Merry pranksters Ben Hecht & Charlie MacArthur set off a fireworks display on August 14, 1928 at the Times Square Theatre on 42nd Street. The laughter is still crackerjack eighty-eight-eight years later, as the pair's first collaboration--The Front Page--opens October 20 at the Broadhurst. Broadway had by 1928 seen a handful of dynamic plays which brought real-life characters, gritty situations and brutally frank language to the stage. Hecht & MacArthur's melodramatic comedy combined them all in a deliciously entertaining depiction of a big city newsroom, which remains as viable today as it was nearly a century back.

The collaborators were rough-hewn, anything-for-a-story ex-newsmen from toddlin' Chicago. They were not all that similar, though. Hecht (1894-1964) was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the son of Jewish-Russian immigrants. He was rough and tumble and smart, and would become perhaps the most successful screenwriter of his time. MacArthur (1895-1956) was the son of an American evangelist, from Scranton. He was just as quick and smart as Hecht, but he was also lovable; everybody's favorite, apparently, with lackadaisical drive but ever-abundant charm. (He is not the MacArthur of the MacArthur Foundation and those 'genius" grants; that was his younger brother, John T. MacArthur.)

Both were exiles from the press room, Hecht from the Chicago Daily News and MacArthur from the Chicago Tribune. Both headed to New York in the early 1920s, angling for success on the stage. Hecht, by this point, was already a noted novelist; he also wrote the screenplay for the silent "Underworld," for which he would receive the Best Writing Oscar at the first Academy Awards. After not-quite successful collaborations with others, they paired up determined to write a hit. (Hecht's 1927 play Man-Eating Tiger, which preceded The Front Page with a journalist in a central role, had folded during its tryout.)

The new play is built around a ragtag group of reporters in the press room at the Cook County Criminal Courts Building in Chicago, awaiting an execution at daybreak so that they could file their stories. Ace reporter Hildy Johnson--who has quit to move to New York with his soon-to-be wife--stops by the press room to say farewell to the boys; editor Walter Burns, though, is bound and determined to keep Hildy chained to the Herald-Examiner.

Burns was based on the famously blustery Walter Howey, MacArthur's editor at the Tribune; Johnson was based on a daredevil reporter named, indeed, Hilding Johnson. (A criminal court reporter for the Herald-Examiner who died in 1931, he used to call The Front Page "that play those guys wrote about me.") The playwrights' success in drawing a stageful of flavorful reporters was not simply fanciful; the motley crew was based on real Chicago reporters, using actual names including Buddy McCue of the City News Bureau and Jack Schwartz of the Daily News. The prissy Bensinger was based on a real reporter, too, although the name was changed to protect the innocent.

Despite the financial bonanza of The Front Page, none of the progenitors bothered to pursue a slice of the proceeds. (How times have changed.) In fact, when the touring company of The Front Page hit Chicago, many of the 'original' reporters were in the house for the raucous opening night, yelling and cheering the characters (and themselves). One of them went so far as to tell the authors that they should have made the play "more personal."

The script was finished between bouts of drinking, after which Hecht & MacArthur got it to Broadway's most famous producer of the day; or, actually, of the past year. Ex-press agent Jed Harris (1900-79) was anointed an instant genius when he produced the landmark melodrama Broadway in September 1926, and then astounded the street by producing two more, major hits--Coquette and The Royal Family--within a seven-week period in the fall of 1927. The first two had been directed and co-authored by a remarkable new playmaker, George Abbott; but Harris saw fit to cheat Abbott out of promised director royalties, instantly alienating him for life.

Harris, meanwhile, was so impressed with George S. Kaufman--who wrote The Royal Family in collaboration with Edna Ferber--that he immediately decreed that Kaufman should become a director, pressuring him to stage his next offering. The Front Page came to Harris in a familial way. The Abbott-written Coquette, starring Helen Hayes, had just opened. Charles MacArthur was boyfriend to Hayes; they wanted to get married, but were foiled by vehement objections from Helen's battle-axe of a stage mother. (Charlie had his revenge by writing a highly unflattering portrait of his future mother-in-law into The Front Page; Hayes herself eventually played the role--her own mother--in the 1969 Broadway revival.)

The Front Page opened its tryout on May 14 in Atlantic City, to great success. One role was excised: that of a Chicago alderman named Willoughby, played by Charles Gilpin (who in 1920 had given a legendary performance as the title character in Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones). After a short period of great acclaim--including being honored at President Harding's White House--Gilpin had become a severe alcoholic. At the dress rehearsal, he entered and immediately froze, stone drunk. Rather than publicly fire and replace him, Kaufman and the authors simply cut the one black character out of the play. (The character being executed has been convicted of killing a black policeman, stirring up trouble in the alderman's ward.)

As was the practice in those days, the play closed down after the tryout week and reconvened in late July to rehearse the rewrites and prepare for the Broadway opening. The Front Page was an instantaneous smash. "By superimposing a breathless melodrama upon a good newspaper play," said Brooks Atkinson in the New York Times, the authors and director "have packed an evening with loud, rapid, coarse and unfailing entertainment." While Atkinson called it "a racy story with all the tang of front-page journalism," Times owner and publisher Adolph Ochs was shocked by the play--which called a reporter "a cross between a bellboy and a whore," and went so far as to sneer at the Times--as an attack on the newspaper business, and threatened to reject advertising. (It should be noted that the drama editor of the Times at the time was no other than Kaufman himself, who held onto his day job until he was convinced that he could make a living on Broadway.)

As for the lovers, Harris canceled the performance of Coquette on opening night of The Front Page so Hayes could attend. After reading the rave reviews in the morning papers, Hayes and MacArthur rushed down to City Hall and got married. And Helen, of course, was back onstage that night in Coquette.

With Coquette, Royal Family and The Front Page selling out and five companies of Broadway cleaning up on the road, the "boy genius" producer flung a vile insult at Kaufman, instantly alienating him for life. (When someone remarked that Harris was his own worst enemy, Kaufman famously replied: "Not while I'm around." And years later, when Kaufman feuded with the producers of Guys and Dolls--which he directed--he called Feuer & Martin "Jed Harris rolled into one.")

Abbott and Kaufman (separately) became the premiere Broadway playmakers of the twentieth century. Harris remained active until 1956 but never came close to equaling his four Abbott/Kaufman hits of 1926-28 (although he did produce Thornton Wilder's classic, Our Town). When Hecht & MacArthur returned to Broadway in 1932 with their second play, about an egotistically maniacal Broadway producer, they most pointedly did not give it to Harris. Instead, they invited Abbott to produce and direct Twentieth Century.

Unlike many popular hits of the day, The Front Page has remained a durable property which retains its power from generation to generation. It has been successfully revived three times on Broadway: in 1946, in a production directed by MacArthur; in 1969, starring Robert Ryan as Walter Burns (and Hayes stepping into the cast playing her mother); and the 1986 Lincoln Center Theater revival starring John Lithgow and Richard Thomas. The play has also been thrice-filmed, as an early talkie in 1931; in 1940 as "His Girl Friday" (with Hildy transformed into a woman reporter), starring Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell; and in Billy Wilder's 1974 version starring Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau. (The Criterion Collection will release a new, high-definition restoration of "His Girl Friday" in January--and will also include, as a bonus feature, the acclaimed 1931 film version.)

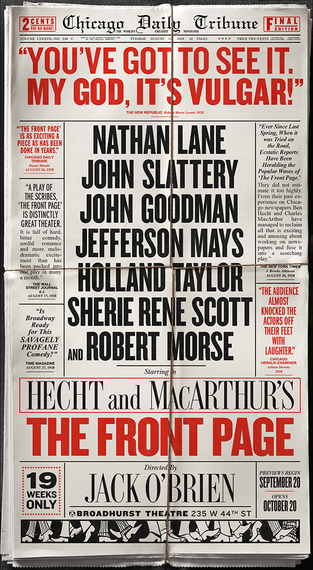

And now The Front Page is back on Broadway, with Nathan Lane, John Slattery and John Goodman leading a cast filled with some of today's most flavorful character comedians. But even more than the play's continued success in revival, it has had an outsized influence on Broadway. As Tennessee Williams, no less, put it: The Front Page "uncorseted the American Theatre with its earthiness and two-fisted vitality." As can be seen, even today, at the Broadhurst.

.

Hecht & MacArthur's The Front Page is now in previews and opens October 20, 2016 at The Broadhurst