"Fixing" education has been a focus of attention by education experts and the general public for decades. It is an ongoing challenge that has engaged some of our best minds and has stirred our most passionate advocates. But too often the "fix" has been a silver-bullet solution that has garnered mixed outcomes at best and occasionally drawn worse outcomes than if no bullet had been fired at all. Indeed the last couple of decades have seen there share of experiments with standardized testing, charter schools, vouchers and reducing class size experiments all with questionable results from an outcomes and return on investment perspective.

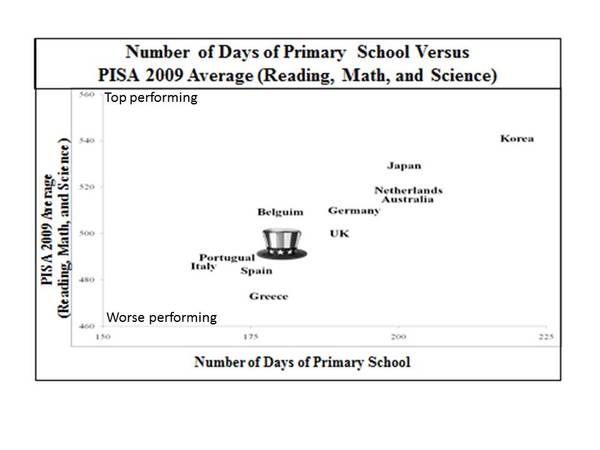

Longer school years is not a magic bullet, but it is one idea that seems very promising. For the 14 wealthy countries studied in Measure of a Nation, the data show clearly that there is a correlation of about ninety percent between the number of days a child attends school and the PISA exam scores (the PISA exams are a worldwide evaluation of 15-year-old pupils' scholastic performance in math, science, and reading). Although correlation doesn't mean causation, as every statistician knows, the strength of the relationship seen in the graph does seem to buttress the logic of more days in schools driving better performance, so it becomes hard to resist arguing that a longer school year would improve American academic performance. After all, the relationship is intuitive; as nearly every teacher will tell you, the long summer break sets children far behind in their learning.

In the American school system, there are no national standards for the length of the school year. Rather, this decision is left up to individual states. A majority of states require a minimum school year of 180 days; ten states require fewer than 180 days; and one state, Minnesota, has no minimum requirement for either the days of the school year or hours of instruction. The American minimums are in stark contrast to the 220 days averaged by top-performing South Korea and the 201 days in Japan, also a top performer. It seems clear that 20 percent more days of school provide more exposure to educational materials.

More generally, the long summer vacation in the American school year is not beneficial for student education, although it may be highly beneficial for some industries -- tourism, summer camps, airlines -- which rely on the long summer vacation for much of their revenue. American students typically are given ten weeks off for the summer, plenty of time to regress in their knowledge and study habits. Forgetting curves, developed in the late nineteenth century by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, demonstrate that memory retention declines exponentially over time, so the long American summer vacation takes a major toll on a student's ability to progress.

The recommendation of a longer school year for American students is not new. The US Department of Education made the recommendation in 1992, and President Obama repeated the call for longer school days and school years in September 2010, during an interview on a television morning show. Some charter schools have implemented more classroom time. The Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) academies, typically established in inner-city school districts, mandate some 60 percent more classroom time than traditional programs and add half-day classes twice a month. To add another month of school would require major changes to take place not only in our educational system but also changes in many of the for-profit industries mentioned above.

Longer school years are not a silver bullet, but they are one of the leading practices found in other countries that are excelling at primary and secondary education. Other leading practices include selecting top talent to become teachers, paying teachers well (to attract that talent), investing in ongoing teacher development (resulting in minimal turnover), making teaching a prestigious position, equalizing funding for education (so poorer students had similar educational opportunities as students from wealthier communities) and increasing enrollment in pre-primary education.

This article is an excerpt from the book The Measure of a Nation: How to Regain America's Competitive Edge and Boost Our Global Standing. A key goal in Measure of a Nation is to compare the United States to other wealthy countries, with the idea being to identify which countries are performing the best in each area of interest: health, safety, democracy, education and equality. In each of those areas, the countries that are performing the best are examined to determine which best practices might be applied here in America. In order to do this analysis, we selected the subset of countries that are both wealthy (nominal GDP per capita over $20,000) and have a population greater than 10 million (upper third of national populations, no city-state countries) as a comparison group. This comparison group consists of 14 countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Portugal, The Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Follow Howard Steven Friedman on his Facebook Fan Page