What would a work as rich and lustrous as Edwaard Liang's Age of Innocence look like if you could see it, unlit and unformed, before any of it had been made? What would it feel like, what would it be like, to see the unilluminated beginnings of something whose ending was a bright, compelling, complex success?

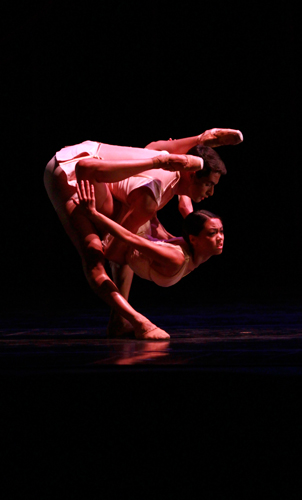

The Joffrey Ballet performing Age of Innocence. Photo by Herbert Migdoll

The Joffrey Ballet performing Age of Innocence. Photo by Herbert Migdoll

When the Joffrey Ballet performs Liang's Age of Innocence in its Spring Desire series this month, their audience will see the return of a powerful and profound work, presented with all of the richly-woven precision that the Company is known for. What would it look like, though, if you could see it begin, before it was anything but a vision?

"Vision" is a misleading, paradoxical word when it refers to the beginnings of creativity. It describes an ability to perceive what cannot be seen, because it doesn't yet exist. It implies that you can model a wholly intangible idea, by layering small strips of newly mixed reality on top of it like paper mache, until it finally becomes something undeniably real. Is it possible to glimpse the chimerical beginnings of something as multilayered as Age of Innocence? Maybe, but the only imaginable way would be to track the making of the work in reverse, beginning at the end.

The end is where the Joffrey dancers light up every part of every packed house, as Liang paints a stage full of private, personal portraits in the muted colors of quietly intricate movement. Most of his subjects move in crowded scenes, set to carefully matched music from Phillip Glass and Thomas Newman, except when the work's two pas de deux show achingly contrasted pictures of breathless hope, and of hopeless longing. Set in a bygone world where choice in love is limited to a few precious moments, where happiness can sometimes only be borrowed for as long as the next dance can last, Age of Innocence transcends its historical setting at almost every turn. By classical standards the movement is sinfully graceful, and the costume design by Maria Pinto, like the movement and the music, conveys a barely conscious conflict between restrictive formality and the secret confessions of unspoken dreams.

So how in the world did Edwaard Liang ever find all of this? If you wanted to know that, you would have to somehow track the progress of his exceptional insight; you would have to work your way back through the inspired way that Edwaard Liang makes Dance.

Jeraldine Mendoza & Mauro VillanuevaPhoto by Herbert Migdoll

Jeraldine Mendoza & Mauro VillanuevaPhoto by Herbert Migdoll

"I'm only one component in this" is the very first thing he says, describing Age of Innocence as he finishes rehearsal at the Joffrey. He goes on to talk about the dancers, the costumes, the lighting, the administration -- about all of the people who make it possible to make a work like this. It's not difficult to understand what he means, coming straight from the relentless display of focus that is a Joffrey rehearsal. The full cast is there, continuously attentive to Liang's direction, spread out around the perimeter, or moving across the floor of their brightly expansive rehearsal space. Preparation and precision are in motion everywhere, as everybody who isn't involved in the section being rehearsed works separately on something, anything, that they might want to be flawless at later. It's a memorable showing of how much goes into making a work like Age of Innocence, but it's nowhere near the beginning of the story.

Liang offers an idea of where this beginning may end though. "I really believe that music comes first," he says unequivocally, and the music for Age of Innocence is an important part of its story. This is the first work where Liang has combined the music of different composers, and the soundtrack was carefully constructed, with the second and fourth movements from Phillip Glass' Symphony No. 3, along with the same composer's "The Poet Acts," leading into Thomas Newmans "Little Children (End Title)." Hearing the full score in performance, or repeated extracts at rehearsal, the music captures everything driving and dynamic in Liang's vision, but still implies a quiet, brooding melancholy.

That's not an accident. Long before anybody sees anything that Edwaard Liang will make, he immerses himself in the music that he will use, doing so with a passion and attention to detail that nobody could suspect. He says simply, "That's all I do, I search for music and I search through music." He found Thomas Newman's "Little Children (End Title)" first; it's the score for the ending of Age of Innocence, but it was only the beginning of a demanding process. The importance of a successful soundtrack, one that will flow through his entire work, is paramount to Liang. He listens and studies incessantly, and to find the precise musical impact he needs, he works with composer Justine Chen to analyze and understand every musical parameter of what he's choosing. Together, they go over the entire score to make sure that all of the selections work together musically, examining details as subtle as the way the strings are bowed in each work.

When he has his final score, he lives in it. "Once I have the playlist, I listen to it a thousand times," he says, going on to explain why: "The music will tell me exactly what the steps are." He listens whenever he can, wherever he can, in airports and hotel rooms, shopping, walking, cooking, everywhere. "Music comes first," Liang insists, and this might even be understatement, because his appreciation of its importance to what he makes is so clear and so profound. It may also be one step past the real beginning of the story though, because before Edwaard Liang finds any music, he's already begun to find something.

Fabrice Calmels & Victoria JaianiPhoto by Herbert Migdoll

Fabrice Calmels & Victoria JaianiPhoto by Herbert Migdoll

As he explains his observation about being "only one component" in a work like this, it becomes more and more clear how important that understanding is to him; he is vividly conscious of the ways that many, many people work together to make something as intricate as Age of Innocence. It's a practical insight, and in its appreciation of other individuals, it's also a personal insight. In a sense it's the beginning of how Edwaard Liang makes anything, but it's not the entire story of the beginning of Age of Innocence.

"I had been studying and reading a lot about energy and about quantum physics," he recalls. As he listened to Newman's piece over and over, "the music triggered in me thoughts of all of the books I had read by Jane Austen." Imagining a ballroom long ago, full of expectation and uncertainty, where no one had any more than a few moments and a few whispers to find love, Liang began to reflect on what it would be like to live that way, with only those kinds of choices. He wondered if there would be some trace of those feelings, of those lives, in some energy still present in the places they lived, that would tell us how it felt to live lifetimes of hope, often disappointed, in a few passing, formal moments. "I began to wonder, what stories were left in those walls," he says, "what would they whisper to me?"

Age of Innocence began with Liang's exploration and insight into how it would feel to live as people lived, and in many places still live, without choice, to try to understand what it would be like if that were the only life you knew. Yet in another way, the making of Age of Innocence involves an even more careful, studied awareness, an understanding of how it feels, what it's like, what it takes to work with others to make something masterful. Liang's insight is at its root the result of a willingness to understand, and the many shades and colors of that willingness, of that understanding, are what eventually became the luminous success that is now Age of Innocence.

From the very beginning, that was Edwaard Liang's vision.

This article originally appeared at 4dancers.org.