Undoubtedly, I'm biased. I never subjected myself or my marriage to any fertility treatments. But after my first child, Liala Ljunggren, died the day after her due date, a full-term stillborn gorgeous baby girl, I spent two years on the rollercoaster of trying to get pregnant again: transforming sex into a purely utilitarian act and weeping every time my period came. I remember reading news stories about abusive parents whose destroyed children had to be removed from their care and literally wailing out loud, pleading with the stony, unresponsive universe, "I wouldn't have done that, I promise! Won't you just give me a chance, please?" I ranted and raged, jealous of all the women around me who had no trouble getting pregnant, indignant at the unfairness of it all. I felt possessed and desperate. To put it mildly, those two years, both attempting to recover from the loss of my daughter and to get pregnant again, were tough.

I wasn't alone in struggling to get pregnant. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 11 percent of American women in their reproductive years (age 15-44) suffer from infertility. Myriad intervention options increase the odds of pregnancy followed by a live birth, with costs ranging from as low as $60 to over $100,000 and odds from 15 percent to 50 percent of one treatment culminating in a live baby. From artificial insemination to zygote intrafallopian transfer, there's literally an A to Z list of options that promise both to screw with a woman's body, inducing all sorts of side effects, and challenge the strongest of couples to survive a process that is fraught with uncertainty and carries no promise of a perfect ending.

Yet, given my experience as a parent, of both a birth-child and adopted children, I can't help but wonder why people who are struggling with fertility subject themselves to the complications, expense, and potential health risks of birthing a genetically related child without seriously considering adoption.

Yes, it's a biological imperative to reproduce. Yes, it's "natural" to want our offspring to look like us, act like us (do we really?), think like us. Yes, it's comforting to know what we're getting when we give birth, that our genes will be passed on. Having said that, we are deluding ourselves if we think that we can predict our children's personalities and proclivities, or believe that our families' genetic profiles are pristine. What family history lacks the heartbreak that derives from birth defects, criminal behavior, mental illness, or potentially life-threatening, life-shortening, or otherwise debilitating conditions? If only we were immune from our family's messy past!

I've heard the argument that truly loving someone who doesn't share your genes is impossible, but every legal spousal relationship defies that declaration, so don't go there.

But what about all the things that could go wrong with adoption? How do you know you'll love the child enough? Or that the birth-mother won't change her mind and come back to claim what was hers? Or that the rest of your family will accept your decision? It's easy to let the more obvious risks of adoption blot out the less visible ones that accompany pregnancy and childbirth.

In my case, things sorted themselves out over time. I did get pregnant, and my first son managed to make it into the world in one lively, noisy piece. Four days later at his first post-partum checkup, however, my doctor grimly informed me that my newborn had nearly followed in his older sister's footsteps. Clearly, pregnancy didn't agree with me, or my babies.

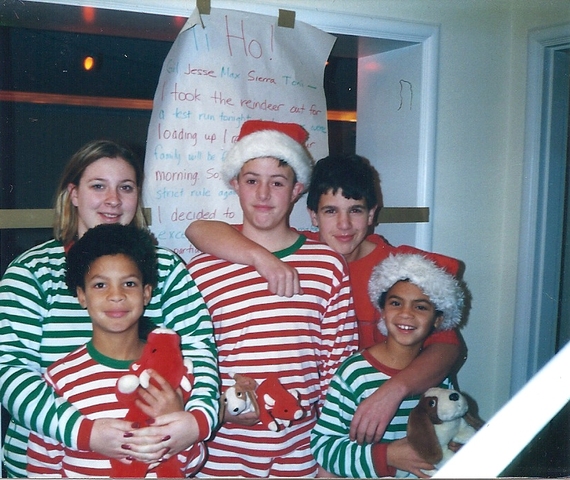

That was enough for me, at least with respect to pregnancy. I had always wanted several children, so I convinced my husband to adopt. And along the way, I learned a lot. Not merely about the process of adoption, but about other people: prospective parents and those already initiated into the "has-children" club. How many times did I hear, when having the adoption conversation, "Oh, I could never do that, bring someone else's child into my home and raise them as my own"?

That comment intrigued me then and still does. What is it that is so special about having one's own children? We've already touched on the biological imperative, but maybe there's some room for rational thinking too. I confess, it's hard not to sound judgmental, even though I too pursued the perceived goal of perfection: a live birth of a child who shared my genetic makeup. After all, I worked incredibly hard to get pregnant after my daughter died. I didn't leap to the idea of adoption. It wasn't my first choice, but it turned out to be a great one.

Let's face it: the prospect of accepting someone else's child as your own can be scary. It's a crap shoot, no question. But let's face this too: raising your own birth child is no less of a crap shoot. Children turn your life upside down, no matter where they come from, and there is no predicting their constitutions or their futures. Things never go as planned, especially over the long-term, and raising children is a long-term proposition.

When you decide to have a family, you are yielding control to outside forces. I didn't know this back in my early twenties, but when my daughter died, I discovered this unassailable truth.

My point is this: Don't toss out adoption as a viable option for your family. Pregnancy is a state that lasts forty weeks. Parenthood lasts forever. Why focus on the how of your child's arrival in your life, instead of the how you are going to do your best by her/him? From the moment your child crosses your threshold, no matter how s/he got there, it's all hands on deck to raise that being to become his or her own best self. In that process, if you let yourself, you will fall in love, guaranteed. There is nothing as conducive to loving someone as going through tough times together and coming out the other side, and if parenting doesn't provide ample opportunities for tough times, I don't know what does.

So why not take the chance to do something extraordinary? If a mere 1 percent of the population of adults struggling with infertility were to adopt a child currently in foster care, the list of 100,000 children waiting for permanent families would be decimated.

Wouldn't you like to be a member of the 1 percent?