Within two days last week we lost two jazz greats, both of whom gave us much more than entertainment. For over fifty years, Abbey Lincoln sang and wrote unflinchingly about a woman's survival in a tough world. On August 14, heart failure took her at the age of 80. The day before, Herman Leonard had died at 87. His instrument was a camera; through it, he looked at jazz figures with a fond but probing eye. Somehow, through the art of still pictures, he made their humanity come to life, while adding a sexy touch of film noir.

I knew both artists. Herman and I were last together in March 2009, at a Los Angeles memorial for another great jazz photographer and a friend to us both, William Claxton. Herman had moved to L.A. from New Orleans, where Katrina had ravaged his home and his massive archive of prints. (His negatives survived, thanks to his manager, Jenny Bagert, who had moved them to a safe place just before the storm.) He'd rallied valiantly, and the news about his plight jump-started a wealth of overdue tributes. From October through June, the hallways outside Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola in Manhattan's Time Warner Center became a Herman Leonard gallery, rife with performance shots that beckoned you into the jazz world of old. In one famous picture, saxophonist Dexter Gordon holds his horn while exhaling a spectacular plume of smoke, a beatific look on his face. Herman's 1955 portrait of Chet Baker appears on the cover of my biography of the trumpeter. Chet's youthful beauty is there, but Herman also caught the troubled glance of a deeply sad young man.

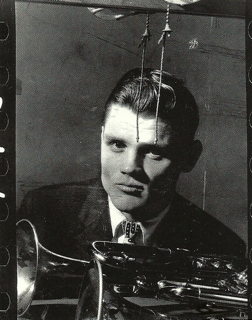

© Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

Herman himself was an upbeat guy whom I never heard complain, despite the fact that he'd known many lean times, including a stretch of near-destitution. He was 82 when Katrina hit. But not even that disaster could break his positive spirit, which included an enormous generosity. In my recent biography of Lena Horne, I used his striking portrait of the singer from 1948. She had allowed him to photograph her without makeup, leaving all her freckles visible. When I saw the finished book, I was heartsick at how poorly the photo had been reproduced. I sent Herman the book with a very embarrassed note of apology. Weeks later, a package arrived in the mail from his office. Inside was a gorgeous oversize print of the picture, inscribed affectionately by Herman, with a congratulatory note that didn't even mention the problem.

© Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

This July I called to say hello. Herman told me matter-of-factly that he was terminally ill; in December his doctor had said he had just three months to live. Here he was over six months later, he marveled, with energy to spare. Two weeks ago I phoned again, and we made plans to meet in California in late September. He told me about his forthcoming book of photos, Jazz, to be published by Bloomsbury this fall. He sounded so confident and full of plans that I still can't believe he's gone.

Optimism didn't come as easily to Abbey Lincoln. Some of her most memorable lyrics - "Bird alone, with no mate/Turning corners, tempting fate," "Straight ahead the road keeps winding, narrow, wet, and dimly lit," "Down here below, I hear the distant thunder and the crying of the blue" - suggest a woman who saw no one to turn to but herself. At the same time, she wrote wishfully of a universe that opened its arms to us all. Her crowning statement was "I Got Thunder (and It Rings)," the anthem of a defiant soul who could withstand anything.

Though Abbey had chosen jazz as her medium, her singing had almost no rhythm; she declaimed songs in broad, lashing strokes and the band followed her lead. I first saw her in 1990 at the Regattabar, a jazz club in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She closed her show with "Live for Life," a buoyant French movie theme of 1967. For Abbey, the song was too sagely to be raced through; I can still remember how she pored over the lines, "What is real is what is here and now/The here and now is all that we possess!" with fists clenched.

I scrambled to get her every recording. The one that captured me most was Straight Ahead, a searing document of the black struggle, made in 1960. Leading the band was her then-husband, the pioneer bebop drummer Max Roach. Later I read of how violently those two fireballs had collided before their 1970 divorce. I learned of all the times Abbey had been dead broke; she'd even lived in an apartment above someone's garage. She sang for thirty-five years with no major breakthrough. Then Verve Records signed her in 1990, and she was hailed widely as a long-neglected master.

In 1994, the New York Times Magazine accepted my proposal for an Abbey Lincoln feature, and I went to her large Harlem apartment to interview her. The walls were covered with Lincoln's paintings, and unfinished ones sat on easels. Half-written poems rested on tables, drafts of lyrics on the piano. Solitude hung in the air. Press campaigns had depicted the singer as a long-suffering freedom fighter, now finally at peace. But as warmly as she received me, I felt no contentment in Lincoln, whose heavy drinking was no secret. When she recalled certain names and episodes from her past, anger welled up in her so fiercely that her nostrils flared and her eyes blazed. That intensity mesmerized audiences, but if you were alone in a room with her it could be suffocating.

The Times Magazine killed that piece, and I didn't have the heart to tell her. She found out anyway, and called to console me. "I know how it feels when somebody makes you a promise and doesn't keep their word," she said.

In recent years, the ultimate angel of jazz musicians in need, Wendy Oxenhorn of the Jazz Foundation of America, had gone to extraordinary lengths to make the ailing singer's life more comfortable. One afternoon, Wendy invited me to join them for lunch at an outdoor café near Abbey's apartment. The singer was in uncommonly bright spirits as she clutched Wendy's toy poodle; she was still heartbroken over the recent loss of her own dog. I effused to Abbey over all she'd meant to me, and she clearly enjoyed it. Wendy explained to me afterward: "She responds to the attention of a man."

But I couldn't cheer her up a few months later, when I made a visit, alone, to Abbey's apartment. By now her sense of hopelessness was overwhelming; every worldly force, she felt, was conspiring against us. Grasping for encouraging words, I spoke of all the lives she'd touched, and how her CDs would inspire people forever. She managed a pained smile, and her eyes welled with tears. Her last great dream, she explained, was to turn her apartment into a shelter for needy musicians. She would call it Moseka House, based on the African name she'd once adopted, Aminata Moseka.

After I left, I reflected on how this woman who had uplifted countless people seemed so unable (or unwilling) to embrace joy. But in her final months, Wendy assures me, Abbey was "very much at peace." Partial dementia had eased her negativity, while Wendy and other friends had convinced her that she would not be forgotten. Photographer Carol Friedman's long-in-the-works documentary, Abbey Lincoln: The Music Is the Magic, will probably appear soon. Through that film and her CDs, Lincoln's work is here to stay. She searched out the truth, and expressed it as deeply as anyone in jazz ever has.