A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

Read Episode Thirty-Three:In the Clench of Critics. Or, start at the beginning: An Illness's Introduction. Find all episodes here.

In the days leading up to the January 7, 2015 unveiling of the Montana Women's Murals at the Montana State House, Hadley racked up some serious numbers. 18: the hours she painted every day. 18 was also the number of paint layers on the murals' elaborate borders, for which she recruited help from friends and her daughter, Sarah; they took 245 hours to complete. Hadley wore out 38 small brushes articulating the paintings' finest details.

When she wasn't painting, Hadley slept on a mattress she'd moved upstairs to her studio so she wouldn't disturb John. Her eyes burned and blurred, her body throbbed, her mind numbed as she applied every ounce of focus to the canvas in front of her. On the afternoon of January 5, she texted me.

Then, she shepherded the two 5 x 10 foot murals to Rick's Auto Body, where they were powder coated, a protective treatment that would eliminate the need for plexiglas once the panels were mounted at the State Capitol Building.

I didn't have to twist my friend Cary's arm to fly to Helena with me for the mural unveiling. An artist herself, she was very excited to meet Hadley and to document the event with her camera. On the second leg of our flight, I noticed the man in the seat across the aisle from me had a hand tremor. Other afflictions cause tremors, but after a couple more furtive glances, I noted he was wearing a rubber bracelet imprinted with the words "whatever it takes to beat PD." He was young to have PD and was flying to Helena; he had to be a friend of Hadley's, I reasoned. I touched his arm lightly and asked if he was headed to the unveiling. He laughed. Yes, he said; he was coming from Portland. Thanks to social media, the world of people with YOPD is not that big.

Temperatures were in the teens in Helena and for the first time in more than thirty years, I drove on roads packed solid with snow and ice. The landscape shone like satiny white frosting. Navigating our hotel's ice-paved parking lot in our smooth-soled city boots, Cary and I must have looked ridiculous, barely keeping our feet under us.

The next day before the unveiling ceremony, we met Hadley at the Victorian B & B where she was staying with John and Sarah, her mother, Jana, and her uncles and aunts from Texas and Nebraska. She appeared calm and serene -- a heroic demonstration, considering the heavy strain she'd been under and the important public performance she had ahead of her.

It wasn't until Cary and I arrived at the imposing Montana State Capitol -- like so many other capitols, domed, Neoclassical, built at the turn of the 20th century -- that I felt the full significance of the contribution Hadley would be making. The muscular building's sandstone and granite merged with the grey wash of winter sky, smeared now with sunset pink. Inside, all pretense of solemn restraint dropped away and we found ourselves in an enormous rotunda whose classical details were painted like a children's carousel: red, gold, green, yellow teal. I welcomed the space's vibrancy and warmth on the bleak, frigid day. Historic paintings adorning the rotunda reminded me of the reason women legislators had determinedly lobbied for the Montana Women's Mural. Four circular paintings on the dome illustrate a Native American Chief, an explorer and fur trapper, a gold miner, and a cowboy. Other paintings in the space depict Lewis and Clark and President Ulysses Grant wielding a sledgehammer to drive the "golden spike" that announced the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Women were conspicuously missing from the narratives on display, despite their influential roles in America's history. Montana boasts the first woman to serve in the U.S. Congress, Jeannette Rankin, who won her seat in 1916 and helped to pass the 19th Amendment that gave voting rights to women.

My legs were shaky as Cary and I climbed the grand staircase rising inside the barrel-vaulted hall. We were there early to claim our standing spot against the stair balustrade on the third floor. There we'd have a good view of the program's speakers and both murals -- now covered with blue cloth -- that hung on facing walls on either side of the open stair. We people-watched until Hadley arrived with her family. Finally, Hadley come up the stair, holding the rail and taking each step very slowly, greeting people she passed.

By the time the dedication ceremony began, more than 250 people had jammed the stair and the space that wrapped around it. Montana's first lady, Lisa Bullock, was the first to speak, calling the mural unveiling a "monumental moment." Julie Cajune, who had been especially helpful to Hadley with her research on Native Americans, spoke from the heart about both the murals and Hadley. "Not only is Montana the only state to recognize American Indians in its constitution," she said, "but now our state capitol recognizes that women have been the sinew to keep body and soul, community and spirit together...Women have not just been homemakers. They've been healers, pharmacologists, teachers, spiritual people and warriors. Women have done everything..." When she spoke about Hadley, Julie audibly fought back tears. She told the crowd that she and Hadley had worked "soul to soul." "I want to tell you what a fine artist she is," she said. "But also what a fine human being she is." She expressed appreciation for Hadley's genuine desire to explore the customs of Native Americans in order to paint their story. "Thank you," she said to Hadley. She spoke a few words in Salish, her tribe's language, then presented Hadley with a handmade quilt that she wrapped around her shoulders. By that point, I was the one holding back tears.

Hadley stepped to the microphone with Sarah by her side. "It's truly an honor to have you all here," she said, thanking the crowd. She spoke of how meaningful the project was for her as an artist, a lifelong Montanan and a collaborator with the many who made the murals possible. She read her artist's statement:

The generations of women in my family have set examples and carved paths for my mom, my daughter, and me to have the life and experiences we live today. That is what this project is about. This piece is about the generations of women in Montana who built families and contributed to their communities, to the economy, and to politics by working together to build strong communities for generations to come. It is not about one single important woman, but about all women. It is a broader picture of women. Hopefully, any woman can look at these images and see a piece of herself in them.

Other dignitaries contributed comments to the unveiling ceremony, including Montana Senate President Debbie Barrett, Speaker of the House Austin Knudson, as well as Senator Diane Sands and former Senator Lynda Moss, who partnered to get the Senate bill passed that authorized the mural commission.

A lot of pomp and circumstance -- it was a government affair, after all -- but knowing the monumental effort that had gone into the murals, to me, no ceremony would've seemed too grand. The murals waited behind their blue shrouds; the suspense in the hall was palpable. When the curtains were finally pulled away to reveal both panels, the crowd erupted in applause and exclamations. The Montana Women's Chorus sang: "A woman's voice raised up in the silence can be heard a long way...Revolution starts in a circle rising up from the ground. We believe in the power of women to turn this world around."

Cary sprang into high gear with her Nikon, turning it on the crowd and the murals with the rigor of a professional journalist. I couldn't take my eyes off the paintings. From a distance, they radiated warmth and liveliness and seemed perfectly at home, as though they'd always hung on those walls. Hadley had told me she'd made sure that her colors would complement those of the building's architectural features, including the enormous stained glass skylight of the barrel vault. This had been masterfully accomplished. Close up, I marveled at the abundance and variety of activities taking place in the murals' scenes and the precision and sumptuousness of the details.

Women's History Matters, a website created as part of a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of women's suffrage in Montana, explains the history brought to life by the two murals:

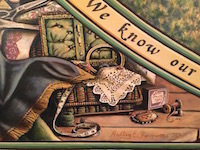

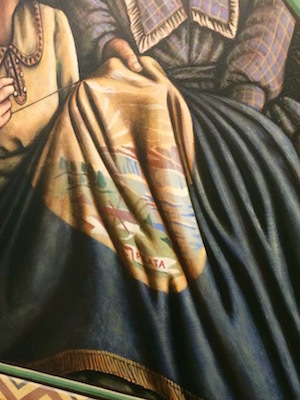

Panel one, titled "Women Build Montana: Culture," is set in the spring in the late 19th century. It depicts Native women having come to a homestead to trade for goods. In keeping with the theme of Montana women as community builders, the scene portrays a meeting ground in which women acted as traders and cultural brokers. Montana women, Natives and newcomers, often lived quite near each other, trading knowledge and offering support as well as goods. The four corner vignettes depict women and children engaged in the paid and unpaid labor that helped build Montana... Women are digging bitterroot, an important food source for Native peoples and the plant that would become the Montana state flower. The two Euro-American women stitching a Montana flag, inspired by a historic account, represent the mixing of domestic arts and formal politics. Children harvesting sugar beets represent the Mexican-American families who contributed to the economy and community of eastern Montana. The Native mother and daughter beading and preparing a hide illustrate the teaching and learning of traditional arts across generations.

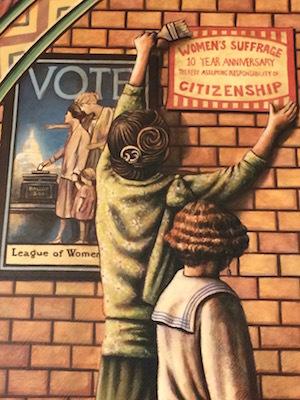

The central scene of the second panel -- which is titled "Women Build Montana: Community" -- is set in the fall of 1924, in an eastern Montana town. While women won the right to vote in Montana in 1914, that right was not extended to Native women until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act. The scene marks the tenth anniversary of Montana women's suffrage and acknowledges the year in which Native women gained citizenship and the right to participate in formal state politics...The vignette of a woman canning fruits references not only the work of homemakers, but the important role of home extension agents. The telephone operators personify Montana cities' and towns' clerical workers and women as labor union members: the first union of telephone workers in America was organized in Montana. Thousands of Montana women joined voluntary associations that supported women's education, here represented by members of the Montana Federation of Colored Women's Clubs giving out a college scholarship. Education is also depicted in the vignette of a Native woman teaching botany. Botany was one of the few sciences that welcomed women, and Native women's knowledge of the medicinal and nutritional uses of Montana plants was, and continues to be, important to both Native and newcomer communities.

After the ceremony, Hadley was quickly swarmed by reporters, TV cameras, friends and family. She never sat down. I figured adrenalin was propping her up, keeping her from collapsing or even fainting -- her specialty. I inched toward her through the crowd and caught her mother's attention; she had tears in her eyes. When Hadley's father, a history professor emeritus, embraced his daughter, he did too. "Just imagine," he said. "They'll have a Hadley Ferguson file in the state archives."

I finally got close enough to give Hadley a congratulatory hug. When we made contact, I felt as if the seams keeping me together might split. "I can't believe you pulled this off -- they're...you're amazing!" I burbled over her shoulder. With her usual modesty, Hadley said, "I can't believe it either. They turned out the way I wanted them to. I'm just so happy."

The seams gave way; I cried. Not "Oh, I'm so happy for you" tears, though I was thrilled for her. They were the kind of tears that surge from your innards when you or someone you care about has just survived a near-death experience. Tears full of knee-wobbling relief and joy, mingled with the pain of everything I knew Hadley had been through and what she still had ahead of her. Creating the murals had been a yearlong marathon, both depleting and sustaining, during which Hadley had courageously kept her illness, multiple system atrophy, outside her door. It had banged hard on that door, but she had another calling. And she emerged victorious, unveiling a gift to Montana, to women everywhere, that's nothing short of astonishing.

The real miracle? Not the masterpiece revealed, but rather, the multitudinous, veiled minutes of its making.

Find all episodes of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress here.