Newsflash: Before the Internet, artists used NASA satellites to communicate and collaborate with each other across the country. This truth, which sounds stranger than fiction, was achieved by video pioneer Liza Béar and her colleague, Keith Sonnier. After this project, Liza founded Communications Update, later renamed Cast Iron TV, which was a weekly artist public access program that ran continuously on Manhattan Cable's Channel D from 1979 to 1991. Liza and another filmmaker, Milly Iatrou, produced and contributed segments for this program. On July 25, they will present individual segments cablecast in the Communications Update 1982 as part of the exhibition XFR STN at the New Museum. Here is a Q&A about their role as artists during that time.

Liza, you are one of the founders of Communications Update. What gave you the idea to start an artists' program on public access cable television?

Liza Béar: I'll backtrack. The late '70s was not just about Punk and the Sex Pistols, great as they were. There was also a burgeoning telecommunications revolution pre-Internet. I became aware of it because in 1977 I'd done an ambitious interactive project with Keith Sonnier linking East and West Coast artists via CTS, a NASA satellite. The two-way transmission was relayed to cable systems at both ends. We hoped to set up a permanent satellite/cable network for artists to interact directly, exchange work and ideas just like the corporations and the military do, but no one would fund a bunch of experimental artists without major institutional support. A public access cable TV show seemed more practical.

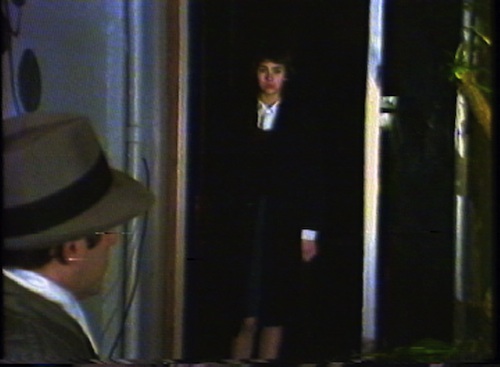

Stephan Balint and Boris Major in "A Matter of Facts," 1982 by Eric Mitchell

Milly, what attracted you to Communications Update/Cast Iron TV?

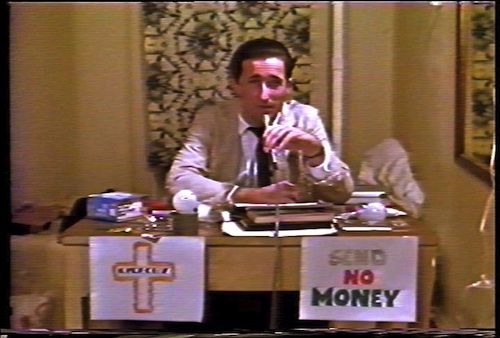

Milly Iatrou: We met through another artist, a mutual friend. Liza invited me to produce a show for the series, and I jumped at the chance. It was very exciting to make something for a potential audience of thousands. Also, my partner (and now husband) Ronald Morgan and I wanted to do a parody of late night television evangelists who seemed to have taken over cable TV at the time, and I thought, "What a perfect venue," for what eventually became The Very Reverend Deacon b. Peachy series.

How did the programs get made?

MI: In those days very few people could afford their own production gear. By forming a video co-op with about 10 other artists, we could rotate the use of the equipment. We had a Sony 1610 color camera and 3/4 inch portapak, a cumbersome battery belt, wooden fluid head tripod and industrial microphone. Everyone had three days a month to shoot. Members of the co-op often crewed on each other's projects. It was all done on the honor system and for the most part it worked out.

LB: I still have that tripod in my East Village apartment.

MI: Editing was difficult and done on-line with an engineer. Titles were made with a character generator -- very time-consuming. Now we can do that and much more on a laptop using software like Final Cut Pro and ProTools, which are relatively inexpensive and easier to use. Of course, I'm looking back from a perspective of someone who's been working on Hollywood feature films for more than 20 years, working on sound mixes with thousands of tracks and a crew of dozens of sound editors. Over the years I've had to learn many non-linear editing systems and software.

Ron Morgan in "The Very Reverend Deacon b. Peachy," 1982 by Iatrou & Morgan

LB: We kept the C-Update logo at Electronics Art Intermix, a pioneering downtown media center, where most artists did their editing. Before we formed the co-op, we'd travel to WXXI-TV in Rochester, NY which loaned video equipment to artists. We'd lug the gear over five-foot banks of snow.

MI: We had minuscule funding from the Media Bureau and occasionally from NYSCA (New York State Council on the Arts) for post-production. Each artist got $200 for a 28-minute program for C-Update.

LB: The show was at least 80 percent self-funded by its contributors. Occasionally scheduled programs weren't finished on time. Each week's tape had to be bicycled to Manhattan Cable at 120 East 23rd Street a week ahead of airdate or MCTV wouldn't run it. Our time slot was Wednesdays 7:30pm right after the 7pm network news.

MI: Luckily I'd just received an NEA video fellowship, which helped supplement my expenses.

Liza, what were your goals with the project?

LB: My goal was to move the goal post. We all wanted to go beyond the clichés of commercial television. Change not only the content, but the tone -- be active makers of information, not just passive recipients. Address topics not dealt with by the mass media. Reveal shared sensibilities, not just in SoHo or the East Village. Sanja Ivekovic and Dalibor Martinis compiled two half-hour programs by Zagreb artists; Vicky Gholson made several in Harlem and in New Orleans Janny Densmore made "Algiers Killings," part of which was later incorporated into a CBS 60 Minutes special.

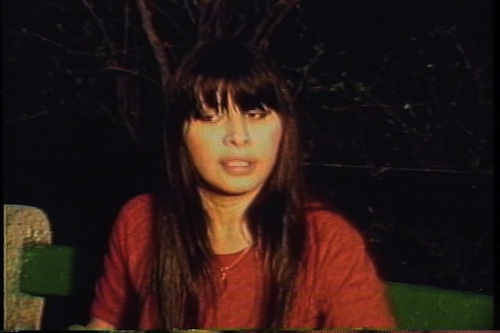

Occasionally the opportunity to show acted as a prompt for the making of a video. For instance, Robert Burden had been helping me edit Oued Nefifik: A Foreign Movie, which I'd shot on Super 8 and transferred to video. Realizing he was a brilliant editor, I invited him to the show -- he and his partner Dictelio Cepeda made "Crime Tales" for the Spring 1982 series. Film director Eric Mitchell made his first television work, "A Matter of Facts," with Squat Theatre. Artists Mark Magill and Stephen Torton and many others also made their first videos for the show.

Are there any modern day artist groups comparable to Communications Update?

LB: Many of the other artist TV shows at the time like TV Party, The Taylor Mead Show, Potato Wolf, All Color News, The Willoughby Sharp Show were live shows. Now most producers have internet blogs or websites. But Paper Tiger TV, founded by Dee Dee Halleck and developed as a collective, recently celebrated its 30th anniversary on public access. Dee Dee, a media activist and filmmaker, had been a frequent early contributor to Communications Update. When C-Update was renamed Cast Iron TV, it kept its political edge with programs such as "The Algiers Killings", Stephen Torton's "Empty Space is Wasted Space", Franck Goldberg's "Who Killed Michael Stewart" which investigated the killing of a graffiti artist by New York City transit police, "Ain't Half Racist Mum," by Campaign Against Racism in the Media, which explored racism at BBC. But the series primarily became a forum for artist experimentation and was much more eclectic.

MI: The situation now is completely different. With the internet, one doesn't need an intermediary at all. You just have to upload, inform through social media and if people are interested they will see it.

I grew up in the suburbs and romanticized NYC through the eyes of child watching Sesame Street. Milly, can you tell me what New York City in the 1980s was like for you?

MI: For me it was exciting, inspiring and a little dangerous. Many artists lived in a small area downtown and we would run into each other at the post office, copy place, clubs, etc. And that's usually how opportunities to show work and collaborate presented themselves.

Liza, what were some of the pivotal moments during the time-span of the show, 1979-1991?

LB: Well, I stopped doing the show in 1983. I'd like to credit my partner artist Michael McClard who was series coproducer for the first two years until his one-man show at the Mary Boone Gallery In SoHo.

MI: I took it over in 1984 and 1985 then left for San Francisco in '86 to work for Francis Ford Coppola; Ronald Morgan, who plays the Reverend, was integral to the concept and development of the Peachy series and helped run the series - everything from designing schedules to delivering tapes to the cable station. Subsequent coordinators were writer/videomaker Terese Svoboda from '86 to '88 and finally videomaker Betsy Newman.

Still from "Crime Tales," 1982 by Robert Burden and Dictelio Cepeda

LB: Ironically, once the show was up and running the Kitchen (a premier video exhibition space) set up a Cable Viewing Lounge so that C-Update and other artists series could be watched by people who didn't have cable. Cable wiring was still very erratic in New York especially in poor neighborhoods. By the mid-'80s some of our programs were screened by museums such as MoMA, the Whitney and AMMI. Now artists' TV is part of the official history of video art.

Liza Béar is a writer and filmmaker based in New York and a Contributing editor at Bomb. Milly Iatrou is a filmmaker and sound editor. She lives in Los Angeles and New York. Details for the New Museum event are here: http://www.newmuseum.org/calendar/view/liza-bear-milly-iatrou-communications-update