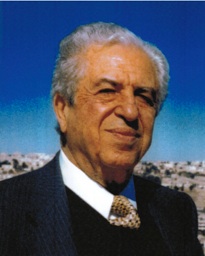

My father, Sion Levy, was ninety-years-old when he was born again on Thursday, July 8 at 5:30 PM. No, my father was not a born again Christian, but an avid Jew and a Zionist, who did not believe in death, but in a cycle of rebirths--the joining of sperm and egg, birth of a baby, and a time when the soul sheds the burdensome weight of the body and attachment to materialistic stuff to enter a better world. In question as to why not commit suicide so as to arrive at that "better" world sooner rather than later, he would check you with his piercing gaze and ask, "Does raw fruit plucked before its time taste good to you?"

My father lived on his own terms.

He was devoted to the Torah and often referred to passages as examples of how his children should conduct their lives. He would, when necessary, interpret a specific Parasha, a section of the Torah, to make it relevant to our times and to any specific point he intended to prove. Enough for him to suggest the logic behind such and such Halakhah--the root of Halakh in Hebrew is to walk or to go and the literal translation a way of conducting one's life--and any further debate, or God forbid, questioning of his opinion was a lost case. The word of the Torah was sacrosanct. And that was that. My father rarely, if ever, budged from his religious, Zionistic, and personal medical beliefs, yet he proved admirably resilient when confronted by the many obstacles life tossed his way. He left Iran and a large flourishing family behind to go to Israel with my mother, where he joined the Israeli Army in a war that culminated in Israel's Independence. Twelve years later, he moved his family back to Iran, where he created a prosperous business with his father and brothers. And then again, the Islamic Revolution forced him to abandon his home and substantial financial assets and move his family to safety in America. At the age of sixty, with little knowledge of the English language, he settled into a foreign country and culture, where he repeatedly encountered personal, familial, and financial difficulties. A lesser man would have buckled under. Yet, my father behaved as he often advised us to: "During a storm, bend low so the high waves wash over you, rather than fight waves that might break your back."

My Father died on his own terms.

We checked him into the hospital on Monday for a series of medical tests he questioned and argued against every step of the way, believing that one should be his own doctor and that medical establishments tended to create added health problems--pothole after pothole nearly impossible to climb out of. And he was often right. A nurse gave him a baby Aspirin, which he pretended, quite convincingly, to swallow with a few sips of water. When she left, he handed me the pill. "Toss it in trash. I'll bleed if I have this. Can you believe it? I entered the hospital a healthy man and in a few hours, they made me sick."

The next morning, he embarked on yanking the IV and other tubes out of his arms and demanded to leave the hospital. He wished to be re-born at his home, not in a hospital. The doctors had no choice but to discharge him. My sister drove him back home as he thanked her profusely.

He left a detailed will as to how he wanted his wife and six children to sit Shiva. He was to be buried as soon as possible, according to Jewish law, Halachah. His family was to wear white during Shiva. His memorial service was to be held on a Sunday from four to six in the afternoon at Sinai Temple. He chose the speakers. The Shiva at home was to be a respectful affair and the ceremony after memorial services was to be simple.

And all the elements, the heavens and earth, came together to make his wishes come true.

Sinai Temple rallied to make every step of this difficult process occur according to my father's will. The burial took place at three in the afternoon the next day on Friday, a few hours before the Sabbath. Despite such short notice, a surprisingly large contingency of family, friends, and members of our community attended the ceremony. We, his children, believed Sunday was too soon to hold a memorial service and tried to secure the main sanctuary either on Thursday, Wednesday, Tuesday, or Monday. The only available time was on Sunday, four to six pm! My father would not allow his children to deviate from his wishes. To our surprise, we heard from Rabbi David Wolpe that my father had visited him seven years ago to specify what he wanted his rabbi to say at the memorial. The conversation was held in Hebrew, a language my father loved and considered the language of his people. He wanted to be remembered for his commitment to Israel and considered the name Sion perfect for him, since his life was all about Israel. He saw the beauty in the world, but also the bad and was sometimes disappointed in others when they failed to reach their potential, as was the case with himself, he confessed, since he was sometimes inconsistent, not as kind or patient as he wanted to be. It was important for him to be remembered as he was, not as others wanted him to be, so he went to see his rabbi when he was fine and perfectly healthy. Years after, Rabbi Wolpe said, the two saw each other, but the conversation was never again mentioned. The conversation had been had, it was done.

Appetizers were served after service that Sunday, but an hour, perhaps more, passed and there was no sign of dinner. My father was present, chiding, ordering me to step up to the stage and inform more than three-hundred friends and relatives that dinner was not part of his agenda. And so I did. No microphone in sight, my heart pounding, I raised my voice above the din and shared my father's will. Serving dinner, it seemed, was a deviation from his wish to hold a simple affair. I had hardly stepped down to accept a needed glass of water from a friend, a gesture I appreciated enormously, when dinner arrived. Too late for those still present to enjoy, but not too late to be dispatched to a retirement home of my father's choosing.