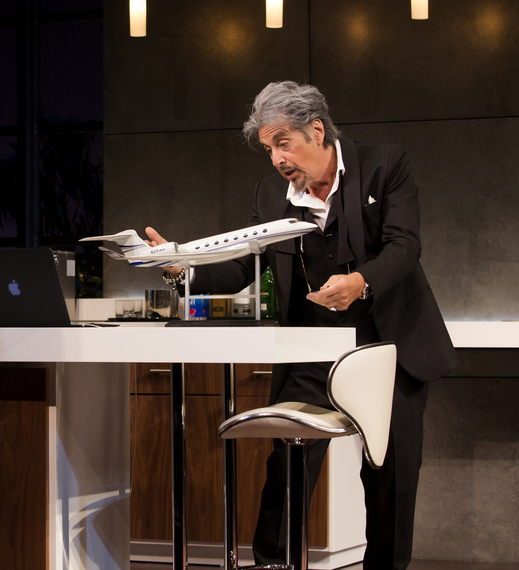

Al Pacino in David Mamet's China Doll. Photo: Jeremy Daniel

The unpredictable kismet that Broadway producers face deigns that sometimes you end up with something brilliant that no one, alas, wants to see. Contrarily, you sometimes come up with a decidedly nonworkable show that people nevertheless demand to see, in droves. We shall not discuss which is preferable, or more personally satisfying; we will simply point to Exhibit B at Schoenfeld Theatre, where Al Pacino is selling out in David Mamet's new play, China Doll.

Mamet has come up with something that is not quite an extended monologue, but almost so. Mickey Ross is an ultra rich old man living in what seems to be a penthouse in the clouds in what seems to be New York City. (Mamet doesn't specify, although he seems to cast several barbs at the current governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo.) His power seems to come from politics and money, and he has just spent $60 million on a personal jet; a new model, first one out of the factory. As the play begins, his carefully laid plans--designed to help him avoid a $5 million dollar sales tax bill--are subverted. Although that, it turns out, is the least of it. And he is not happy.

We learn this, or most of it, from Pacino-as-Mickey. Mamet provides a sounding board in the form of a long-suffering personal assistant named Carson (Christopher Denham), who brings newspapers, pours drinks, and fills in some of the blanks when Mickey permits him to get a word in. But China Doll is almost exclusively Pacino on the phone having endless conversations with unseen characters.

The advantages of this are several; for one, think of the savings on actors' salaries. (Perhaps not; Al, alone, is presumably out-earning the entire cast of Hamilton.) But the "Al alone" approach allows Mamet to write a mere half of every discussion. We never hear what the other people are saying, although one imagines that Mickey Ross--in context--doesn't listen to what other people are saying, anyway.

Mamet more or less gets by with this device in the first act, which outlines the purchase of the plane and Mickey's relationship with his very-much-younger and unseen fiancé Frankie. So much so that at intermission, you might well wonder why the early word-of-mouth on China Doll was so unremittingly negative. They said that Al didn't know his lines, but at the penultimate preview he seemed assured--although given that most of his lines are delivered with a Bluetooth earpiece in his right ear, they might well have been feeding him the dialogue, line-by-line.

In Act Two, though, we fall into a web of plotting that becomes more and more intricate. As we listen to Mickey's one-sided conversations with a lawyer and a political handler, we come to wonder whether we might benefit from visibly seeing who he is talking to and hearing the other side of the conversation. Al does, as always, have a tendency to mumble; with lines from other actors, we might better follow the plot. As the events spin out, we wonder if maybe the playwright is purposely keeping things enigmatic so he doesn't have to do the work of concisely figuring it out.

Ultimately, it feels like a stunt; by keeping the other side of the discussion silent, the playwright doesn't have to justify what Mickey is saying. Some of the leaps in the plot--concerning a blood feud with a young politician about some still-secret scandal, which Mickey covered up when the politico's father was governor--are so oblique that the play loses any steam it had. There are even some "smoking gun" papers literally pulled from the fire; and in typically melodramatic fashion, the "steel and aluminum" (i.e. bludgeon-worthy) model of the jet that sits on the counter turns out to be something more than just set decoration.

Al Pacino in David Mamet's China Doll. Photo: Jeremy Daniel

But after all is said and done--and after you add in contributions from director Pam MacKinnon, set designer Derek McLane and the hardworking Mr. Denham--you are left with Al Pacino. He plays the monstrous Mickey as a scrappy fighter who is on the border of realizing that he is no longer up to the fight. He roams about--and that earpiece allows him to wander across the stage at will, taking the conversation with him--as if he is walking in a fog. At some points, he might remind viewers of Pig-Pen, the "Peanuts" character who walks in a cloud of dirt; or maybe Peter Falk in a Machiavellian mood.

If China Doll has its weaknesses--and it has--it also has Al Pacino. And Al Pacino, on this occasion, is enough.

.

China Doll opened December 4, 2015 and continues through January 31, 2016 at the Schoenfeld Theatre