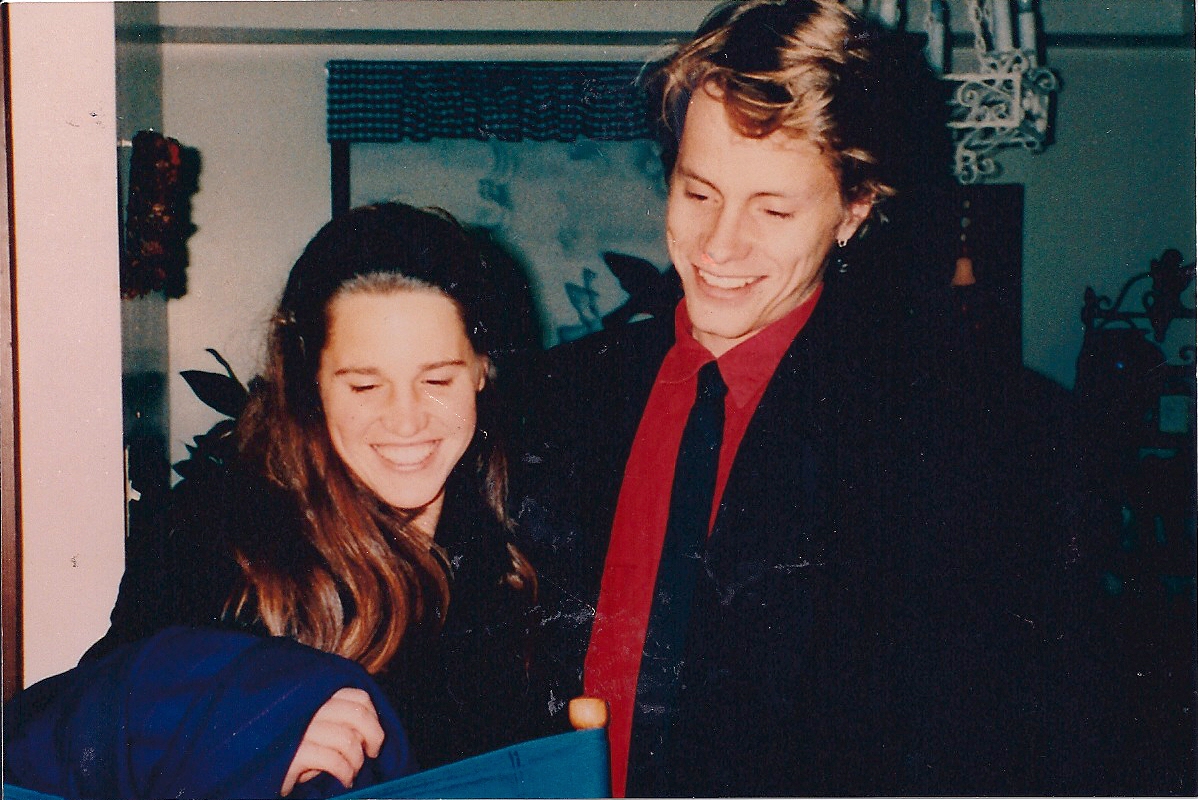

I met Dr. Stulbarg when I was 22, and had just moved to San Francisco to be with my boyfriend Stephen. Stephen had cystic fibrosis, but he'd been unusually healthy as long as I'd known him. Then, three weeks after my arrival, on a Saturday night, his lung collapsed while we were driving to a party. Stephen was casual, I was terrified, and this began the part of our relationship for which there was no map.

Things seemed simple enough at first. We drove to the hospital; Stephen got a chest tube, and his lung healed. But the day he was supposed to come home, his lung collapsed a second time. We sat squeezed together on his hospital bed, drinking our morning coffee, talking with Dr. Stulbarg about what would happen next.

Stephen had told me about Dr. Stulbarg already. Stephen loved that he was direct, crisply funny, and had been a philosophy major in college. He never pretended that medicine had all the answers, but he was deeply engaged in the mystery. In this moment, I wished Dr. Stulbarg would at least pretend to have all the answers. Instead, he described a procedure called pleurodesis. It involved injecting the lung with tetracycline to irritate it until it scarred and stuck to the chest wall. I winced. The results sounded promising, the method prehistoric. "Sounds painful," I murmured.

"Very painful," Dr. Stulbarg said, and I felt my own affection for him, for the way he didn't shrink from the question, but also didn't shrink from his proposal. And for what he said next. Stephen would be sedated, but his body would go through the motions. "I don't want you anywhere near this room," Dr. Stulbarg said to me.

This would be the first of many times that Dr. Stulbarg looked out for me. I don't think it was because he had a special fondness for me, or for Stephen. I think he understood that Stephen's health was linked to mine, that since Stephen would rely on me, he'd be wise to pay attention to both of us. Though this is important for any couple in which one person suffers a serious illness, we may have been especially in need. We were young -- 22 during that first visit, and 25 when we got married -- and we had no idea how long Stephen would live.

This is where Dr. Stulbarg did his best work. During appointments, he and Stephen talked about how to make decisions given the absence of years ahead. He was not only comfortable with mortality, but with the more stigmatized outgrowths of chronic illness -- depression, and dependency. He helped Stephen live longer, but maybe more importantly, he helped him live fully in the time that he had.

Looking back, I think a lot about how Dr. Stulbarg was able to provide the kind of care he offered. Yes, he may simply have been an excellent doctor, but what conditions help the best doctors thrive? The care he gave Stephen took place fifteen years ago. I wonder if he could have found time for those conversations now, had he been required to do 10 minutes of paperwork for every appointment, squeeze four patients into an hour, or frequently check his computer screen.

The care he provided was also possible because of the way we conceived of doctors as a culture. Stephen was a patient at an interesting crossroads in doctor-patient relations. We were making the transition away from the Marcus Welby-type role -- the doctor as all knowing, to the doctor as facilitator. Patients had begun to take charge of their health, but they hadn't yet been portrayed by the insurance industry as consumers.

I have no problem with the consumer concept when it comes to buying insurance, assessing costs of hospital services, or comparing options for care. But I think it's a bit ominous when applied to the medical care itself. When a patient is simply a consumer, a doctor is simply a service provider, interchangeable with any other service provider. That might be convenient for an insurance company, or a managed care group, but it's dissatisfying for the rest of us. Gone is the relationship. And without the relationship, in my eyes, true quality care disappears.

We all have stories of the teacher who changed our lives. If you spend enough time in the landscape of serious illness, and you're lucky, you have that story about a doctor. Here's mine. When Stephen was 30, almost two years after his double-lung transplant, he got a serious infection in his lungs. He went into the hospital, and the next morning, he was put on a ventilator. For two weeks, the doctors and nurses in the ICC worked around the clock.

One evening, Dr. Stulbarg came into Stephen's room, and asked me if I had a minute. We sat in his office, in the dim light of dusk.

"I know you guys," he said, "and I know you'd want to know."

The odds that Stephen would live were very slim. Dr. Stulbarg held my hand, and in spite of myself, the tears streamed down my face. I was 29, and at that moment, if I could have traded 10 years of my future for another month with Stephen, I probably would have done it. Luckily for my future self, I couldn't, I just sat in that chair, winding my feet around its legs. I asked Dr. Stulbarg how long he thought Stephen had. Days, he told me, probably a few days.

"You can think about how you want this to go," he said.

And I thought. I tried to do what Dr. Stulbarg had encouraged us to do all along -- to figure out what we could do with what we had. I told him I wanted the chance to talk with Stephen one more time, and I wanted to sleep with him in his bed on his last night. He made sure those things happened.

How differently Stephen's death would have gone without that conversation -- if Dr. Stulbarg hadn't known me well enough to know I'd want to know. It sounds dramatic, but sometimes I think I might not be the same person, or at least I wouldn't have the same relationship to death, and to Stephen's passing. I was able to be with him fully in those last days. How can you measure the value of that? It has made me a happier, healthier person. It was a gift I can never repay.

Elizabeth Scarboro's memoir My Foreign Cities, about her marriage to her first husband who had cystic fibrosis, was released in paperback this February from the Norton imprint Liveright. Her essays have appeared most recently in The Millions, The New York Times, and The Bellevue Literary Review. Visit her website: elizabethscarboro.com.

A version of this post was originally published in October, 2013, at Kevin MD.