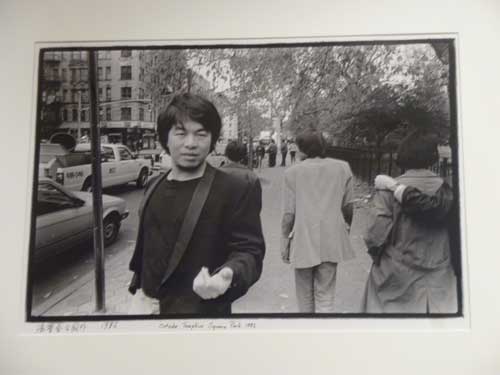

Ai Weiwei's self-portrait, "Outside Tompkins Square Park," 1986

Photo by Lee Rosenbaum, from Asia Society's current installation

It didn't take long for Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, released from detention on June (but not entirely free), to resume his provocative ways, placing himself in possible jeopardy.

My advice to you is this: Hurry over to Ai Weiwei's Google Plus page (established on Monday) while you still can. Who knows how this latest (and, given his recent 81-day detention, most audacious) thumb-in-the-eye to the Chinese authorities can remain online and uncensored?

As Jeremy Page of the Wall Street Journal reported at the time of Ai's release last month, the dissident artist was barred from speaking to the media, "including through Twitter," for at least one year. He seems to believe he has found a loophole (for now) in Google Plus, the new rival to Twitter and Facebook.

Or maybe not: Page wrote, further down in his piece, that Ai "also confirmed that the ban applied to social media such as Twitter" [emphasis added].

In any event, it seems clear that the time Ai spent in forced contemplation of his alleged crimes did nothing to repress his spirit of political resistance. Along with his two innocuous inaugural comments on Google Plus ("I'm here, greetings," and "Here's proof of life"), he also posted some colorful give-'em-the-finger images of traditionally garbed Chinese warriors, in the tradition of some of his best-known photos, where he gives the finger to such landmarks as the Eiffel Tower, the White House and Tiananmen Square.

Much of Ai's recent work has focused on documentation of governmental malfeasance or abdication of responsibility. His new site personalizes that practice, posting documents related to his own situation. This document, in the Buzz section, relates to the Chinese government's tax delinquency charges against him.

Signed by Ai's wife, Lu Qing, it mentions going to a police station to view accounting information and also refers to lodging a "strong protest" related to the authorities' alleged refusal to provide accounting information and their alleged denial of the defense's "right to cross-examination."

According to Andrew Jacobs' New York Times report, published soon after Ai's release, the artist "is facing almost $2 million in fines and unpaid taxes."

One of Ai's posted photo albums contains 249 images chronicling, in minute detail, the demolition by the authorities of his Shanghai studio last January.

Contingent on his being allowed to leave China, Ai has accepted a teaching offer at the Berlin University of the Arts. The terms of his release, however, restrict him to Beijing for one year.

Although he is not allowed to talk to the media, Ai did manage to say this recently to the Guardian:

My art will never change. It is deep in my bones. But it has made many things clearer. I have been working in the direction of freedom of expression. I think that is most important for my art.

It seems, then, that Ai is determined to disprove the title of my CultureGrrl blog report (linked at the top of this post) about the end of his detention -- Ai Weiwei Is Released (but his freedom of expression isn't). He is already testing the boundaries of what he can get away with. It's troubling, astonishing and admirable that he still has the courage to spar openly with the authorities on whom his continued (although circumscribed) liberty depends.

Speaking of which, there's currently a show of Ai Weiwei New York Photographs: 1983-1993 (to Aug. 14) at the Asia Society Museum in New York (planned in cooperation with the artist, long before his detention complicated matters). In a preview walkthrough for the museum's staff of his chronologically arranged images (mostly of documentary, rather than artistic, interest, from his formative years spent in the city amidst a community of soon-to-be famous young Chinese artists), museum director Melissa Chiu said this about Ai's photos of the 1988 Tompkins Square protests:

It became well known that there were examples of police brutality at some of these protests. A lot of people have surmised that this was a time when Ai Weiwei would have started to see the power of individual voices and how individual voices can actually make a difference, through those protests that he saw.

I was allowed to tag along during the staff's walkthrough with Chiu. Here's my CultureGrrl Video of some excerpts: