For the past 20 years Adelina von Fürstenberg has been curating international exhibitions and screenings attended by democratic heads of state and totalitarian dictators alike. ART for the World, after all, is a non-governmental organization for the arts associated with the United Nations Department of Public Information. Founded in 1995, Art for the World began when United Nations Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali came to Fürstenberg, who was then director of the Centre d'Art Contemporain de Genéve, with the request for her to honor the founding of the United Nations with a fiftieth anniversary exhibition named, Dialogues of Peace. Since thebestn, Fürstenberg's curations have given even weight to depictions of transgendered and feminist lifestyles and views representing traditional, sometimes religious, communities opposed to them. She has produced a movie about romantic relations between a woman of color and a skinhead neo-Nazi. She advocates art that models sustainable industrial and agricultural programs presented in societies financed by fossil fuels and agricultural GMOs. She has commemorated the victims of genocide and colonization in exhibitions seen by audiences who refuse to acknowledge such deaths and oppression. All in the effort to instill dialogues of peace.

This fall, ART for the World embarks on its third decade of expanding the dialogues that Boutros-Ghali and Fürstenberg began. Whether we call them institutionalized participation or art activism, they emphasize the commitment to societies world wide on such issues as health, human rights, gender and sexual parity, environmental and social sustainability among nations, communities and individuals. When asked how she negotiates the many differences between individuals and societies, how she mediates audience response to a range of often indignant artistic expressions, she retorts, "It's megalomaniacal for artists, curators and critics to think that we 'negotiate' the terms of social and political conditions. It's impossible as cultural figures to negotiate. The most we can do is make suggestions."

Fürstenberg may or may not be right. But to hear it said hits as hard as a slap across the face. We don't have to be diplomats or politicians to fall into the pattern of feeling ourselves to be negotiating our day to day interactions, especially when we, artists and writers, act as political and social activists. But that isn't what Fürstenberg means. By interfacing regularly with the diplomats and statespeople who succeed or fail at passing referendums among 193 voting members of The United Nations, she hears the frustrations, sees the hopes that are lost, the bargaining failed, all affecting billions. Starvation, refugees, survivors of catastrophes, disease, terror, genocide: all proceed uncontrollably when negotiations stall or fail. In such voids of power how can she, can we, think that artists, critics and curators have any power of negotiation concerning what policies in the world are implemented?

Fürstenberg prefers the term 'participation' to 'negotiation'. We participate with one another to hear and to suggest what needs to be done. The language of humility is difficult for we who call ourselves activists, artists, critics, who feel we know better and must demand what is or isn't ours, or theirs, by right. But what gives us this right? Not negotiation, Fürstenberg believes, but empathy, something that is either shared or not through communication, through participation. The lesson worked for her as her early frustrations with politicians and art cognoscenti alike gave way to her winning larger and socially-engaged audiences in major cities around the world. The last year in particular has been rewarding, if solemnly, with her exhibition Armenity: Contemporary Artists from the Armenian Diaspora, which she had long hoped to curate. Installed at the Republic of Armenia Pavilion exhibition at the 56th Venice Biennale of International Art, on the Island of San Lazzaro deli Armeni, Armenity observed the centennial of the Armenian Genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Turks from 1915 to 1918. For its impassioned yet reflective engagement of intimate yet political signals, Fürstenberg was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation -- the highest honor awarded by the Biennale committee overseen that year by the the Nigerian curator and Biennale Director, Okwui Enwezor.

Fürstenberg does have convictions, and strong ones. I came to know Adelina (what I will call her when referring to our direct conversations) on 9/11/2001. She by chance was in Manhattan preparing for the premier of her touring exhibition, Playgrounds and Toys, then being installed at the United Nations' Headquarters in Manhattan with its commissioned designs to be produced by artists and installed for children in cities around the world.

In the moments after the planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon, there was concern that there might be a strike on the United Nations tower. While friends and I were calling everyone we knew who lived or worked near the Trade Center, it occurred to us that we should stop Adelina from going to the UN Headquarters. Chrysanne Stathacos, a mutual friend and an artist representing Canada and the US in the playground show, called Adelina, who then invited us to visit. As did the rest of the world, we talked, argued, accused over who was responsible for the global strife that had led to the strikes on New York and Washington.

Even on that dark day Adelina showed tremendous hope for the role that artists can play in mitigating the differences between cultures, however unrealistic or small such efforts struck others, and for however long it would take to win over governmental and financial support for causes that reflect new light and perspectives onto chronic global social issues. It struck me that day that it was difficult, even impossible, to agree with her on so optimistic a view of how art might be effective in drawing diverse regional and indigenous audiences together with audiences from the greater global art centers. I felt I knew how insular and cynical the artworld can be. Adelina, however, sees art to be a portal of humanity that cuts through even the granite-hard indifference of both the international spheres of the art market and governmental diplomacy.

I struggled with my doubts as I listened to Adelina explain the many goals for ART for the World, then just beginning its sixth year of presenting exhibitions and film screenings around the world. A week after the carnage and New York City had been declared a disaster area, security concerns forced the UN to cancel its public opening for Playgrounds and Toys but hosted a small and private unveiling of the artists' plans and some of the actual art that had been commissioned by ART for the World and which would be installed in Athens, Milan, New Delhi, London, Hobert (Tasmania), Yerevan (Armenia), and a few refugee camps in Africa. At a time that the world was debating how the United States would respond to 9/11, Adelina had been busy planning to enrich the lives of children of the world's overcrowded cities. To some it might seem a futile act of denial. For those who know Adelina, the exhibition was her light in the darkness. Playgrounds may not be an avenging army, but they were intended as proactive gestures of friendship to the children who are now in, or approaching, their twenties. How many, I wonder, look back on those playgrounds and toys as gestures of international friendship, if they even know it?

Fürstenberg (I am now returning to her public persona) is particularly invested in relaying to her audiences for art and the political models that embody ART for the World's mission of disseminating universal values in the name of Article 27 of the Charter of Human Rights. Which states: "Everyone has the right to take part freely in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts." Her delight is purposeful, given that ART for the World exists to inspire participation in humanitarian efforts and to spread empathy through art.

Fürstenberg is of course right to believe whole-heartedly in the declaration. But Article 27 may be news to too many artists around the world who have had their work destroyed, or have been imprisoned, assaulted, or worse for their expressions.

Article 27 hasn't helped Jafar Panahi and Muhamed Rasoulof, two Iranian film directors sentenced to six-year prison sentences after being convicted of "propaganda against the state". When Deepa Mehta was shooting her film Water in Varanasi some years ago, Hindu political and religious parties comprised of 2,000 protesters stormed and destroyed her film sets, burning and throwing them into the river as they burnt effigies of Mehta and threatened her life. Two of the Pussy Riot band members served sentences in a Russian prison after publicly disparaging the Russian Orthodox faith. Palestinian conceptual sculptor Abdalla Abu Rahmah was sentenced to a year in prison by an Israeli military court for "arms possession," the "arms" in question being empty gas canisters and disabled projectiles found on the ground long after they had been shot and rendered useless by the Israeli army. Juliano Mer-Khamis, an Israeli actor, filmmaker, and the founder and director of The Jenin Freedom Theater was shot five times and killed in Jenin by Palestinian terrorists. Egyptian New Media artist, Ahmed Basiony, was shot dead by the Egyptian military as he filmed video footage of the pro-democracy protests and occupation of Tahir Square. Ai Weiwei famously was apprehended by Beijing authorities reputedly for nonpayment of taxes, which he denies owing. After spending nearly two years in prison, Palestinian poet and artist Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for renouncing Islam in his book of poems, though the sentence was ultimately reduced to an eight-year prison term and 800 lashes. The Yemen National Museum has been destroyed by civil war, while Tibetan artwork has been censored by the Chinese at the Dhaka Art Summit. And the Taliban and ISIL have infamously destroyed magnificent landmarks of ancient and medieval architecture and art throughout Iraq and Syria.

We can hardly blame Fürstenberg, or even the UN General Assembly and Security Council, for the times that their charter fails us. But when it comes to the right to take part freely in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts, it will take more than "suggestions" to implement free expression. In fact, the history of art itself tells us that art has been instrumental to enabling not only oppression, but genocide and cultural erasure, a fact over which the well-meaninged humanist audiences for it can often be in denial. A brief history of activist art can enlighten us, as it has informed the founding of ART for the World. (For those who will skip the history, resume reading about Fürstenberg and ART for the World eight paragraphs down.)

Art has been used to enable not only oppression, but genocide and cultural erasure. Consider that in the last century that Wilhelm, Romanov, Hitler, Goering, Stalin, Mao, Pinochet, Pol Pot, Amin, Milosovic, Saddam, Bin-Laden, Kim Jong-il: all had been known to sit raptly at the opera or ballet, or enthusiastically attend exhibitions of fine art, only hours after supervising collective murder in gas chambers, gulags and firing squads -- or at the very moment that storm troopers or terrorists were mowing down scores of victims. It has always been well known that the patronage of much of the world's greatest art has come from generals, monarchs, emperors, caliphs, popes and dictators capable of dispensing communal death because they were bolstered by an ideology of "beautification" or "purification" of society/faith/nation/culture required cleansing. In so many cases, "aesthetics" has been imagined by the aristocratic and proletarian sociopath alike as the core inspiration and raison d'être behind such murderous visions. Aesthetics not only support but inform delusions whereby the unity of race, singularity of faith or ideology through the vehicles of pictorial, musical, literary, dramatic, poetic, athletic models of excellence. Such models of excellence reinforce the delusion that high-minded expression belongs only to the society possessed of the aesthetically superior hair/skin/mind/heart/brain/soul/ability/DNA.

History begins to change toward the end of the 18th Century and the early 19th, when the artists who redefined epochs, tastes, politics and morality saw a vitally new function for art -- one that was both ideological and pragmatic -- if at extreme times desperate. In short, art became dangerous to the murderous sociopaths in power (though art was always dangerous to the antagonists of foreign cultures, as the inspirational battle painting, and before it the battle frieze, amply evidence). Jacques Louis David's Oath of the Horatii, 1785, is widely, if debatably, interpreted to be the first apparent modern image to analogously call a nation to mobilize against its own repressive aristocracy. This interpretation persists despite that David initially supported, prospered under, then rose against, and ultimately survived the collapse of not just one, but three repressive regimes: the monarchy of Louis XVI; the revolution of Danton and Robespierre; and the imperium of Napoleon.

With David's opportunism, Francisco Goya (most famously on the merits of the painting, The Third of May, 1808, but also with the ferocious aquatint plates of the The Disasters of War in the 1810s) becomes the true great artistic exponent of democratic revolution, and afterward Eugène Delacroix, with each defining the standards to be met by any and all artists wishing to document, motivate and perpetuate dissent against militaristic and genocidal regimes seeking the ethnic cleaning and cultural erasure of millions. Goya's and Delacroix's pictorial models of documenting and advocating dissent and revolt are taken up brilliantly yet with exceeding anguish by such revolutionary pictorial painters, sculptors and photographers as Käthe Kollowitz, André Kertész, George Grosz, Otto Dix, John Heartfield, Ben Shahn, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Tina Modetti, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Paul Cadmus, Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, Alberto Giacometti, Ossip Zadkine and Dorthea Lange, to name only the most iconic Western artists.

Dada's birth during the First Great War of the 20th Century marks it as the first true ironic artistic protest movement against the first high-tech barbarism voiding European claims to ushering in the great utopian society of Modernism. Protesting explicitly against the masterpieces of art that failed to tame the savagery of the world's "civilized" nations, Dada circumvented the artist's political activism into less direct and more conceptual, ironic and anti-aesthetic, anti-programatic, and anti-ideological images, objects, acts, performances, genres and media that, a half-century later, came to be endeared by the artworld at the same time they irritated uninitiated audiences and antagonized the over-cultivated aesthetes. In the decades when independence from colonization became a catchphrase around the world, in the colonizing centers, Surrealism, with its Freudian liberation of the unconscious from religious and social taboos, and Existentialism, with its abstract conception of freedom, the expression of Camus's and Fanon's Rebels, De Beauvoir's Second Sex, and Genet's sexual and transgendered outcasts overtook Western civilization to make individual rights a basic prerequisite of human existence to be demanded by an educated popular culture in revolt. We represent, says Sartre, "freedom which chooses, but we could not choose to be free. We are doomed to freedom."

From 1945 on, artists were extrapolating the lessons of Dada as an art of passionately engaged protest. As Adorno famously cautioned that poetry after Auschwitz is obscene, artists suffered a severe existential crisis in the wake of the Holocaust, the Bomb, the Gulag, the Cultural Revolution and the myriad anti-colonial wars of liberation breaking out all over the globe. A new generation of activist artists and intellectuals sought to erase all trace of falsely-sublimated correctness or identifiable essence taking hold of middle class intellectuals fleeing both religion and political parties in their quest for freedom. In 1945, the artist's only defense was to condemn genocide with all the power that art could unleash. But that power grew with Abstract Expressionism, happenings and performance art, Guy Debord's Situationists, the Vienna Actionists, Fluxus, Carolee Schneemann's feminism, the Judson Dancers' pedestrian movement, Pop Art, Conceptual Art, Feminist, LGBT and Identity Art -- all unleashed the freedom of the individual and the democracy of the collective.

Outside the Western states that had yet to embrace democracy and capitalism, an amorphously-ideological Socialist or Marxist framework utilized Social Realist art to expand the fraught tension between classes seen to lead inevitably to revolution ― civil war hypothesized as a necessary and sacrificial progression ― regardless of how bloody or how many were slaughtered in service to the utopian ideology. With participation in all capitalist exchange deemed counter-revolutionary, depicting the "virtues" of an armed Marxist class warfare was dictated to be the ultimate course of action available to the proletariat. Ideologically informed artists from all backgrounds in the Southern and Eastern hemispheres found such notions of utopia and revolution irresistibly iconic, with the best educated and enthusiastic of party members authoring an array of artistic manifestos and programs along with highly graphic and compelling visual propaganda. Tragically, Social Realism was discredited by the 1980s, with the atrocities exposed in so many "utopian" states.

By the 1960s, the avant-garde movements were widely appreciated by educated audiences, and the youth movement that poured into art with their radical politics and predilection for cerebral concpetual art were initially neglected in much the way that the Dada and Surrealist artists had been. But thirty years later, when Boutros Boutros-Ghali came to enlist Fürstenberg to curate an exhibition of art to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations, liberal-left political art can be said to have been embraced by the Establishment, however quietly. The exhibition, Dialogues of Peace, called for artists to become passionately engaged as participants with the issues facing an emergent global civilization. Dialogues of Peace was held at the UN's Geneva headquarters as a model of participation in a new peace movement, one integrating real life with art, as if the two could ever be apart.

On the diplomatic front, Fürstenberg's multicultural (or nomadic) model of curating participates with the 193 UN Nations by bringing a diversity of ideologies represented, some that might be viewed from within to be in conflict. But such conflicts, Fürstenberg shows to be superficial when regarded in a larger global context of the group exhibition. "I am presenting art that is in defense of universal cultural values", she counters. "Agreeing on universal cultural values is the easy part of diplomacy and art. That is why the common thread of these shows, even when critical, must be uniting contemporary culture with the defense of universal values required for making peace." Fürstenberg likes to point out that the proof that universals both exist and mitigate disputes can be witnessed at the opening of her exhibitions, where in the past such opposing heads of states as Yasser Arafat and Jacques Chirac could be seen conversing with artists Alfredo Jaar, Chen Zhen and Robert Rauschenberg. The very title, ART for the World, Fürstenberg attributes to the philosopher and her mentor, Fulvio Salvadori, whose approach to art she emulates "as an approach to universality, an approach to bridging with cultures and perspectives that we can all learn from."

Fürstenberg's intentions have not always been understood and in the early years of her tenure with ART for the World, she was criticized for putting social agendas ahead of artistic concerns. When she began ART for the World, it had been only six years since the French curator, Jean Hubert Martin had assembled his controversial-yet-groundbreaking assembly of artists from every corner of the globe and representing as many ideologies and faiths, in the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, held at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle of the Parc de la Villette in Paris. Fürstenberg's global assembly of art in Dialogues of Peace, was a similar global assembly of artists. But rather than look to the past and to spiritualism and magic to establish unity, which was problematic in its experimentation for many politically-minded critics for its perceived ethnocentrisms, even condescensions, on the part of the French, Fürstenberg chose Salvadori's universality, but made it both contemporary and geopolitically urgent.

"Magiciens de la Terre did have an enormous impact on me", Fürstenberg admits. "But I organized Dialogues of Faith accordingly with its title, since from the beginning forging dialogues of peace has been the mission of the United Nations. This quest for composing dialogues of peace became the mission not only of the show, but as well for ART for the World. Since its creation, ART for the World has carried out numerous dialogues of peace around the globe, from Mexico to India, as well as the US, Brazil, Morocco, Italy, France, and of course Switzerland."

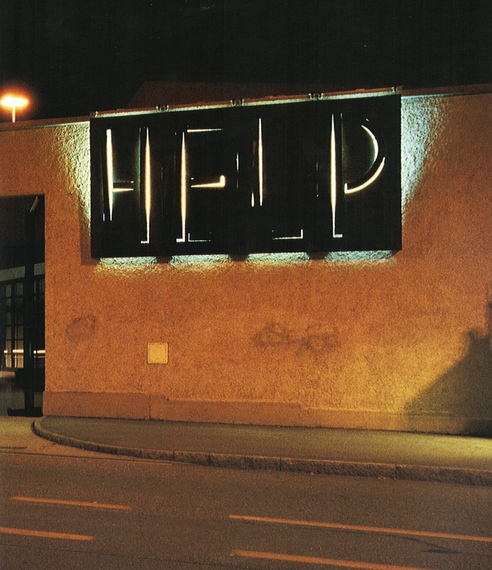

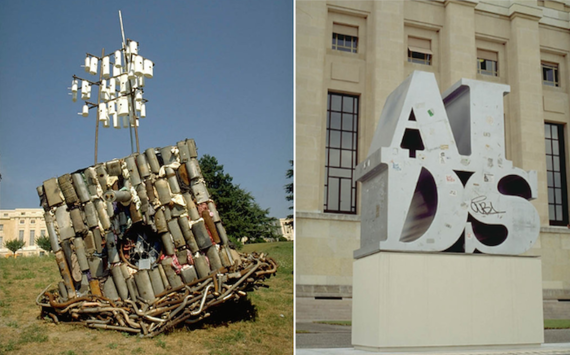

Since then there have been no less than 45 such dialogues of peace in the forms of exhibitions and screenings undertaken by ART for the World, with another seven Playgrounds and Toys installations in various cities. In 1998, Furstenberg was invited by the World Health Organization (WHO) to curate a show for its 50th anniversary. "I named the show, The Edge of Awareness and included some 50 artists from various parts of the world. I selected works that responded critically to the urgent challenges that WHO must continually confront: violence, the mortality rate, natural disasters, poverty, HIV-AIDS, chronic injustice. All the work had to be based in universal values. It could not be simply a show that only one regional sensibility would understand because, after Geneva, the exhibition travelled to Sao Paulo, Brazil; New Delhi, India; PS1, New York; and finally participated in the Milan Triennial. I didn't leave these issues just for expression and criticism through the art. On each occasion, I organized meetings or colloquiums on topics specific to the region. "

Bajo el Volcan (Under the Volcano) http://www.artfortheworldarchives.net/wwd/1996/bajo/bajo.htm

Among ART for the World's first installations, in 1996, is Bajo el Volcan, a show which indicts what is likely the world's most massive racial genocide and cultural erasure: that upon which the entire Euro-American civilization -- from Cape Columbia in the arctic north to the Diego Ramirez Islands at the southernmost tip -- is built upon. Fürstenberg responded to the appeal of three Latin American artists to help them realize their plans: Teresa Serrano and Gerardo Suter from Mexico and Miguel Angel Rios from Argentina, sought, with the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia to temporarily turn the site of Tepoztlan, the pre-Columbian temple dedicated to the god Tepoztecatl on the peaks formed from volcanic rock, into a temporary site that reunites the Mexican people with their pre-Columbian history.

The artists were intent on recalling that the Dominican order, despite being founded on the vow of Christian charity and poverty, betrayed Christ's commandment of love for one's neighbor by building their convent on the ruins of Tepoztlan and the blood of the Mexican people. In its larger context, the show was symbolic of the European religious congregations' egregious cultural erasure of Mayan society and history by building their monasteries on sites where there was already an indigenous temple. Fürstenberg would be intent on returning to the colonialist history as a departure several times over the next two decades, especially as she is interested in The Global South, comprised of Latin America, Africa and Southern Asia. Fürstenberg reminds us that although the Global South countries make up some 160 of the 193 recognized nations of the UN, with three-quarters of the world's population, they have access to only one-fifth of the world's income.

The impoverishment of the local villagers surrounding Tepoztlan was the deciding factor in Fürstenberg's commitment to Bajo el Volcan. The villagers were protesting the proposed golf course about to cover over the area, a project which required more than half a million gallons of water per day, when the villagers were still living without a modern supply and distribution of water adequate for their needs. There was also the viability of the installation acting as an antidote to cultural erasure, or what Fürstenberg proposes to be the implementation of sustainability. The region is rich with architectural styles, including the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Plateresque which must be preserved. In fact, the exhibition began ART for the World's tradition of creating contemporary art in-situ with historical architectural and natural settings to draw attention to their sustainability. There is the allure in this case of being situated so near the Aztec temple dedicated to the deity Tepoztecal. And in the end, the media interest generated by the installations helped to secure a running water supply for the village and arrested further development of the golf course. The process of cultural erasure was halted and the architectural heritage has been preserved at least for the present.

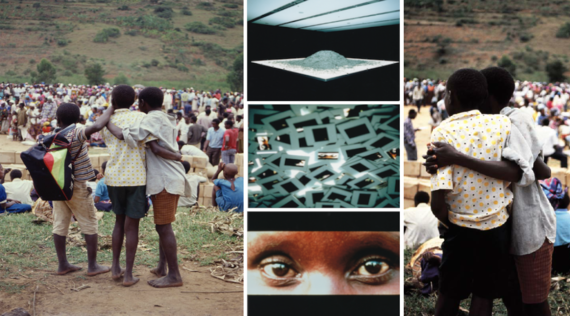

The Silence: The Rwanda Project, 1994-2000 by Alfredo Jaar http://www.artfortheworldarchives.net/wwd/2000/jaar/jaar.html

In 2001, the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar's The Silence: The Rwanda Project, 1994-2000, was installed at the International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, in Geneva. As the title designates, Jaar visually summarized the genocidal outbreak with three photographically-based works, the most moving yet ironically mundane being comprised of a mound of thousands of photographic slides, each containing the same single image: the eyes of one woman, the Rwandan Genoocide survivor, Gutete Emerita. Jaar has written:

"On Thursday morning, August 25, 1994, I entered the Rubavu Refugee Camp near Gisenyi in Rwanda, as school was about to begin. As I approached the makeshift school, children gathered around me. I smiled at them and some smiled back... When Nduwayezu arrived at Rubavu, he remained silent for four weeks. Four weeks of silence. I remember his eyes. And I will never forget his silence. The silence of Nduwayezu. Gutete Emerita, 30 years old, is standing in front of a church where four hundred Tutsi men, women, and children were systematically slaughtered by a Hutu death squad during Sunday mass. She was attending mass with her family when the massacre began. Killed with machetes in front of her eyes were her husband, Tito Kahinamura, 40, and her two sons, Muhoza, 10, and Matiragari, 7. Somehow, Gutete managed to escape with her daughter, Marie Louise Unumararunga, 12. They hid in a swamp for three weeks, coming out only at night for food. Her eyes look lost, incredulous. Her face is the face of someone who has witnessed an unbelievable tragedy and now wears it. She has returned to this place in the woods because she has nowhere else to go. When she speaks about her lost family, she gestures to corpses on the ground, rotting in the African sun. I remember her eyes. The eyes of Gutete Emerita."

Marina Abramovic: The Balkan Epics two performances at Hangar Bicocca, Milan and one at the 1997 Venice Biennale. http://www.artfortheworldarchives.net/wwd/2006/mAbramovic/mAbramovic.htm

Three essential projects by Marina Abramovic are remembered around the world for their emotionally powerful imagery and recollection of the Yugoslav wars, Milosovic's instituted policy of ethnic cleansing, and the brutal misogyny that raged throughout the region in the years that Fürstenberg was establishing ART for the World. The first performance, Balkan Baroque, was presented at the 47th Venice Biennial in 1997, for which Abramovic won the Golden Lion Award for Best Artist for symbolizing the delusion of the Serbs' "ethnic cleansing", of "Bosnia by systematically killing and expelling all Bosniaks (Muslims) in a ritual of "purification". Although Fürstenberg didn't curate it, she wrote a definitive commentary on the performance in her introduction to the book about Abramovic's subsequent work, Balkan Epic. "During Balkan Baroque, Abramovic was seated on a pile of bones that she cleaned of their remaining meat and cartilage one at a time in a purification ritual for herself and the massacres taking place in the Balkans. In short, she added a dimension of human warmth to her work, though this did not replace the earlier themes of experimentation and physical resistance: on the contrary, in some way it threw new light onto her past works. The pain of her return to a homeland torn to pieces by war was perhaps more difficult to support than the purely physical pain she suffered in her early performances."

Balkan Epic, performed at Hangar Bicocca, Milan, has been keenly observed and commented on in the ART for the World book by Furstenberg. The book counts among the most insightful and passionately-engaged writing on Abramovic's art. With a body of work conceived and executed from 1997 to 2005, the exhibition and book adds an extensive range of psychologically-artistic virtuosity to Abramovic's conceptualism, a range that, as Fürstenberg claims in her introduction, "confront us with the gaps between hope and total destruction, with heroism, idealistic passion, human warmth, and almost unbearable static situations ... [in which] Abramovic creates new, surprising perspectives on archaic rituals that used erotic powers to influence fate and fortune. Such powerful images talk to us about the disavowal of ancient practices, and about something buried deep in our consciousness. That something is of course our innate resistance to being forgotten, from being made irrelevant, for being broken from our lineage."

Fürstenberg relays that Balkan Epic conveys how deeply the conflict in the Balkans disturbed and altered Abramovic. The war and its atrocities compelled the artist to look back to her Serbian and Montenegrin heritage that she had neglected in the years that she worked as an international artist concerned with conceptual performance art. "Marina had never before made war and death the themes of her art. There was also the death of her father, the war hero who had fought for Tito's Yugoslavia during the Second World War that added to the anguish of seeing the Balkans torn apart by war. Before this she suffered physical pain in her performances," Fürstenberg states. "But now the torment was psychological as well."

Perhaps the most socially significant aspect of Balkan Epic is Abramovics' photographic and cinematic portrayal of women whose protections have deteriorated. We in particular view the isolation and devaluation of women in society. Abramovic came to see that the crimes perpetrated on the Serb, Croat, Montenegrin, and Muslim populations, when each had become minorities in the newly fashioned nations from the ruin of Yugoslavia. Each also had a distinct gender-specificity: men on all sides of the conflict were taken from their homes to be killed while women were spared death in exchange for their rape and torture. Abramovic's search for the origins of the deterioration of Balkan morality appear to have coincided with a loss of reverence for sexuality that had survived the centuries prior to modernization. As her sense of the history of the Balkan peoples heightened, Abramovic was impelled to make what was for her, a new kind of art in which the differentiation of sex and gender shows itself to both generate and be generated by deep-seated belief and ritual systems that somehow survive a life under siege.

The Language of Equilibrium by Joseph Kosuth, Island of San Lazzaro deli Armeni, Venice Biennale, 2007 http://www.artfortheworldarchives.net/wwd/2007/kosuth/index.htm

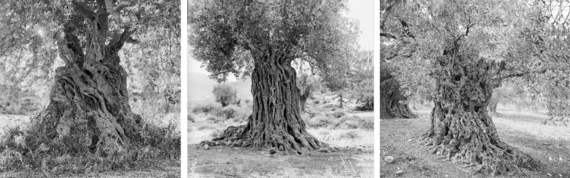

Eight years before Fürstenberg curated Armenity on the Island of San Lazzaro deli Armeni, at the 2015 Venice Biennale, San Lazzaro was the site that she and the artist Joseph Kosuth chose for the 2007 Venice Biennale's presentation of Kosuth's visually spectacular, The Language of Equilibrium. Installed on the external walls of the Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order, this time diaspora culture, not the genocide, was the topic. Kosuth used a vibrant yellow neon text mounted on the facade of San Lazzaro and ran it along the perimeter wall, spanning approximately 150 meters over the observatory, the promontory and the bell tower of the Monastery encircling the island. The texts are affirmations of Armenian existence relayed by their surviving language and writings. Fiona Biggiero explains that, "'The Language of Equilibrium' uses the linguistic definition of 'water' ... water is seen as a primary element and refers both to the water surrounding the island and it's defining historical role in Venice, as well as the importance of water in the global discourse on the environment today. The work could be seen while crossing, the Venetian Lagoon."

Here Africa (Ici L'Afrique), Château de Penthes, Geneva, and, AquiAfricaSESC Belenzhino, São Paulo, http://www.artfortheworld.net/here-africa

Two exhibitions the world should know more about for representing the art of a continent poorly represented before the rest of the world, is the 2014 selection of African Art that Fürstenberg assembles with Here Africa (Ici L'Afrique) and in 2015, AquiAfrica.

In Here Africa, ART for the World presented sixty works by 26 African artists. Although the work is not always about diaspora culture or referential to the long shadow of the former slave trade and colonization, the exhibition grapples with issues generated by economic impoverishment or emanate from nationalist and tribal political struggles, aspirations for success, as well as healthy self-effacement over common fantasies of acquiring wealth, power and prestige the educational and economic systems that once informed their culture and power as societies and nations. No doubt because African artists have not been finding sufficient inroads into the global markets that so far are still formidably resistant to their political and cultural aspirations, Fürstenberg curated a second exhibition of African Art, AquiAfrica, just a year later. This time the artists of African-descent hail from the islands of the Carribean and the American mainland whose art is rightfully a reflection of all those in the African workforce who struggle over centuries of European, Asian, and American dominance, and the cultural hybridizations via the global media that displace traditional values, aesthtics and traditions, and of the imposed colonial cultures. Fürstenberg enumerated their artistic and political concerns as being their "roots, the dark period of the slavery, and the problems endemic to "immigration, climate change, water and food, health, issues of human rights, education and gender equality."

In her introduction to the accompanying book, Fürstenberg writes that she has selected work that refers to the "extreme urgency, struck by the physical and psychological violence of slavery" and the "survival space in its culture and in particular in musical expression". There is special interest in the new African art that raises questions of identity. "If traditional art remains strongly grounded into the African world and being, the new art develops in favor of shared social identity. African contemporary artists take their inspiration from the continent's traditions, as much as from the contemporary urban realities of a mutating Africa. They bring together Western cultures and Africa, while raising the profound political question of where Africa is going. These artists develop an art dealing with issues of both identity and identification; for them the question of artistic identity is that of their own African identity."

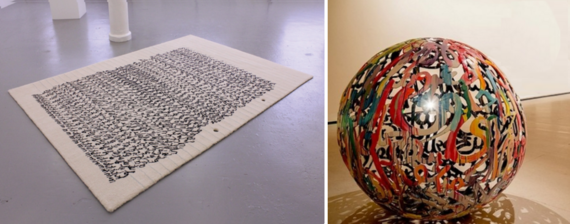

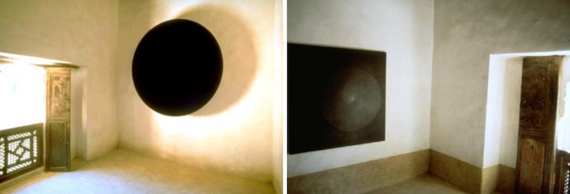

Meditations, Marrakech, Morocco, 1997 http://www.artfortheworldarchives.net/wwd/1997/med/med.htm

This little-known show of painting and sculpture has much to tell us about the evolution and true inventions of visual abstraction around the world centuries before modern art appeared in the 20th century. Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian and Klee all acknowledged these earlier abstractions in what little they learned about non-Western spiritual visual systems, and now it seems before them by the artist Hilma af Klint. Abstraction comes to modernism at least in the West by route of inheritance from Pythagorean and Vedic metaphysical and spiritual values. (Traditional societies in all other parts of the world likely knew what we call abstraction or ornament indigenously or by trading.) The artists, Marco Bagnoli, Alighiero e Boetti, Farid Belkahia, Joe Ben, Silvie Defraoui, El Sy, Shirazeh Houshiary, Ilya Kabakov, Kacimi, Anish Kapoor, Rachid Koraichi, Sol LeWitt, Andrea Marescalchi, Maria Carmen Perlingeiro, Miguel Angel Rios, Sarkis, Pat Steir, Chen Zhen, are all situated within a school formerly devoted to the study of The Qur'an. Pythagorean formulations made possible the development of the abstract Islamic ornament that flowered among sophisticated medieval Arab, Persian and Indian designs where figurative representationvwas prohibited.

The solemn, quiet abstractions of Shirazeh Houshiary and Anish Kapoor, besides being conducive to meditation, reflection, even prayer, embody certain of the principles of Islamic ornament and Tantric mediation practices that utilized highly sophisticated systems of abstraction not unrelated to the kind of meditations that for six centuries filled these very chambers in the Médersa Ibn Youssef. Fürstenberg has gone on record stating that the spiritual in art is a fundamental of the human condition and we must learn to deal with it. "I think artists have dealt with it. I am not so sure that those who write about art have been able to deal with it. It requires, I think, on some levels a great deal of intelligence and humility." What the Merdersa encourages.

Armenity, 56th Venice Biennale, 2015 http://www.artfortheworld.net/armenity

Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg only began to professionally cite her Armenian birth name, Cüberyan, in 2015. In conjoining it with her betrothal name, she became intent on showing her solidarity with the murdered and diaspora Armenians she was honoring. In her introducion to the exhibition, Fürstenberg not only wrote about Armenia and Armenians, she wrote about the source of her own universalist vision when she notes, "the last one hundred years, despite the Medz Yeghern, an expression that Armenians use to denote the period of massacres and deportations that peaked in 1915, Armenian culture has survived and artists of Armenian origin have remained genuine citizens of the world-at-large: on the one hand deeply attached to their roots and aware of their own historical individuality, but also able to create productive connections with the culture of their country of adoption."

"I was inspired by the French word Arménité to call the show Armenity. It seemed to me an appropriate new word to describe a new generation of artists and intellectuals in constant flux, which nevertheless kept a subjective sense of being-in-the world. Armenity questions the concept of Armenian identity as being the result of the historical connections characterizing Armenian culture through the millennia from the lands of Anatolia, the Caucasus and throughout the diaspora since its inception. The richness of the exhibition finds expression in the diversity of creative ideas and narration and the vision of each of the artists and intellectuals involved. It is a direct reflection of a continuous process of preservation and enrichment that has allowed the Armenian culture to be integrated but not assimilated in even the most adverse conditions. "

Armenity brought together 18 artists from different generations, many living in different nations, "under the banner of a dispersed identity", art by such leading contemporary Armenian artists as Sarkis, Gianikian-Ricci Lucchi, Anna Boghiguian, Nina Katchadourian, and Rosana Palazyan formed a collective vision of diaspora culture. Which is why Adelina surprised me when, in planning this post, she told me she didn't want to be remembered as a curator of shows about genocide. Yet activists and scholars on genocidal history remind us that historical amnesia and denial of past atrocities among governments and populations is ubiquitous as a result of institutionalized amnesia -- the final goal of the power that impelled the genocide being complete cultural erasure. Once memory of genocide is deeply buried, the cycle of repression, dehumanization, persecution, and ultimately the execution of whole populations seems feasible. Art MUST remind us of the history of genocide to prevent future atrocities.

With Armenity now her legacy, Fürstenberg is psychologically enabled to motivate others to engage constructive participation. Participation is a philosophy she learned from Joseph Beuys, a controversial artist she greatly admires."Beuys was a pivotal influence: 'I immediately subscribed to his belief in the creative capacity of every individual to shape society through participation in cultural, political, and economic life, and in the production of art and knowledge through viewer and artist." Hence, her recent publication, Participation, celebrating 20 years of ART for the World is being released this month to, in her words, "motivate people, draw them in to contribute to solutions and their implementation."

Fürstenberg considers Armenity to be her last Venice Biennial curation after having participated in various capacities in seven. Given that she returned to the Island of San Lazzaro deli Armeni (see Joseph Kosuth, above), the historic diaspora territory the Venetians shared with the fleeing Armenians, it is no surprise she attained her most passionately engaged commitment to art activism in commemorating the centennial of the most murderous and far-reaching of the three genocides perpetrated against the Armenian people by the Ottoman Turks, that spanning 1915 to 1917.

The exhibition and its award are much more than the crowning achievements of Fürstenberg's career, given that as the director and chief curator who has consistently challenged the artworld's neglect of politically charged-yet-urgent topics. Armenity is an affirmation of a career devoted not only to expanding the parameters and showcases of significant contemporary art in ways instrumental to the implementation of social change. It is also a symbolic recognition of Fürstenberg's commitment as an ambassador in the advancement of cross-cultural exchange and assimilation as vehicles of unilateral efforts in the mitigation of international conflicts and atrocities through ART for the World.

Stories on Human Rights and Histories from Another World film screenings and presentation of the book Participation http://www.artfortheworld.net/stories-on-human-rights

On 10 December 2008, the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ART for the World screened a film comprised of short films by twenty-two artists, writers and filmmakers from around the world called Stories on Human Rights. (See the video trailer at the top of this post or the website.) On 30 September 2016, Stories on Human Rights was screened along with a new selection of films, Histories from Another World at the Cinema Trevi, Rome. Together the films summarize the issues that unify the ART for the World mission promoting development, dignity, justice and participation for all people. The 2008 screening was consecutively shown in cities around the world, in New York during a special session of the United Nations' General Assembly and in Paris at the Palais de Chaillot, where the Declaration was signed in 1948.

AQUA, Berges de Vessy, Ile Rousseau, and Chateau de Penthes, Geneva, 22 March to August 2017 http://www.artfortheworld.net/the-elephant-knows-how-to-find-waterhttp://www.artfortheworld.net/aqua

AQUA is a sweeping contemporary art exhibition now in preparation in Geneva, in venues close to Lac Leman, the Rhone and Arve Rivers, and the park and Chateau de Penthes. Composed of paintings, sculptures, installations, videos, photographs and performances of numerous internationally renowned artists. AQUA's aim is to bring public awareness to the issues on the preservation of our environment and sustainability, in particular to issues linked to water and the impact of human activity on the equilibrium of our ecosystems.

With AQUA, Fürstenberg is now turning her attention to the environmental impacts of the shortages facing populations, beginning with Syria and Lebanon. She is particularly passionate about artists who are working with water. Upon contacting her this week, she couldn't contain her enthusiasm.

"In the context of my current art project, Aqua/Water, opening in Geneva on March 22, 2017, which is World Water Day, I'm preparing with Nigol Bezjian, an Armenian-Syrian filmmaker who was born in Aleppo where he studied and lived with his family until he moved to Beirut to produce a movie investigating questions surrounding the drinking water in Syria and in the Lebanon refugee camps, among others. We rarely hear about the difficult situations developing in refugee living conditions: what happens to the drinking water in the war zones, especially in the destroyed urban areas, where civil society is so severely afflicted by violence. What happens here to our basic right to drink water? Do we have any idea of the extent to the pain and suffering of this population with their daily search for water?"

"Besides this specific question of drinking water, for those trapped in the war zones and having to contend with the long queues of refugees, to quote Ismail Seralgeldin, Director of the Library of Alexandria, 'If the 20th-century wars were fought over oil, the 21st-century wars will have water as their main object of struggle.' People living in the West don't yet have an awareness of the severity of the shortage. Which is why I intend to make water a central issue of the exhibitions I will be curating for ART for the World".

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.