A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

Read Episode Twenty-Six: Why?. Or, start at the beginning: An Illness's Introduction. Find all episodes here.

When Robin Williams, one of the funniest people on the planet, took his life in August 2014, the tragedy rocked us all. The night after it was revealed he had Parkinson's, I dreamed I watched a man jump from a high window of the building across the street from me. I couldn't see where he landed and I was afraid to move closer to my window. Finally, I walked to the window and saw his crumpled body on the sidewalk. I'd been a huge fan of Williams since his first appearances on Mork and Mindy in the 70's; his death, only twelve miles from where I live, also hit close to home emotionally.

At the time of Williams' suicide, Parkinson's organizations and my fellow Parkies used the news to raise awareness about depression, one of PD's non-motor symptoms. To me, it seemed too simple to blame his death on the depression that can be caused by PD. Despite telling NPR's Terry Gross in 2006 that he had "gotten a lot out of psychotherapy," Williams went on to claim that he didn't have clinical depression. Yet for decades, he'd struggled with cocaine and alcohol addiction and later, we learned he'd been bipolar, a disorder that no doubt enhanced his warp-speed swings from deepest dark to hilarious during performances. As he said, "A comic feels all things -- he has to." Whatever his mental health diagnosis, I believed it was his intense scrutiny of what it means to be human -- and what it meant to be Robin Williams -- that made his future with Parkinson's seem unendurable. His identity depended on his rubber-face animation, quicksilver gestures and hyperkinetic tongue, his thoughts turning on a dime. These happen to be precisely the things that Parkinson's takes away from a person. "Who will I be without them?" I imagined him thinking. For someone with such a passion for performance, I reasoned, Parkinson's might just be the worst possible disease.

But it wasn't the worst. Three months later, an autopsy revealed Williams had Lewy body dementia.(LBD). LBD is the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer's and is as common as Parkinson's, affecting 1.3 million people in the U.S. Because LBD, like Parkinson's, involves the death of dopamine-secreting neurons in the brain, causing motor symptoms, someone with LBD might first be diagnosed with PD, as was the case with Williams. But unlike PD, the non-motor symptoms of LBD develop rapidly. Patients usually experience a steep decline in cognitive abilities as well as heightened emotional states like fear, anger and depression. Hallucinations and paranoia are also common in LBD.

When all we knew from the press was that Williams had had Parkinson's, it seemed tragic to me that he'd been unable to find fulfillment in everything he'd already given to the world, or make peace with a possible future of "just" being a father, a husband, a friend -- albeit a slower, quieter one. But learning he had LBD radically altered my understanding of his desire to end his life. He wasn't just shaking, slowing down and losing his edge; already, he was imagining terrifying things and hiding watches in a sock. How would any of us feel, knowing we would be living with such demons until death? This is one of the key questions spurring refinements to Death with Dignity laws that will hopefully allow humane alternatives to suicide in cases of severe or end-stage dementia.

When people ask what scares me most about Parkinson's disease I tell them: the possibility of cognitive decline. I can hardly bring myself to say the word "dementia."

Until fairly recently, Parkinson's was described as a movement disorder that affects the motor circuits of the brain. But now we know that as the disease's brain changes spread, other circuits are also impacted, causing symptoms like depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances and cognitive issues. Unlike in Alzheimer's, which is associated with increasingly severe memory problems, cognitive decline in Parkinson's is mainly manifested by an impaired ability to focus, multitask, plan and efficiently process and communicate information. People with PD might also have difficulty processing visual information and find themselves disoriented when, for example, navigating a busy supermarket. Scientists estimate that in 20% to 80% of people with Parkinson's, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will develop into dementia. This squishy statistic means that on a good day, I focus on the 20%. On a bad day, I feel doomed to become one of the 80%.

The fact is, dementia is also what most scares my friends who don't have Parkinson's, since now that we're in our 50's and 60's, all of us seem to have had at least one parent or sibling who's struggled with Alzheimer's or other dementia. Sometimes I look at it this way: we're all aging, some of us faster than others because our cells are misbehaving. Apparently, until we're around 55, our bodies are pretty good at repairing DNA damage. But studies have shown that around age 30, our major organs are laready going into decline. There's plenty of debate, but some studies indicate that cognitive abilities are at their peak between age 30 and 40 and begin to diminish in our 50s.

The difference between having a disease that can cause cognitive impairment and not is that I'm always in the lookout tower, scanning my brain for mental marauders. When a friend can't remember the name of a movie she saw last week, she slaps her forehead and says, "I hate getting old!" When I can't remember the name of the movie I saw I think, "Oh no, it's happening!" Then there are the disappearing words: More and more when orally describing something, I've been having trouble retrieving a word that I know would precisely fit what I'm trying to convey. Can I blame nervousness, fatigue, natural aging? Or is it Parkinson's? My word-fishing has irritated me to the point that instead of moving on and settling for a more imprecise word ("thing" is a tempting stand-in), I sometimes stop and wallow in my frustration, even soliciting the help of my listener. "Impeccable?" he will suggest. "Meticulous?" "No, no, that's not quite it," I'll say, and then realize that any further deliberation will surely confirm that I am indeed becoming demented. Too, there are all the facts that I forget. I'm quick to Google, yet sometimes I will resist, forcing myself to dredge up an elusive fact from my deepest storage lockers, just to prove to myself that I can. It's like digging for clams though, because I don't actually know if the fact is still down there, in the muck.

Fourteen million of the 79 million boomers in the U.S. are expected to develop some kind of dementia; I am six times more likely to than my arm-swinging (non-PD) friends. And if I do, it may very well be the kind of dementia that plagued Robin Williams.

Why, exactly, is this? (I'm glad you asked!) It's all about a protein called alpha-synuclein. A story about Parkinson's disease would be incomplete without mention of alpha-synuclien -- sort of like Star Wars without Darth Vader. Alpha-synuclein is a protein found throughout the body but most abundantly in the brain. Its exact function is not fully understood but it's known to be essential for communication between cells. Like the villains in many stories, alpha-synuclein makes an important contribution to our health and wellbeing until it's corrupted by bad influences. Once this happens, the protein forms gangs that become intent on ruining the brain, one neighborhood at a time.

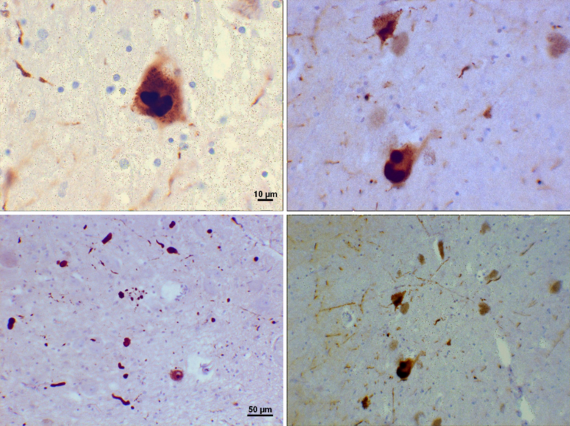

Combat metaphors aside, what happens with the protein alpha-synuclien in people with Parkinson's, multiple system atrophy (MSA) and Lewy body dementia (LBD) is that it mutates, or misfolds, creating a toxic version of itself. (Alzheimer's involves a similar process, but with a different protein, beta-amyloid.) The misfolded alpha-synuclein then clumps together, forming aggregates called Lewy bodies that infect brain cells, causing them to die. Infectious proteins that spread disease within the body in this way are known as prions. Not only do people with PD, MSA and LBD generate too much of the misfolded alpha-synuclein but also, their brains are unable to properly dispose of toxic and dead cells, so they build up and continue to do damage.

In 2015, alpha-synuclein became even more villainous. Scientists discovered that the unique strain of alpha-synuclein found in the brains of people with Hadley's disease, multiple system atrophy (MSA), was able to spread disease to mice who came into contact with infected brain tissue. Fifty years ago, it was thought that only viruses and bacteria could transmit disease. But during the decades since then, it was discovered that in cases of the first identified prion disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, a neurodegenerative disease that is a human variant of "mad cow disease," misfolded proteins within the body that replicate could spread disease to other animals and humans. This discovery about MSA raises new concerns about surgeries involving contact with infected brain tissue. Since many people with MSA are first diagnosed with Parkinson's, some undergo deep brain stimulation surgery (DBS), like my Facebook friend, Jane. Neurosurgeons now will be taking extra precautions during and after brain surgery, especially because unlike most bacteria and viruses, proteins are very hard to kill. Will further research uncover that Parkinson's, too, is transmissible? Stay tuned...

Since the living brain is relatively inaccessible, researchers are investigating other areas of the body where alpha-synuclien occurs, trying to determine, among other things, what species of it forms the toxic aggregates found in neurological disease. One place the protein shows up prominently in those with Parkinson's is in the gastrointestinal tract, where scientists have hypothesized it might first misfold and form clumps, then travel on the vagus nerve to the brain. The evidence that most people with PD experience gastrointestinal symptoms, sometimes many years before their diagnosis, adds weight to this possibility and might help doctors diagnose PD much earlier.

I found this research compelling. So last year, I brought it up with the gastroenterologist who would perform my routine colonoscopy. Lying on the gurney while the G.I. doc, a man in his fifties, and his three young assistants bustled around me preparing for my procedure, I said, "I have a question: If you find a polyp, or have to take tissue samples for any other reason, could you test it for alpha-synuclein?" I didn't really expect him to agree to do this, of course; I really just wanted to hear his take on the research.

The doctor whirled around to look at me, amused and clearly stumped. I went on to explain. "Really?" he said. "I haven't heard about that."

One of the assistants said, "Wow, that's interesting."

"You guys," I said. "You need to keep up on this stuff." I laughed so they'd know I was teasing.

"Hey," the doctor said, "I'm a gastroenterologist, not a Parkinson's doctor."

I was struck by his remark, not just because (he was defensive and) he was unfamiliar with the research, but also because he seemed to be saying that it was irrelevant to his practice. And yet, the G.I. tract is his territory, the place he goes to work every day, and we're talking about how it might hold a major key to understanding devastating neurological diseases. The gut is connected to the brain! How cool is that!

I'm betting that soon, gastroenterologists will be mining more than polyps. Nearly every scientist working in Parkinson's research has taken on the challenge of alpha-synuclien, exploring how they might bust up Lewy body gangs or keep them from forming in the first place. Other strategies might involve increasing the brain's capacity for disposing of toxic cells or somehow inhibiting the production of alpha synuclein. A vaccine that activates the immune system to produce antibodies against the protein is moving into phase two of trials. But scientists first will need to determine the amount of alpha-synuclein the body needs to function normally.

The more we understand about alpha-synuclein, the sooner there will be, for the first time, disease-modifying therapies that can slow or stop the progression of Parkinson's. And, what works for Parkinson's will also make a profound impact on the future of MSA, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer's. Perhaps it's not too hopeful to look forward to a time when "losing my mind" is mostly just a figure of speech.

Episode twenty-eight of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress will be published in two weeks. You can also follow the serial here.