As the 115th Congress begins its efforts to dismantle the Affordable Care Act (AAC) while promising "a stable transition to a better health care system", it is timely to review what exactly ACA was able to achieve so far in its 6+ years of existence. And why ensuring access to timely affordable and quality healthcare is critical to this nation's competitiveness and... no pun intended... economic health.

The cost of healthcare is, and continues to be, a principal concern of many US citizens. A recent Gallup poll indicated that healthcare costs top U.S. families' financial concerns; fully 15 percent of Americans stated that healthcare costs were their family's top financial concern. Greater than the 13 percent who considered lack of money/low wages, the 9 percent who worried about not having enough money to pay debts, the 9 percent who worried about college costs, and the 8 percent who considered the costs of owning/renting a home as their top financial priorities.

Who experiences trouble paying medical bills? A recent analysis reminds us that while significant proportions of the uninsured (53 percent) and the disabled (47 percent) are experiencing problems paying medical bills, this is an issue also for those individuals who earn less than $50,000 a year (37 percent) and even those earning $50,000 to $100,000 a year (26 percent). And having private insurance has not been the answer-all, as 26 percent of those who have private insurance with high-deductible plans and one-fifth (19 percent) of people with private insurance overall (19 percent) experienced problems paying medical bills in the past year.

The ACA signed into law March 2010 which among many other actions, expanded access by increasing insurability, and the subsequent June 2012 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court upholding the individual mandate while essentially making Medicaid expansion optional for individual states, created a natural experiment on the impact of legislation and insurability on health coverage and wellness outcomes. It is an experiment whose data is still being generated. But what have we learned so far?

Firstly that the ACA, as political and regulatory instrument, has been successful at achieving its immediate objective... that of reducing the number of uninsured. Roughly in the first quarter of 2016, there were 8.6 percent of Americans -- or about 27.3 million people -- who were uninsured, the first time in history that the nation's uninsured rate fell below 9 percent. In 2010, the year that the ACA became law, 48.6 million Americans, or 16 percent of the population, lacked health insurance. Thus, passage of the ACA has cut the uninsured rate by almost half and the trend seems to be continuing.

However, it is also clear that between 24 and 27 million American adults remain uninsured, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund. A closer look at those who remain uninsured, such as the one drafted by the New York Times, is instructional in the setting of this natural experiment on the impact of legislation and insurability on health coverage. Firstly, they are increasingly Hispanic. In fact, 40 percent of the uninsured today are Hispanic, although the overall uninsured rate among this ethnic group has fallen to 29 percent, from 36 percent in 2013. However, we should also note that being uninsured is not only the problem of ethnic minorities or immigrants, as 41 percent of all uninsured are non-Hispanic Whites.

Almost half of the uninsured are young (ages 19 to 34 years), although again in this group the percentage of uninsured has also decreased, from 28 percent in 2013 to 18 percent currently.

And almost 40 percent of the remaining uninsured have incomes below the federal poverty level (i.e. $24,250 for a family of four), which conversely means that 60 percent of the uninsured do not fall in this category. In fact, as I have commented previously most of the uninsured are employed and work. About 57 percent of Americans who remain uninsured have jobs and most of these (57 percent again) work at small companies with fewer than 25 employees; companies that are exempt from ACA's requirement that employers offer health insurance to their full-time workers or pay a fine.

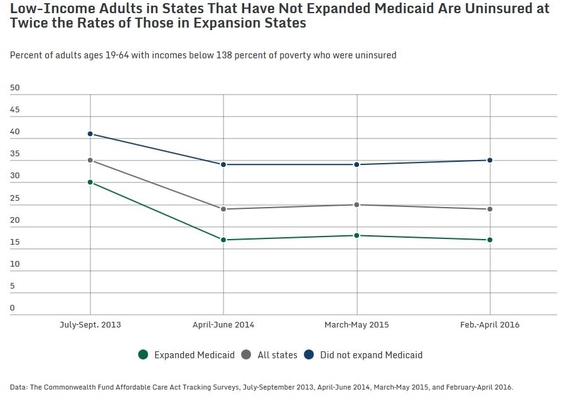

Finally, and most telling, the uninsured rate among adults with Medicaid-eligible income levels (under 138 percent of poverty) has fallen by half (from 30 percent in 2013 to 17 percent in 2016) in the 30 states and the District of Columbia that had expanded Medicaid at the time of the survey. The uninsured rate in this group of people in states that did not expand Medicaid funding declined only slightly and, at 35 percent, was the rate of Medicaid-eligible adults in expansion states.

Not surprising. A recent study has estimated that 63 percent of the gains by ACA in lowering the uninsured rate were achieved through Medicaid, with the other almost 40 percent attributable to the law implementing premium subsidies for coverage purchased on the newly created insurance exchanges. Thus, is clear that where the full impact of ACA was curtailed, either by regulation or state choice, the number of uninsured remained relatively high despite the availability of federally-managed insurance exchanges.

But what about health outcomes? While it seems now obvious that the implementation of the ACA achieved a significant lowering in the number of uninsured, particularly in states and in industries subject to the full impact of the regulation, what is more important is the answer to the question "Did decreasing the rate of uninsured improve the health of the insured and that of the nation?" And here the data is still scant, but suggestive. In an interesting analysis, Sommers and colleagues compared various health outcomes in two states where Medicaid was expanded under ACA (Kentucky) or Medicaid funds were able to be used to purchase private insurance for low-income adults (Arkansas) vs. a state where no such expansions were allowed (Texas). The investigators noted that by the second year of expansion, Kentucky's Medicaid program and Arkansas's private option, relative to the Texas non-expansion experience, were associated with significant increases in outpatient utilization, preventive care, and improved health care quality; reductions in emergency department use; and improved self-reported health. In another study ACA Medicaid expansions were associated with improved quality of coverage, increased utilization of some types of health care, and higher rates of diagnosis of chronic health conditions for low-income adults.

Thus, while it's too early to tell, and much needs to still be addressed, early results from the ACA 'natural experiment' suggest that it has done what it set out to do. That is, it has resulted in a significantly reduced rate of insured. And there are early, albeit still tenuous, signs that suggest that these reductions in the uninsured rate have resulted in improved individual medical and financial health. But like all experiments this is one whose outcome is not yet a certainty. These are lessons that the 115th Congress, while aiming to repeal ACA, should keep in mind as they craft and roll-out their promised health care reform replacement plan.