Before IBM's Deep Blue made it cool, there was a chess-playing computer. In the late 18th century and into the 19th, it wowed incredulous audiences who couldn't tell, though many suspected, that a human was somehow behind it. For these Western European spectators, the machine's Turkish-inspired dress added to their perverse questioning of its humanness. History refers to this false automaton as the Mechanical Turk. Only after decades of its traveling show would it finally be revealed that a diminutive person, and extremely capable chess-player, had in fact been trained to operate the contraption from an inside compartment.

As a child who believed, for a stretch, that little people were actually moving inside my television, I could understand their fascination. But the Mechanical Turk lived when a computer was defined as "one who computes." In other words, yes, it was a chess-playing computer. It was also a human being. That one couldn't be entirely sure was magical to audiences, but it was also uncanny.

Automata continued to capture the imagination of Western intellectuals into the 20th century. In 1919 Sigmund Freud penned his essay on "The Uncanny," in which he delved into what's so discomfiting about these human-like machines. In his case, he focused on German Romantic E.T.A. Hoffman's ghost stories, which featured dolls coming to life a la Chucky from Child's Play. Freud postulated that Hoffman's dolls have a psychologically disturbing effect on readers because they are uncanny, meaning they are at once familiar and unfamiliar (heimlich and unheimlich).

It isn't always easy to tell whether an automaton is a human person. To complicate matters, computing technologies have become extensions of our own bodies, as opposed to mere tools such as a hammer, or even a more complicated mechanism such as a handgun. Some, including post-humanism theorist N. Katherine Hayles, believe that techno-toting human beings now use technology as prosthetics. We have merged with these machines, and it's the stuff of many a dystopian vision.

For his 2012 book, The Most Human Human, Brian Christian pretended to be a human being. He competed alongside both humans and computers alike to try to convince judges that his intelligence was not artificial. Known as the Loebner Prize, this "competition" recreates the Turing Test. In the 1950s, Alan Turing proposed that artificial intelligence, or whether machines can think, could be determined if said machines could fool scientists. Can we really be fooled into thinking a computer is a human being? It turns out that sometimes we can. Meet Cleverbot.

Brian Christian goes on to suggest that we face the Turing Test every day. Mostly, it's obnoxious. For instance, Sharon, my local Google specialist, calls me on the regular. I've learned, of course, that "she" is a bot. Human beings are, if I may, hard-wired with a remarkable ability to determine whether a sound is being reproduced through a recording device. In Sharon's case, it was easy to tell. Still, though, it was not a difference in kind but in iteration. The recording was obviously of a human being's voice. But a bot made the call and tripped the mechanism. Who is calling me?

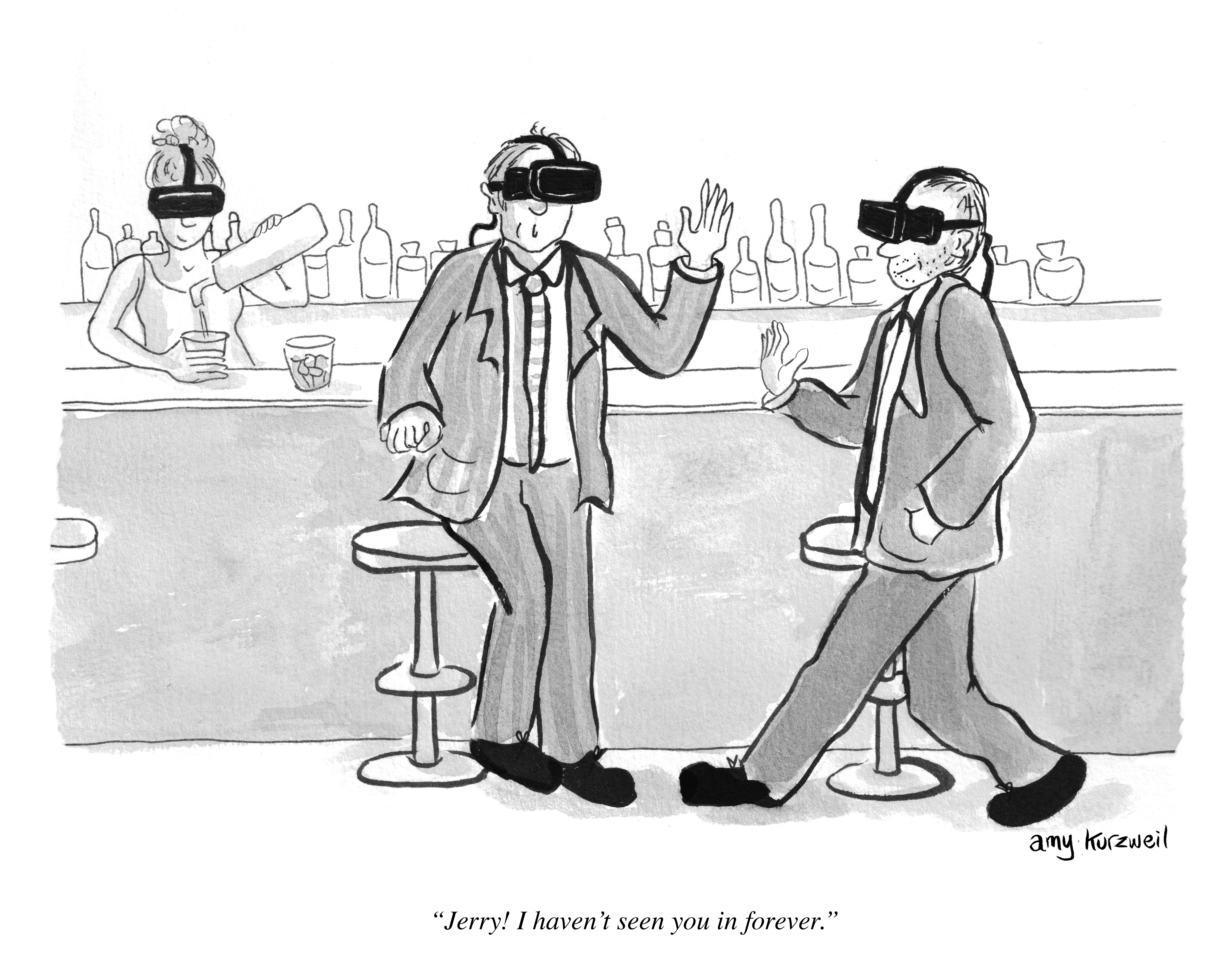

It will become harder and harder to identify automata, and I do not mean crazy-eyed dolls or local Google specialists. Our definitions of familiar and unfamiliar, culturally-defined as they obviously are, have shifted to include hybrid beings like Sharon. It is now familiar to find artificially intelligent technology functioning alongside human bodies, something that might've made Freud shudder. It is also familiar to find humans functioning alongside (and even inside) increasingly artificially intelligent technological bodies. What's uncanny is not that we can't tell whether it's human or AI, or in what proportion. We can't tell what it's been programmed to do to us. Is it trying to steal our identity or sell us a Snorg tee?