U.S. and Mexico Sign Agreement Guaranteeing Water for the Colorado River Delta, Sharing Shortages, and Facilitating Water Conservation Investments

by Michael Cohen and Peter Gleick

The Colorado River basin supplies drinking water to more than 35 million people in the United States and Mexico and irrigates more than 3.3 million acres in the two countries. The river, which flows through some of the most arid regions of the continent, has never been very large. Now it is so over-tapped that it usually dries up completely some 80 river miles north of its mouth atop the Gulf of California. The river's once-lush delta -- memorably described in Aldo Leopold's eloquent "Green Lagoons" -- has been tamed and tilled and converted to irrigated agriculture, or else lies desiccated and barren, deprived of the water and sediment the river once carried in abundance.

Where the Colorado River dies. Photo courtesy of Osvel Hinojosa-Huerta, 2012

That abundance is long gone.

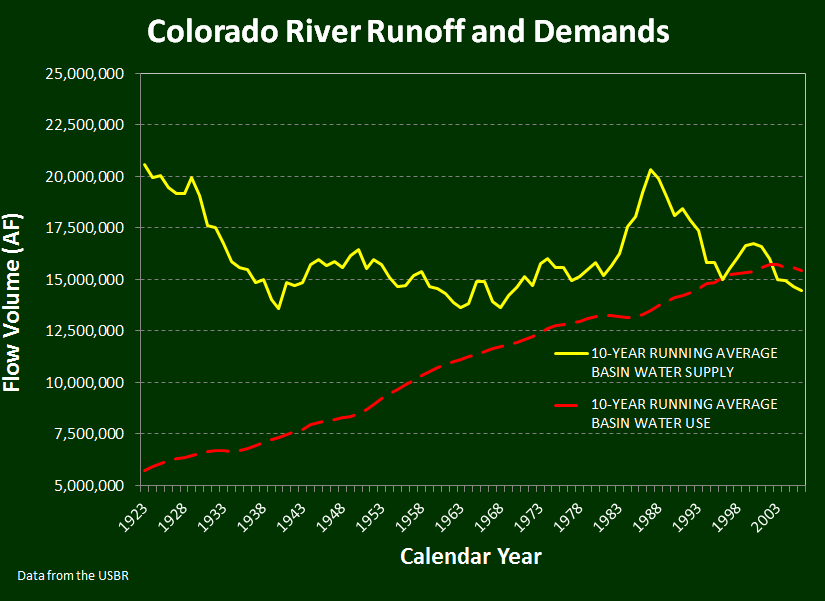

Even with a massive reservoir system that can store four times the river's average annual flow, demand for the Colorado River now exceeds its total renewable supply (see figure). To make matters worse, the Bureau of Reclamation's soon-to-be-released Colorado River Basin Study projects that climate change could further reduce total supply by nine percent or more in the coming decades, confirming research published over 20 years ago on the vulnerability of the river to climate change. Within the next several years, Arizona and Nevada will likely see their total take of the river reduced as the falling elevation of Lake Mead triggers shortage declarations; a decade-long drought and low runoff in the upper basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming means that many have already seen supply fall well below demand.

But it is the Colorado's already-stressed delta that bears the brunt of the excessive demands on the river. Some hardy cottonwoods and willow trees still cling tenaciously to the river's banks, especially at the uppermost extent of the remnant delta, just below Morelos Dam (near Yuma, Arizona). The likelihood of an even drier future meant that these few remaining vestiges of a once-rich ecosystem faced a very grim future.

Earlier this afternoon, their prospects improved dramatically.

At the historic Hotel del Coronado in San Diego, the U.S. and Mexican commissioners of the IBWC -- the binational agency that manages water crossing the border -- signed Minute 319, an amendment to the 1944 treaty that allocates Colorado River water between the U.S. and Mexico. U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar and Mexico's Ambassador to the United States Arturo Sarukhan also attended the signing ceremony, highlighting the importance of this new agreement to both countries.

Minute 319 brings material benefits to water users on both sides of the border. It guarantees that, for the first time ever, some water will regularly flow in the usually-dry Colorado River channel below Morelos Dam. The landmark agreement enables Mexico to store Colorado River water in the U.S., in Lake Mead, providing Mexico with reliable surface storage and a buffer against future shortages. Minute 319 creates a mechanism for U.S. water agencies to invest in improving the efficiency of Mexico's Colorado River canals, improving long-term reliability and on-farm deliveries for Mexico and generating short-term additional water for the U.S. investors. For the first time, Minute 319 sets clear criteria for reduced deliveries to Mexico in times of shortage, averting a potential diplomatic standoff while adding certainty and predictability to water managers' planning efforts. The agreement also establishes a strong foundation for future collaboration.

Nothing happens quickly in Colorado River law; this new agreement is no exception. Reflecting U.S. river users' discomfort with major change, the agreement is also temporary; in effect for only five years (almost exactly as long as it's been since the domestic shortage agreement was signed). Minute 319 is the product of more than three years of intense binational negotiations, hampered by a language barrier and very different approaches to river management. On the U.S. side, the seven basin states, and especially Arizona, California, and Nevada, were very active participants: a great deal of the credit for reaching agreement goes to Michael Connor, Reclamation's Commissioner. On the Mexican side, negotiations required a similar display of courage and commitment to see through major changes in river administration. Several small-scale habitat restoration projects in the delta, managed by non-profits such as ProNatura Noroeste, further bolstered the negotiations by demonstrating how much can be achieved when surface water is available.

The foundation of the current agreement, however, goes back much more than three years. Twenty years ago, scholars in Mexico and the U.S. began to publish articles about the endangered wetlands of the Colorado River delta. The Pacific Institute issued a report in 1996 saying "Some minimum amount of water must be allocated and guaranteed to restore at least part of the formerly rich Colorado River delta." Subsequent reports and conferences and litigation eventually led to Minute 306 in December 2000, and a binational commitment to start to work on delta restoration. This led directly to a binational conference on the delta that started on the tragic date of 9/11/01. Subsequent changes in binational relations, including the unilateral decision to line the All American Canal without official consultation with Mexico, did inestimable harm to cross-border cooperation and trust.

The negotiations that led to Minute 319, and especially the leadership shown by officials on both sides of the border and the commitment of time and energy by environmental research and advocacy groups, went a long way to heal and improve binational relations. Water managers toured facilities in each other's countries, learning about their neighbor's practices and concerns, exchanging information, building relationships.

After more than 15 years of research and advocacy to get water back in the river, this remarkable achievement is a huge step forward for the embattled Colorado River delta. It is incredibly satisfying to think that the dedicated efforts of so many people, over so many years, have led to this historic moment. It is a long overdue end to the incredibly destructive 20th Century notion that not a drop should be left instream and it is a major step to more sustainable management of the Colorado River -- the lifeblood of the Southwest.