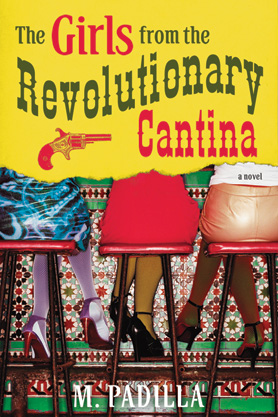

Mike Padilla's debut novel, The Girls from the Revolutionary Cantina, tells the story of a group of Mexican American women in the San Fernando Valley trying to cope with career pressures and romantic relationships while maintaining lifelong friendships. A heartfelt comedy, Padilla blends humor, sex and clever plot twists to deliver a novel that entertains while saying something thoughtful about the modern Latina experience in Southern California.

Mike Padilla's debut novel, The Girls from the Revolutionary Cantina, tells the story of a group of Mexican American women in the San Fernando Valley trying to cope with career pressures and romantic relationships while maintaining lifelong friendships. A heartfelt comedy, Padilla blends humor, sex and clever plot twists to deliver a novel that entertains while saying something thoughtful about the modern Latina experience in Southern California.

I caught up with Mike after a book signing in San Francisco and he was gracious enough to answer a few questions about Cantina and his writing career.

MC: Some reviewers are calling Cantina a Latina Sex and the City. Do you think that's an apt comparison?

MP: Sex and the City, the TV series, and Cantina are both about a group of career-minded women facing relationship challenges in an urban setting. On that level, I appreciate the comparison. However, I think where Cantina diverges significantly is in the source of the dramatic tensions that drive the narrative. In Sex and the City, the four friends almost without exception never experience significant conflict among themselves. They experience conflict outside their largely idealized friendships, then reconvene for support, advice and cocktails.

With Cantina , I was much more drawn toward exploring the forces that cause friendships to begin, evolve and sometimes die. The conflicting needs and desires that arise as people grow and change interest me much more than friendships where everyone gets along and is perfectly supportive. It's also a rich source of comedy. I don't think Cantina would be nearly as funny were it not for that kind of conflict.

MC: You grew up in Northern California, but set the book in Southern California, where you now live. Is there a difference between the Chicano experience in the North and the South? Could you have put the book in Northern California?

MP: There is a cultural vibrancy that I love about Southern California, a kind of wonderful madness to daily life that I think fits well with the zany scenarios I had in mind for my characters. The range of Chicano experience here, from new arrivals to culturally-assimilated Chicanos, exists in the north as well. But here it feels more pronounced to me, perhaps because of Los Angeles' proximity to Tijuana. I wanted Cantina to reflect that range. I also wanted to touch on the culture of celebrity, which I find so fascinating. Los Angeles was a natural setting for the story.

MC: You studied with Tobias Wolff in the Syracuse Creative Writing MFA program. Has he had an influence on your work? How would you characterize it?

MP: He was an incredibly accessible mentor, a warm person who took writing seriously but didn't take himself too seriously. What has stayed with me more than any of his writing advice is the thoughtfulness and respect with which he treated both his characters and the people around him.

MC: What's your opinion on the raging debate over the value of writing MFAs -- particularly the argument that university creative writing programs churn out bland, derivative writers?

MP: That same argument was around when was at Syracuse in the '80s -- that there is more bad writing being published today and MFA programs are to blame. I don't buy it. There was just as much bad writing floating around before writing programs existed. I also don't buy the related notion that MFA programs live in fear of making bold choices in the students they admit because they're scared of anything controversial. These writer-instructors have to scour through tons of very bad manuscripts to find just a few gems. Is the process somewhat subjective? Yes. Are they suppressing dozens of brilliant manuscripts for fear of rocking the establishment? I seriously doubt it. These are people who live for good writing. If they see something controversial or even upsetting, they're going to jump on it -- if it's compelling storytelling.

Even if all MFA writing programs do is introduce to the world writers who can capture the imagination for a few hundred pages at a time -- or who go on to non-writing careers where they impart their love of words to others -- that's a net benefit for society.

MC: Did you originally conceive of the book with the plot as written, or did it change in the writing?

MP: Writing Cantina was an exercise in not knowing where the story was going. Unlike some other writers, I've never been able to foresee entire plot trajectories. My stories rarely go as planned, which I find more interesting than when they do. For instance, when I started Cantina, my intention was to write a drama about a woman facing career challenges unique to the modern Latina. However, as I wrote, Julia's friends began doing and saying funnier and funnier things. They began to dominate her world. A new kind of story, a comedy about friendship, emerged.

MC: You do an excellent job of balancing humor, pathos and suspense in the book. Did you find that challenging, or did your conception of the characters and the plot make it easy to avoid, for example, introducing humor into scenes where it would be inappropriate?

MP: I tend to rely on a combination of instinct and having smart readers critique my work to achieve that kind of balance. With Cantina, there were plenty of times where people said, "This is the wrong place to be funny" or "Why aren't we feeling Julia's loss here?" Sometimes my instincts are good, but sometimes I need someone to wag a finger when I get something wrong.

MC: You explore a lot of different themes in the book -- sexual orientation, the experience of early generation immigrants versus later generation, and women in the workplace to name a few. In your mind, is there an underlying theme in the book that explains or motivates the plot?

MP: The theme that for me threads these other elements is Julia's the need for emotional and financial security. She desperately wants to feel secure, so she creates safety nets in the form of friends and work. It's what drives her story. When her safety nets fail, she has to ask: is there a more fundamental way to achieve a sense of security in the world?

MC: What's the thing that's surprised you most about the reception of the book?

MP: When people say they lost sleep because they stayed up to find out how the book ends.

MC: Although you've published short stories -- in magazines and in a collection, Hard Language -- this is your first novel. Could you have written it earlier in your career, or was the work you did in short fiction an important prerequisite in some way?

MC: Although you've published short stories -- in magazines and in a collection, Hard Language -- this is your first novel. Could you have written it earlier in your career, or was the work you did in short fiction an important prerequisite in some way?

MP: I think I would have felt overwhelmed had I tried to write a novel without having written short stories first. I wouldn't have had the confidence. Having said that, I had to learn different skills for each form. Short stories required learning patience for crafting and re-crafting the story to get it right. For the novel I also had to learn how to suspend my desire for control and accept that I wasn't going to know how things ended until I got to the end.

MC: What's next for you?

MP: My current project is a novel about a Latino family struggling to get ahead against the backdrop of the last two years of the Vietnam War. The protagonist is a 16-year-old who has to run the family business after his father hurts himself, and about the conflict that ensues when the father returns to work with very different ideas about how things should be done. It's a drama. There's humor in it, too, but of a different variety than Cantina. Even in the darkest stories, it helps to maintain a sense of humor.