Andrea Wulf begins her astonishing new book The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt's New World, with this:

They were crawling on hands and knees along a high narrow ridge that was in places only two inches wide. The path, if you could call it that, was layered with sand and loose stones that shifted whenever touched. Down to the left was a steep cliff encrusted with ice that glinted when the sun broke through the thick clouds. The view to the right, with a 1,000 foot drop, wasn't much better. Here the dark, almost perpendicular walls were covered with rocks that protruded like knife blades.

Alexander von Humboldt and his three companions moved in single file, slowly inching forward.

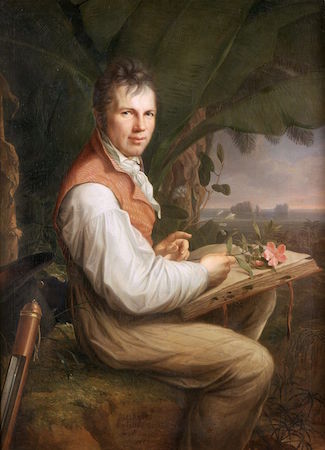

This took place on June 23, 1802, when Humboldt and his friends were climbing Chimborazo, a 21,000 foot-high volcano in the Ecuadorean Andes. It was one of innumerable such occasions of derring-do that marked Humboldt's life. But he was by no means simply a reckless explorer. Alexander von Humboldt was one of the greatest scientists of his time, a world-renowned figure for his many scientific discoveries, a revolutionary in his philosophical endeavors, a superb and extremely prolific writer and a friend and mentor to many other greats, not the least of whom were Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Thomas Jefferson, Simón Bolívar and Charles Darwin. When the king of Prussia, Frederick William III, introduced Humboldt to the Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, he suggested that Humboldt was "the greatest man since the deluge."

Reading this book, you will find out--in sumptuous, finely written detail--why Humboldt was so highly regarded by these and many, many other contemporaries. Even as a child in Prussia, he was an accomplished botanist, and the plant samples he later brought back from his many travels through far-flung territories in the old and new worlds formed the basis of contemporary botanical science. A noted geographer, he provided maps and geographic information about many areas of the world for which little or no such knowledge existed before him. He was a famous geologist as well as a discoverer and describer of bird and animal life everywhere he went. Humboldt discovered the magnetic equator, which is defined as "an imaginary line around the earth near the equator, where the lines of force of the earth's magnetic field are parallel with the surface of the earth and where a magnetic needle will consequently not dip." No one had understood this before him. He presaged what was to become an understanding of plate tectonics, and therefore of the makeup of the surface of the entire planet. Toward the end of his life, he made a close study of...well, everything, and wrote about it in his grand opus Kosmos.

Humboldt believed that the world is a single entity in which every element is as important as all others in the preservation of its own health. This was a revelation when he first proposed it, during a time when monarchies ruled, the earth was deemed inexhaustible, and Man supposed himself to be the ruler (and plunderer) of all he surveyed.

Because of the existential dangers present in the state of contemporary global weather and the destruction of the atmosphere, Humboldt's views continue to be directly instructive to this day. His dozens of books describing his travels, his findings and his ideas remain today central to the history of science and to the basis for our understanding of the dangers of global warming (which he first observed accurately in the early 19th century.) Tangentially, the way he wrote about the interconnectedness of all nature was central to the development of the Romantic movement in western European literature, art and music.

My favorite chapters in this book are those dealing with Humboldt's explorations of South and Central America between 1799 and 1804. He had made the acquaintance of a French botanist named Aimé Bonpland, and during those years the two men explored the great Orinoco River in Venezuela, Chimborazo and many other volcanoes, the Andes range, the vastness of Mexico, Cuba's island offerings and those of many other territories. The scientific data and observations that Humboldt and Bonpland brought back were among the most accurate and compendious ever gathered.

Humboldt met and was befriended by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson himself had a much noted interest in botany, geography, agriculture and scientific instrumentation, and Humboldt's findings in the new world were of great personal interest to him. Humboldt believed that scientific knowledge was above politics and should be shared by all for the benefit of all. His conversations and correspondence with Jefferson, nonetheless, allowed the president to obtain an accurate understanding of Mexican politics and territory that was later to aid (for good or ill) the United States's annexation of Mexican territory after the war of 1846-47. Generous in his sharing of so much information with Jefferson, Humboldt in large part gave the Americans the knowledge of what they eventually would obtain.

Politically, Humboldt was a deeply thoughtful, liberal-minded philosopher who advocated for representative democracy, the rights of indigenous people everywhere in the world and the notion that nature should be protected by liberal-democratic governments. The world, he would emphasize, is a finite, elegantly balanced place whose natural gifts must not be plundered. So Humboldt's explanations of the dependence of the world's matter, plants, animals and human beings on each other--explanations so vast and clear-minded--are more pertinent in our own time than ever before. Given the current state of perilous indifference to the ruination of the planet on the part of so many governments, Humboldt's work should be required reading for every politician.

Andrea Wulf's book is a paragon of research, thoughtfulness, considerable humor and fine writing. Her accomplishment in explaining this remarkable man to us is to be congratulated.

Terence Clarke's latest novel The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro was published last year. His story collection New York will be published this fall. He is director of publishing at Astor & Lenox.