In 1999, my senior year of high school, four of my friends were shot to death and another died in a car accident in front of my apartment complex. Personally, I was facing a DUI and three other charges and the possibility of jail time.

On the morning of my high school graduation in 1999, my mother took me on a six-week-long road trip that began in Virginia and ultimately culminated with our attending a Lakota Sundance in the Black Hills and later living with her friends on the Rosebud Indian Reservation.

All the stories of road trips I've come to love and admire over the years seem to depict young people who leave home hoping to loosen the collar of institutional confines; driving away from the path through life expected of them by loved ones; putting the well-ordered rhythms of consumption and work and family behind; fleeing the prospect of another four to ten years in school.

Driving through the Blue Ridge Mountains the first day of our trip, I knew it was not so simple. With the open country unfolding like a song, each new smoky blue-green vista a verse that lingered behind your eyes for miles and miles, I wondered whether I was running from something or toward something. I never imagined those first few days on the road that what I was about to experience in the Black Hills and Rosebud -- an encounter with the unsettled debts of America's past -- would forever shape my relationship with her future.

Up until that point, I knew very little about the realities of contemporary Native American life. There is, of course, great diversity among the more than 500 Native American tribes in the U.S. My particular experience, however, happened to be with my Mom's friends from the Rosebud Indian Reservation where the unemployment rate persists at nearly 70 percent and the life expectancy (together with the neighboring Pine Ridge Reservation) has been estimated at around 48 years old, the shortest life expectancy for any community in the Western Hemisphere outside Haiti.

I returned home from this trip burning with questions. How could our country celebrate the Lakota Sioux so frequently in romanticized accounts of the past without addressing the harsh realities of their present? What forces continue to nourish the roots of our historical amnesia? Above all, how was I going to play my part to ensure that, as Langston Hughes once wrote, "America will be?"

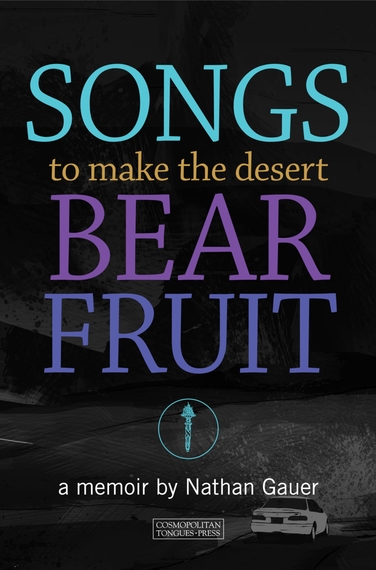

To say it plain, I caught a fire while out on the road in 1999. For the first time in my life, I awakened to a sense of purpose in my education. I began to believe that education was the greatest means of affecting lasting social change. In 2001, I went to study at Soka University of America and later earned my Masters in education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 2006. This fire also compelled me to stay up late at night for more than 15 years to work on my first book, Songs to Make the Desert Bear Fruit, which was published earlier this year by Cosmopolitan Tongues Press.

I sent a copy of my book and a letter explaining why I wrote it to President Obama about two months ago. In response, President Obama recently sent a card he and Michelle both personally signed and a nearly page-long message. In one particularly moving excerpt from this message, President Obama wrote as follows:

There is no denying some Americans have had the deck stacked against them, in many cases for generations. Native Americans face poverty rates far higher than the national average. In some places, it is nearly 60 percent. The dropout rate of Native American students is nearly twice the national rate. These numbers are a moral call to action. As long as I have the honor of serving as President, I will do everything I can to answer that call.

I was impressed by President Obama's clear-eyed viewed of American history. Even more impressive, however, is his perspective that the realities facing many people in the United States -- not least of which are our nation's original peoples -- "are a moral call to action."

I never could have guessed how my encounters with the people I met at the Sundance and on Rosebud would profoundly shape my relationship with her future. As I wrote in Songs to Make the Desert Bear Fruit about the morning I left Rosebud 15 years ago to return home, I imagine they were all...

... unaware how their voices would echo through the years, how their lives would travel. We turned reluctantly at the end of the street. Driving in silence, we passed a small clearing where a pole flying an upside-down American flag rose. I looked over my shoulder back toward Uncle Damien's and saw several thin tufts of smoke rising above Gabrielle and her daughter, past the thin, rotting roofs of the neighborhood, over the gently rolling hills and the young boys riding horseback and the makeshift crosses lining the worried roads, rising above and beyond this fierce, invisible struggle to survive and write new chapters in that unfinished epic, America.

Nathan Gauer enjoys interacting with his readers. Feel free to contact him at songsbearfruit@gmail.com or on Facebook.

To learn more about his new book Songs to Make the Desert Bear Fruit, visit http://www.songsbearfruit.com or find it on Amazon.

All illustrations in this post were created by Gonzalo Obelleiro and appear in Songs to Make the Desert Bear Fruit.