I've got a book in front of me: According to the cover, it's the "20th Anniversary Edition of the Classic Bestseller." The book is called And The Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic.

It was written by Randy Shilts, who in the book's acknowledgments states, "I would not have been able to write this book if I had not been a reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle, the only daily newspaper in the United States that did not need a movie star to come down with AIDS before it considered the epidemic a legitimate news story deserving thorough coverage."

It's a striking statement, isn't it, with the benefit of hindsight? What Shilts in 1987 described an epidemic we now know to be a pandemic, a global massacre by infectious disease. According to AIDS.gov, 36.9 million people currently live with HIV/AIDS and, "Even today, despite advances in our scientific understanding of HIV and its prevention and treatment as well as years of significant effort by the global health community and leading government and civil society organizations, most people living with HIV or at risk for HIV do not have access to prevention, care, and treatment, and there is still no cure." Thirty-four million people have died from AIDS to date.

Shilts understood what others did not because, as a reporter in San Francisco, he saw the devastation in a way most didn't. He also acquired HIV himself. His health crisis and the roadblocks that the medical community put before him as a result motivated him to investigate.

A couple of important selections from Shilts's prologue:

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome had seemed a comfortably distant threat to most of those who had heard of it before, the misfortune of people who fit into rather distinct classes of outcasts and social pariahs. But suddenly, in the summer of 1985, when a movie star was diagnosed with the disease and the newspapers couldn't stop talking about it, the AIDS epidemic suddenly became palpable and the threat loomed everywhere.

Eventually, Shilts wrote, "there was a threat to the nation's public health that could no longer be ignored." But:

By the time America paid attention to the disease, it was too late to do anything about it. The virus was already a pandemic in the nation, having spread to every corner of the North American continent. The AIDS epidemic, of course, did not arise full grown from the biological landscape; the problem had been festering throughout the decade. There had been a time when much of this suffering could have been prevented, but by 1985 that time had passed. Indeed, by the time we learned that Rock Hudson was stricken ... hundreds of thousands were infected with the virus that causes the disease.

It's late May. May is Lyme Disease Awareness Month. Unlike World AIDS Day, which even Google has indexed on its calendar, and likewise unlike Breast Cancer Awareness Month, Lyme disease awareness activities don't get much publicity. A lot of people work hard to raise awareness, but sadly it's mostly among themselves -- as was the case before Randy Shilts began to publicly document the HIV/AIDS crisis and, more significantly even in Shilts's admission, before celebrities began to contract HIV or act out in support of AIDS patients. Elizabeth Taylor alone fast-forwarded recognition of the reality of HIV/AIDS by years and saved countless lives in doing so.

I don't know how to make this plainer: Lyme disease is the AIDS of our time. We are, right now, where Randy Shilts was when he wrote And the Band Played On. Yet only 30 years later, the public still can't see what's right in front of them. Health Scares of the Week, from Ebola to West Nile to SARS to bird flu to swine flu come and go and thus far have affected few Americans; meanwhile, one in every 100 Americans each year contracts Lyme, and many of them develop multiple sclerosis-like conditions following prescribed treatment. Patients are desperate, many going bankrupt trying to find help for their disabling condition. They are met with silence. Sometimes even with laughs.

The very title of Shilts's book refers to the obliviousness and disinterest of, well, everyone when the AIDS crisis was emerging -- there was an explosion of illness. The band played on, undisturbed and uninterrupted.

The band is playing on now, as I write this.

The CDC estimates that over 300,000 Americans are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year. The CDC unfortunately also insists that Lyme can be easily diagnosed and easily cured, permanently. So strange for a public health crisis of the sheer magnitude of Lyme disease, relatively little -- $24 million per year -- is invested in researching the disease pathology, diagnostic tests, and treatment.

As with AIDS and Rock Hudson, respectful Lyme disease stories have made the news most often when a celebrity who has Lyme was involved. Avril Lavigne was put on the cover of PEOPLE, and she told NBC's Today that, "This is what they do to a lot of people that have Lyme disease. They don't have an answer for them, so they tell them ... 'You're crazy.'"

- Double vision for longer than one week, in consecutive days with no break.

- Paralysis of a limb for longer than one week, in consecutive days with no break.

- Incontinence. That is, losing all control of my bowels.

Otherwise, it was essentially, "We tried. We looked. We have no idea. Try to take your mind off of it because, unfortunately, that's all that can be done at this time." I appreciated the honesty, frankly.

And I was surprised and disappointed to discover that so many medical doctors today are one hundred percent dependent on existing laboratory tests to determine whether or not anything is wrong. Even if a patient is falling apart, in excruciating pain, even with paralysis, most doctor do not investigate once labs come back inconclusive. In my mind, this lack of medical investigation is a perfect recipe for cultivating a new epidemic such as HIV/AIDS. We now know that AIDS victims may not be symptomatic for 10-15 years, and during its incubation period, those infected can unwittingly transmit it to countless people. Within a decade, the contagion is exponential before anyone even knows the disease exists. This happened prior to the known emergence of the AIDS crisis and the HIV virus in the 80s, and it is bound to happen again if medical professionals refuse to investigate prevalent, consistently presenting medical issues about which not much is known.

Ally Hilfiger, daughter of designer Tommy Hilfiger, has been making the rounds with Bite Me: How Lyme Disease Made Me Crazy, Stole My Childhood, and Almost Killed Me, a memoir of her disastrous young life with Lyme disease. She told New York magazine: "I sat down at my computer and decided one day. I said, 'Listen, enough is enough, I'm going to sit down and write this.' And I started writing. There was something outside of me that was propelling me. It was my duty, and I did it," she added.

Hilfiger said about another prominent case of Lyme, that of Yolanda Hadid (formerly Foster), a star of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills whose devastating illness has been dismissed as a mental illness such as Munchausen's by proxy, "It's very sad what they're going through, the Hadids, because nobody should ever be questioned about a disease that they're going through, or what they're telling people that they're feeling ... Nobody should question a disease."

And yet they do. I don't have the space to go into it here, but in an important series of articles called "Deconstructing Lyme Disease -- Room for Debate" (from 2013, and in desperate need of an updated take based on newer science), The New York Times discusses the Lyme disease controversy from multiple perspectives. This includes, of course, a high-profile person -- Amy Tan, author of The Joy Luck Club, who describes a horrific Lyme experience that closely reflects my own. She wrote:

Many members of the medical establishment who dictate the official criteria for Lyme diagnosis, treatment and insurance coverage still maintain that Lyme is easy to diagnose. They discount research that shows Lyme bacteria can evade detection by standard blood tests. And they play down late-stage cases like mine, which require intensive, long-term treatment, insisting the disease is always cured with a simple round of antibiotics.

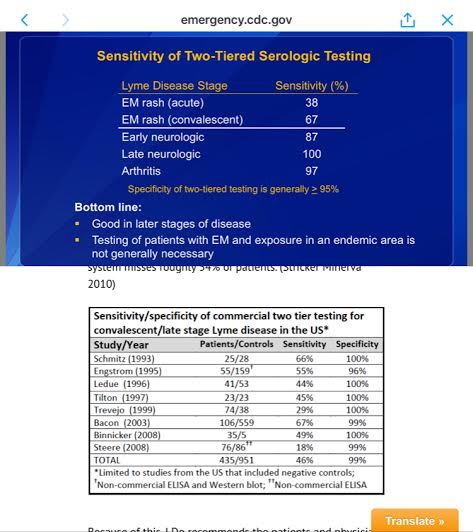

Above, top: A slide used by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during a May 24, 2016 conference call for medical professionals about Lyme disease, stating that the CDC-recommended Lyme disease blood tests are 100 percent sensitive in late-stage Lyme disease. Above, bottom: 8 discrete studies published in peer-reviewed journals concluding that these tests are 18 to 67 percent sensitive. CDC did not cite sources for its 100 percent sensitivity claim, and did not respond to a request for citation.

This is reality. There is a Lyme Disease Awareness Month because the band keeps playing on. We all know that celebrities and well-respected known people have access to special treatment -- yet in this truly inexplicable trend, even they are told, when they present with devastating health issues, that they are not ill -- Avril Lavigne was lazy, Ally Hilfiger was crazy, Yolanda Hadid has Munchausen by proxy, Amy Tan was told that Lyme is rare and while something may be wrong--something that can't be diagnosed -- it is not Lyme. I was told the same. She started antibiotic treatment and her health improved. So did mine. So did Ally Hilfiger's, so did Avril Lavigne's. If you knew someone to whom this was happening, it would blow your mind. Well, brace yourself, because based upon the sheer prevalence of Lyme, the third most common infectious disease in the country and the fastest-spreading bacterial disease, you'll know someone soon if you don't already. And you will wish that someone had done more about it before it happened to that person, who could be you or your child. While we fondly reminisce about those SARS and swine flu scares, Lyme disease is approaching from the horizon like a tsunami -- a tsunami coming at us from all sides.

The band plays on while countless people go through this same ordeal. Those I mentioned are only a few of the high-profile people who went through this. There's your celebrity. Pay attention. And then there's little old me -- not known to anyone, but screaming out into the world for people to connect the dots because the downplaying of the emerging AIDS virus of the 80s and the emergence of Lyme and associated tickborne infectious diseases.

The band plays on. Randy Shilts wrote that by the time the public caught on to the prevalence and severity of HIV/AIDS, it was "too late." I hate to say this, but the same is true of Lyme. Except that, as we saw with HIV/AIDS, it's not too late to invest in research. It's not too late to develop diagnostic tests that work. It's not too late to support researchers so that they can figure out how this bizarre, misunderstood and miscommunicated disease works and then find a way to manage or cure it.

Silencing conversations about epidemics is extraordinarily dangerous. Yet that is what is happening right now. A reporter from a Salisbury, Maryland news station asked the Centers for Disease Control and prevention to speak with her about Lyme disease, given that it is Lyme Disease Awareness Month. She was told:

At this time, we respectfully decline your request for an on camera interview.

She posted the correspondence on the WMDT47/ABC News website, and it's telling of the way this disease is being handled. Over 300,000 cases per year, dismissed as insignificant and warranting $24 million in NIH funding, in favor of Zika's emergency status (like SARS, swine and bird flus, Ebola), which is the top priority at CDC and to which Congress is considering dedicating $622 million to $1.1 billion in response to the White House's request for $1.9 billion.

CDC Director Tom Friedman was quoted in the New York Times as saying: "Three months is an eternity for control of an outbreak," he said, adding: "There is a narrow window of opportunity here and it's closing. Every day that passes makes it harder to stop Zika."

"This is no way to fight an epidemic," Friedman said.

To date, Zika has affected 544 Americans, not one of whom contracted it domestically.

Annually, over 300,000 Americans contract Lyme disease in this country. Think about those numbers. You can count to 544. Try counting to 300,000.

Denying funding, refusing to revise medical guidelines that are not working, denying media interviews about Lyme disease... This is no way to fight an epidemic, I say.

I have to tell you, thinking and talking about Lyme disease brings tears to my eyes. Not only because of the terror it has brought to my life. Not only because I've now met hundreds of people who are going through similar stories. Not only because, despite so many high-profile cases making the news as blips that come and then are forgotten. But because this has happened before, and histories like this should not repeat.

From And the Band Played On:

Because of their efforts, the story of politics, people, and the AIDS epidemic is, ultimately, a tale of courage as well as cowardice, compassion as well as bigotry, inspiration as well as venality, and redemption as well as despair.

It is a tale that bears telling, so that it will never happen again, to any people, anywhere.

Shilts wrote this in 1987. He died from AIDS in 1994.