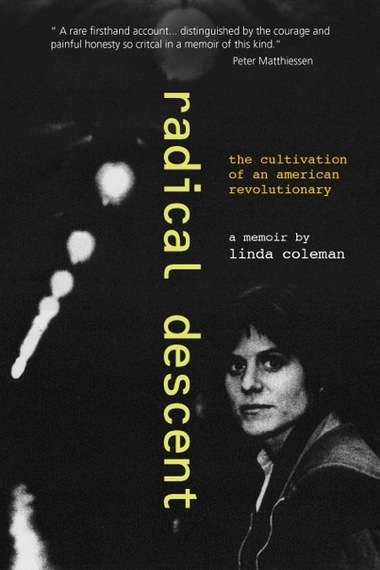

It took Linda Coleman 15 years to write her memoir Radical Descent: The Cultivation of an American Revolutionary, a soul searching and gripping account of her involvement as a young woman with a violent left wing underground group in the 1970s.

Coleman's story begins in October of 1974, shortly after her 21st birthday, when she walks into a small bookstore in Portsmouth, Maine with a red star above the door. Inside she finds just what she has been looking for: shelves of paperbacks on Marxism, social inequality, anti-imperialism, and women's liberation and a community of young activists who feel as passionately about these issues as she does. She pictures herself sitting by the bookstore bay window, quietly absorbing lessons on how to free humanity from capitalism's cruel grip. Instead, shortly after Coleman begins work as a volunteer in the bookstore (while employed as a nurse in a nearby hospital), the collective is ransacked by a local "death squad" and a coworker is raped. The next day, Coleman's new friends give her a gun for self-protection, a revolver that sits on her coffee table like "something wild out of its cage." Embraced by the small, secretive revolutionary cell behind the bookstore collective, Coleman soon finds herself bailing out fugitives, planning bank robberies, transporting dynamite and, on occasion, sleeping with the group's leader.

Coleman was a "solid sister" able to negotiate dangerous situations, but she was not necessarily revolutionary cadre material. "I don't like to fight," Coleman writes. "To be a revolutionary I couldn't just love, I had to let the hate in too."

It didn't help that Coleman, born into a patrician, wealthy Long Island family, was exceedingly polite and well brought up. She blushed when her comrades were rude to FBI agents; she couldn't gather the vehemence to call a police officer "a filthy pig" to his face and she insisted during meetings that no one get hurt or killed in the course of their planned robberies and bombings. Coleman's revolutionary zeal deeply conflicted with her innate sensitivity, her loyalty to her parents and her love for her grandmother, whose car Coleman borrowed for a bank robbery get-away. If some of this sounds vaguely quixotic -- and humorous -- it is.

Fortunately, the very qualities that make Coleman a hesitant revolutionary contribute to her talents as a writer (for many years she co-led a writing workshop in a women's prison). She has an eye for prosaic details like her licking a doughnut's sticky glaze off her fingers on an early morning visit to see a comrade in a penitentiary. And she is a keen observer of human nature examining her own messy motives and those of her comrades. The result of her relentless moral probing ultimately leads Coleman to reject her group's tactics and lifestyle, if not their social objectives. Quitting a revolutionary cell, though, is not nearly as simple as joining one, and the repercussions of Coleman's underground activities, and her friendships with people eventually incarcerated for violent crimes, haunted her for decades.

Benjamin Kunkel is the type of leftist Coleman's comrades might have dismissed as an armchair socialist. But that wouldn't be fair. Kunkel graduated from college in the 1990's when there were no more radical underground movements to join. By then the Soviet collapse and the apparent success of liberal capitalism had pummeled the left's faith and self-esteem. "The skepticism that replaced it was twofold," Kunkel writes. "The would-be revolutionary left seemed to possess neither a serious strategy for the conquest of power nor a program to implement should power be won."

Undeterred, Kunkel, with some friends, founded the left-leaning New York literary review, n+1, and now identifies himself as a "Marxist public intellectual," a risky confession in a country where being a Marxist - no matter how cerebral -- smacks of extremism. But Kunkel is not an ardent street activist and seems, at heart, more a Thoreau-ish utopian than a revolutionary.

His first book, a novel published in 2005, aptly called Indecision, ends with the young, naive protagonist falling in love and discovering that he is a democratic socialist, "a little apprehensive about the hard study of political economy" that lies ahead of him. In real life, Kunkel didn't flinch. He abandoned his literary life in New York and moved to Buenos Aires where he spent four years boning up on Marxist critical thought and political economics in general. The result is a slim, lucid book of essays called Utopia or Bust: A Guide to the Present Crisis, published earlier this year.

In truth, Utopia, is more about current Marxist theory, which Kunkel believes can best help us understand capitalism's recurrent crises, than it is specifically about 2008 or any alternative future socialistic scenarios (the subject, Kunkel informs us, of his next book). Kunkel's essays on the Marxist geographer David Harvey, the historian Robert Brenner and the anarchist anthropologist, David Graeber, - an influential figure in the Occupy Wall Street movement - provide historical economic context to the Great Recession and ongoing problems of excessive government debt, chronic unemployment and the like outside the United States. His other essays on literary critic Fredric Jameson, political philosopher Slavoj Žižek and art critic Boris Groys discuss such topics as the nature of neoliberalism and post-modernism, the end-game of capitalist ideology and the utopian aesthetics of Stalinist Russia. These are all thought provoking, but at times dispatched with such speed that readers not already familiar with these thinkers may find themselves floundering in Kunkel's prodigious intellectual wake.

In the end, Kunkel's point is not that Marxism or communism is the answer to our current predicament -- he is aware of Marxism's musty jargon and, not least, its disastrous 20th century political legacy. But in the face of capitalism's drive to commoditize the far reaches of the globe and every aspect of human culture and existence, Kunkel feels Marxist thought may be the most valuable means of interpreting the world and coming up with more ecologically sustainable, socially equitable alternatives.

It's true that Marxist thought has recently enjoyed a revival on campus and among activists. However, with the Occupy movement now three years behind us, and crowds of young consumers once again lining up to cheer the unveiling of the latest model cell phone, it's hard to believe that a Marxist brand of ideas will continue to find traction among the Millennial generation of activists, who have largely traded in ideology for technology. Their embrace of technology-as-transformation is, in part, predicated on the belief that this seemingly neutral instrument of change will lead to less bloody and painful revolutions than those of the past and avoid the daily "revolutionary" atrocities they have witnessed occurring abroad via Facebook or YouTube. The problem, as the public is becoming increasingly aware and as Coleman, now an ordained Zen monk, would readily point out, is that it is not the tools of change that matter in the end, but the motives of the people or organizations that own and control them.