. But the ones we will be facing down today are THE LOCALS.

I tell them I am from LA. (Somewhat interesting.) The actors want to be photographed with the IDF 'monster' to show their mothers. Everyone hugs for the camera. Then come some professional West Bank-torture-tourists-activists-Irish, English, ladies in their late 60's - all of whom want to walk Hebron with Yehuda; then some T.I.P.H. (link) UN observer types from Norway (of course). Soon it is time for Yehuda and me to face the music -- not the friendly five or six Palestinians who haven't been forced out of downtown Hebron. Not potential Hamas or Fatah terrorists. Well, who knows? That has been known to be a real problem, thus the high-ranking IDF commander outside. But the ones we will be facing down today are THE LOCALS.

We begin our long walk through the calamitous town. Yehuda tells me this town was bustling with Palestinians in 2000, before the 2nd intifada. In (the Israeli controlled) H2 where we are walking, the security precautions are so tight that the main road (formerly the main Palestinian market) is now restricted to Jews, and we see practically no Arabs and no Arab businesses still open. In H1, in which the PA has control, it is a different matter. But that's not where we are.

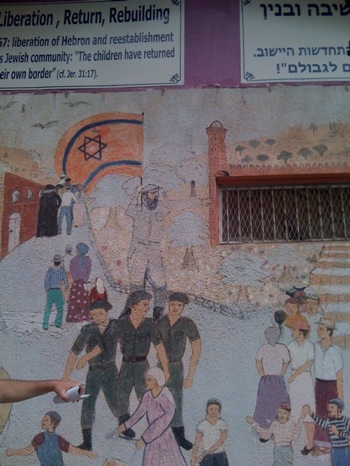

The settler control has come in stages. Some of it historic in the settler movement. Yehuda tells me the history as we walk the empty streets looking at the radical-right wing graffiti re-enacting the history of settler victories in Hebron since the massacre of 1929, and we begin to attract the attention of what seem like the enforcers for local settlers in four-wheel vehicles with the windows blacked out, like buzzing hornets.

We continue our walk down the streets, which are covered with glass from broken windows, and pass the once thriving Arab market, now closed and shut down. We make our way through empty streets, up hills, and meet a group of soldiers, who ask to see our papers. They have been alerted by a local settler group who saw us walking down the street and didn't know who we were. (Why should they have to?)

A short digression is needed here, on why I was not hostile when approached by these IDF soldiers. I knew who to be hostile to: the buzzing security vehicles of the hidden urban settlers who had alerted them, as opposed to the maligned foot soldiers of Jenin, Gaza and Lebanon.

The prior day at the Magellan base was unexpectedly wonderful, I have very recently come to know the Israeli soldiers. I fell in love with the young kids training in the IDF. I hadn't even wanted to go. As I wrote my brother, "Who knew I'd find the soul of Israel in the IDF? But they are the best of Israel."

I was greeted by a room full of gorgeous (one was Miss Israel, so I'm not exaggerating) 18-20 year old girls in uniform, talking away about where they came from and what squadron they were from and what they did in the army and what they were going to do when they got out. We talked careers and purpose and how the Army affects that and whether that makes them different from kids their age in the US. Then I went to the guy's dorms, drank their Turkish coffee, and talked politics. They were so happy they were going home to their parents that weekend.

We talked for so long that the boss Army guy had to break it up for weapons practice. The gals train the men in weapons use and practice -- I wondered what would happen here if guys were exposed to girls training them early in life. The way they related to each other -- we're equal, no biggie -- was thrilling to me.

It was the sexiest version of MASH (Hebrew/English style) I had ever seen. The difference was, it was my son, your daughter, me or any kid I had ever grown up with. For the first time in my visit Israel was familiar to me, through its children and their idealism and service. This is the age I love kids. These were not the 'monsters of Jenin.' This army has been calumnized. These were my children. So...

Back to Hebron: Yehuda, whose work here began after his time in the military, is also not hostile to soldiers between a rock and a hard place.

This was the context in which we spoke to them. We understand the situation of soldiers in an absurd occupation and asymmetrical war. They thought the guys complaining about us were jerks (putzes was the exact word).

We say good-bye and keep walking. I take a picture of a bizarre painting on a wall of an ultra-religious anti-secular Zionist flag that was really strange.  Another hostile settler car whizzes by. A security car for an urban settlement asks what we are doing there. They do not like me taking pictures. Yehuda says we have every right to be there. Note that we are walking on streets only Jews can walk on. All these bizarre-like rules come from security concerns, not racial laws, which is why it is not a apartheid, even though the shame of walking on them feels that way.

Another hostile settler car whizzes by. A security car for an urban settlement asks what we are doing there. They do not like me taking pictures. Yehuda says we have every right to be there. Note that we are walking on streets only Jews can walk on. All these bizarre-like rules come from security concerns, not racial laws, which is why it is not a apartheid, even though the shame of walking on them feels that way.

Part of the Breaking the Silence tour of Hebron.

We walk uphill on the paved Jewish streets, and come to the now infamous street of what the military calls "The Caged House." Here we turn left, up to what turns out to be a hill of trouble. It has its own narrative, and it is so volatile it has its own checkpoint, where Yehuda and I have our own little drama. Yehuda did not prepare me for our ultimate destination.

One side of this scary hill is a small Brooklyn-based radical settlement, named for the area called Tel Rumeida, which looks like a Topanga Canyon Ranch house. Directly across the street is a checkpoint. Almost next door to the checkpoint is a house, still lived in by the Abu Eisha family. It is now covered in iron bars like a batting cage: the Caged House. The Abu Eisha family, Hebron natives, protected their Jewish neighbors during the 1929 massacre and they now must hide in isolation behind terrifying iron gates to live safely in their familial home. Whither progress, one must ask. Yehuda is not smiling his diminished expectations, shruggy smile when he tells this story.

As we walk up the hill, some children of the settlement are playing on the dirt road. I talk to them, mom-like. Their mother screams from the redwood porch that surrounds her house. With laundry in her arms, "Are you an Arab or a Jew?" "A Jew who doesn't..." I stopped. Yehuda looks at me and says, "Don't answer, she is trying to engage you."

"Traitor!!" she screams. Meanwhile, at the checkpoint, the soldier is telling Yehuda that we can't go any further. Yehuda is getting very irritated and trying not to show it.

"I like all people," I am saying sweetly to her son. He looks at me with a rock in his hand. Yehuda pulls me by the arm. At the checkpoint, the soldiers want our papers. I have to turn over my passport. They were told we are spies, traitors -- by the settlement people. We are being detained. (Well, not literally, but we might be thrown out of Hebron, and then we couldn't go anywhere. Well, we didn't know that.)

He is calling his lawyer and this could take a while. The worst thing I could do is to give he,r and them, a real pretext for holding us. "Are we under arrest?" I ask. Could they actually hold us? "I don't know what they can do because right now they are acting on behalf of this settlement, not the Israeli government. That's what is so wrong about the army here. It isn't clear who it's working for," Yehuda answers.

I resist both the urge to debate with the crazy lady (a weakness of mine, I engage with crazy people), and stick my tongue out at her spoiled child, until Yehuda's lawyer talks sense into the check point person, and we continue behind the Caged House, up the hill and over the hill onto Palestinian land. I will not resist the temptation to say dale as I have no idea where we are going. The houses thin out and we are kind of in a park, or a stony wooded area. We walk up a steep ravine, and suddenly we are in a cement garden. It was clearly once a beautiful fruit garden. There are risers with cushions laid out to sit on, and Issa Amro appears to greet us. The destination of this long schlep became clear.

You can immediately see how and why Issa has become the intermediary and spokesman for the local population. His English and Hebrew are fluent (I can attest to the English); he is charming, well informed, knowledgeable and practical. He is a grass roots kind of guy and yet he is involved with a local theater and film troop (isn't everyone?). He films writers, actors and directors as they tell their stories. He also takes them to... Israel! It was psychologically healing. It replaced the aimlessness the kids were feeling and was politically practicable. It is great for them to meet actual Israelis and demystify their hatred. Work and talk. That's what happened to Issa, when he started working with Yehuda! Now he likes a Jew! A friend joins and says "Me too!" and starts to laugh, we all laugh. He is fun! And he doesn't even offer me a DVD. No hustling in the Occupied Territories.

But there are matters at hand. His close, fond neighbor has had a notice that his land will be impounded because something in his backyard is needed for Israeli security. It has to be fixed by Wednesday, but he received the notice on Friday... Monday is a state holiday so he has only one day to plead his case. They both laugh the Hebron gallows laugh. "Very clever, those Israelis," they say, and start figuring out what to do. Then there's the matter of the US Rabbis who can help find doctors for the region. The time it takes to get to the local hospital given the Kafkaesque road situation could really use some intervention. It took him over five hours to get a boy with a gaping, bleeding wound to the hospital 5 miles away.

Then he asks me about the Tea Party and midterms!! This is April! He knows so much about US politics, details many people in the US at that time didn't know. It is astonishing. At first I am shocked, and then moved. We think our system is irrevocably damaged (I don't), but he looks to it as the best hope of salvaging his! There is really a way that we are the hope for the world, and we toss that away in our quest for the perfect over the possible.

Looking over the West Bank, which from this vantage of Olive trees and young people sitting and eating in the sun, with a man of true moderation and vision without despair -- and understanding how much he depends on us, that he then and now watches American TV searching for pulses and clues, I was so proud to be American. I had lost that feeling a bit since the election, not as much as many, but a bit. But he restored it with much needed perspective. Now, I am so shamed at the thought of him watching this mosque debate.

He asks me how I think Obama will fair, and if he would ultimately be re-elected. I tell him things I hope are still true. That Barack is going to be ok. That, whatever forces of ugliness are unleashed out there, that they have no one, not one credible candidate to run against him.

What I am thinking now is we have to pull together for others, as well as for ourselves. Because our enemies are so vast and so powerful, and so diffuse, and so disguised. They will do more than dismantle what we have started, even so imperfectly, that has so scared them in 18 short months.

We had tea and said good-bye.

And walked back to April in Hebron.

It's September now and the Obama peace negotiations have begun. The day before they commenced, amid profound cynicism that they would yield anything, Hamas set a bomb off and killed four settlers to derail them. Right outside Hebron. Where else?