As New Yorkers go, you've just gotta love Alexander Hamilton. He was the perfect New Yorker because, of course, he was neither perfect nor born here. But, to evoke E.B. White, is anyone ever really from New York?

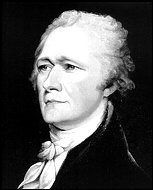

Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

On July 12, 1804, Hamilton was not just another New Yorker who almost "got whacked in 'Jersey" but was the great Alexander Hamilton, not even fifty, reduced to a limp life form in the bottom of wooden skiff being rowed back across the Hudson River from Weehawken, the life draining out of him after a duel with Aaron Burr. The rowboat successfully crossed the river to Manhattan, but Hamilton's fight for life ended in defeat at the Greenwich Village home of a friend the following afternoon.

Hamilton was forty-seven or forty-nine, his birth being a sketchy aspect about him. In fact, the subject of his birth was a far greater weapon used against him during his lifetime than the dueling pistol used by Aaron Burr at its end. From unwed parents and a father who quickly jumped ship, "bastard" was a label used by Hamilton's critics and saboteurs throughout his brilliant career. Big sticks, big stones.

Hamilton came to New York at age sixteen from the Caribbean island of Nevis with a blinding genius, brimming with ambition. Sent to King's College (now Columbia) by monies gathered by those in Nevis who so believed in his promise, Alexander Hamilton arrived in New York in 1773 and began his stunning ascent in a whirlwind, epic tale of crisis and opportunity, power and power play, from unclaimed son to Founding Father.

Doesn't New York set the greatest stage for this kind of story?

Plugging right in, this new arrival hard-wired his boundless energy to the circuit that was New York City, Albany and Philadelphia, becoming brighter and more powerful in the ensuing short years whether officially on or off the grid of influence. On it, Hamilton was his own Con Ed, and his carbon footprint was gargantuan.

Okay, you'll see what I mean when you check out Hamilton's work ethic and resume -- to start, it was on Columbia's campus within weeks of his matriculation that the young arrival caught the fever of the Revolution, immediately siding with the patriot cause, signing his first political treatise, "A Friend to America."

Out of college, his first real job was aide de camp to a General George Washington, under whose command Hamilton showed extraordinary verve in a lively bayonet charge at the Battle of Yorktown. After this courageous display, Hamilton became a Lieutenant Colonel.

In short order, Washington grew so close to the young man whose brilliance and savvy had become indispensable to him that he declared his aide the son he never had. Later, when General Washington got a better job, it could be said that Hamilton became the only son of the Father of the Country.

In addition to his remarkable connection to Washington, Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler, the daughter of Philip and Caroline van Rensselaer Schuyler. The Schuylers and the van Rensselaers were just about "it" in 1780.

In the ho-hum years that followed, Hamilton set up the Bank of New York in 1784, wrote the Federalist Papers in 1787, and became the first Secretary to the Treasury in 1789. By 1790, Hamilton had set up a financial debt absorption system for the colonies, which were all broke from the cost of the Revolutionary War. This highlighted the battle royale with another leading figure of the day, a quiet Virginian who happened to write the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

Even Hamilton's nemesis was as good as it gets.

A takeover artist, a control freak, Hamilton thought he was the smartest guy in the room, which he basically was, and was willing to go to the mat for what he wanted, even against the enigmatic and elegant first Virginian. Their quarrel, of course, was over the direction and tone the country would take -- an agrarian society of peaceful farmers, or a financial paper-based system swirling in a delicious broth (Jefferson might say putrid sewer) of debt and production, growth and trade, tariff and industry.

Ouch, this fight was epic. You thought politicians don't play nice today?

At death's end, Hamilton was by none lower than the Vice President of the United States, Aaron Burr, completing an arch of life and story from low birth to High Noon.

Yes, Alexander Hamilton was one perfect New Yorker: alarmingly brilliant, scrappy as any, touchy about reputation and honor, wholly driven to "get somewhere big." Lets put it this way: if Hamilton worked in midtown he'd never meet an escalator he didn't take and would never think the express elevator was anything but a private car.