Epic and sweeping, a new book from the University of Chicago Press chronicles the work of three artists from that city whose courageous work intertwined from the late 19th century to the middle of the 20th.

Each soared to the height of his profession, and each met a tragic end.

For a prolific 15-year period between 1880 and 1895, Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan teamed up to produce an architecture that was stridently American -- one that simultaneously drew from nature for its ornament, while creating simple, modern forms on steel frame walls.

Now the Richard Nickel Committee in Chicago, named for the mid-20th century photographer who documented the two architects' work, has published a book of their designs - one that's as all-encompassing as any aficionado could want.

"It's overwhelming," said Ward Miller, director of the committee. "It's one surprise after another. It contains the complete works -- all the buildings, all the projects, and a catalogue raisonne in the back 108 pages of the book."

Much of the credit for that goes to John Vinci, author of six of the book's chapter essays, and the acknowledged force behind getting this 50-year project completed.

It was designed by Bruce Baker in a format twelve inches square, with 815 photos, many of them nearly full-bleed, lavishly spread across 461 pages. It begins in 1879 with Adler's Central Music Hall Block in Chicago, and ends in 1900 with Sullivan's bank for Enid, Oklahoma, now demolished. In between are color and black and white photos of buildings that range from inspirational in their design to demoralizing in their degradation.

"Great architecture has only two natural enemies:" photographer Richard Nickel once wrote. "Water and stupid men."

He was in a position to know. From 1952 until 1972, he devoted his life first to photographing the work of Adler & Sullivan in Chicago, then to salvaging artifacts when the firm's buildings faced the wrecking ball, and finally to saving what few structures he could.

It was a decidedly uphill battle. Of the 256 buildings designed together and separately by Adler and Sullivan, only 30 remain standing across the nation today. Most of Chicago's stock was lost in the 1960s and '70s.

Chicago columnist Mike Royko once wrote of Nickel, "I figure that anyone who tries to save landmarks in Chicago is goofy enough to teach celibacy in a Playboy Club or nonviolence to Dick Butkus."

But try he did.

Nickel got started in 1952 as a student in photographer Aaron Siskind's class at the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Together in 1954 they mounted an exhibit on the architecture of Louis Sullivan, and then embarked on a book project that has finally evolved into "The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan" today.

His master's thesis was a continuation of the Sullivan project in which the photographer discovered and documented 38 previously unknown commissions by the firm.

"He wanted to show the structures in their context," Miller said. "Some were in dire straits. Some were remodeled. Some were beyond recognition. But still, you can see the intense detail -- the master's capabilities in the best qualities of these buildings. It's Nickel's focused views that reveal the genius of Louis Sullivan."

The book's first 323 pages are filled with photos taken by Nickel in the 1960s and '70s, as he sought to catalog the declining state of the firm's work. Also included are contemporary color photographs of Adler & Sullivan's 30 remaining buildings.

"The book is a reference and a research tool," Miller said. "It's already working very hard -- it was very useful in earning the Isaiah Synagogue, pictured on page 204-205, with an essay on page 439, its Chicago Landmark designation."

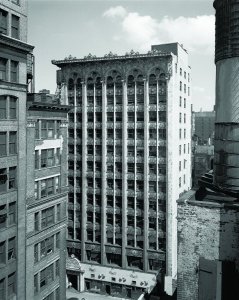

Of particular interest is the soaring, 17-story, mixed-use Schiller building, with its 4,500-seat auditorium, first-class hotel, and offices -- including the 16th floor for Adler & Sullivan themselves.

There are also the still-standing Auditorium Building, the restrained and remarkably modern Albert W. Sullivan residence, the Schlesinger & Mayer Store (now Carson Pirie) and a particularly thorough treatment of all of Sullivan's jewel-box banks across the Midwest. Then there is the Chicago Stock Exchange, painstakingly photographed by Nickel during its demolition.

The firm split up in 1895 after a severe economic downturn. Adler left to work for the Crane Elevator Company as chief salesman, but returned to Chicago after six months. A dispute over architectural credit for the Guaranty Building in Buffalo further separated the pair. And though they each worked on the Schlesinger & Mayer Store by necessity, there's no documentation of their relationship.

Adler died of a stroke in 1900. Sullivan would live until April 14, 1924, when he succumbed to heart failure, alone and penniless in a room in the Warner Hotel on Chicago's South Side.

In 1972, Richard Nickel's work came to its own tragic end. While he was inside the Chicago Stock Exchange, its demolition underway, the floor collapsed. His body was found 28 days later on a lower level, perfectly preserved and encased in plaster dust.

"He'd salvaged the staircase for the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the trading floor for the Art Institute of Chicago," Miller said. "On that day, he was salvaging a stringer from the staircase."

He was killed on April 14, 1972 -- 46 years to the day after Louis Sullivan's passing.

To order a copy of the book, go to the University of Chicago Press, the Richard Nickel Committee, or call 773.528.1300.

For more by J. Michael Welton, go to http://architectsandartisans.com/